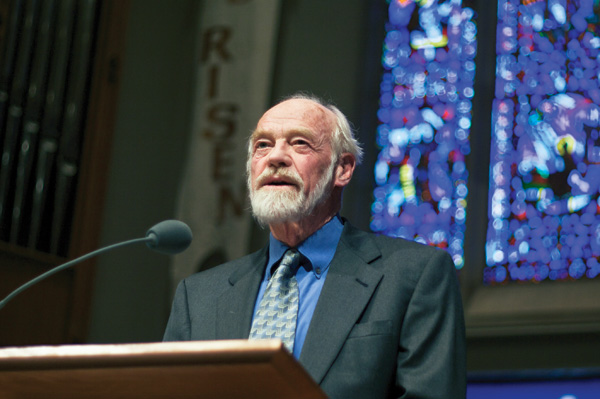

He's a Christian who didn't like pastors, a seminarian who wasn't interested in pastoring, a pastor who segued into a writer, a writer who was criticized for creating a paraphrase version of the Bible and a scholar who thinks theology is ruined by theologians. Eugene Peterson, author of the popular The Message paraphrase of the Bible, has pursued his unusual walk with God as a “haphazard dog following a scent.” In person, he is an unassuming elder—tall, balding and bearded—who can't stop flashing a wide gentle smile. When you ask him a question, he'll pause, contemplate his response and then deliver his thoughts in a low, amiable tone.

He's a Christian who didn't like pastors, a seminarian who wasn't interested in pastoring, a pastor who segued into a writer, a writer who was criticized for creating a paraphrase version of the Bible and a scholar who thinks theology is ruined by theologians. Eugene Peterson, author of the popular The Message paraphrase of the Bible, has pursued his unusual walk with God as a “haphazard dog following a scent.” In person, he is an unassuming elder—tall, balding and bearded—who can't stop flashing a wide gentle smile. When you ask him a question, he'll pause, contemplate his response and then deliver his thoughts in a low, amiable tone.

“We are in the middle of chaos, to tell you the truth,” he says, when asked about the current state of the Church. “But we always have been. We have to be very careful that we don't embrace the chaos or find fragments of the chaos that we like and specialize in. We really are working in a wasteland. We're trying to find our way through prayer, awareness and attentiveness to the Word made flesh.”

Then he reveals a personal hero, a man he calls “the patron saint of pastors.”

“That's why the Revelation of John became a really important work to me early in my pastorate,” he says. “Here is a man living in chaos—recreating the whole scriptural vision as a poem that made sense of it all. He was living in the worst of times, but there isn't a pessimistic line in the book—it is all about prayer and worship.”

There's great irony in this observation because Peterson didn't hold much respect for pastors when he was growing up.

Called to Minister

“Pastors always seemed to be marginal to the business of living,” Peterson remembers. “I didn't take them seriously. Mostly I liked them, but I rarely respected them.”

Perhaps that was because they only stayed a few years at his home church before moving on. “None seemed particularly interested in God,” he says, “And I was getting interested in God.”

This underlying interest in God led him to attend the New York Theological Seminary. There he immersed himself in studying the Bible before doing graduate work in Semitic studies, getting married and serving as an associate pastor in nearby White Plains. In the meantime, he taught a variety of courses at the seminary, filling in for professors who were on sabbatical.

That's why he was shocked when he realized he wasn't called to be a professor, but a pastor. “The classroom was too tidy,” he says. “I was beginning to think it was too easy.” This late calling was reinforced by his wife, Jan, who had prayed to be a pastor's wife, but had set it aside to marry him.

“I didn't think I was going to be a pastor until I was 27 years old. I was going to be a lay person. So I was trying to read the Bible not as a preacher, as a scholar, as a professor, but as a Christian,” he admits, while discussing his favourite Bible character—David. “Here is David who gets more space than anybody else in the Bible and he is a lay person and he didn't do a very good job of it.”

“You have somebody who is placed right at the centre of the Bible, of whom Jesus is called the son of David, so he was making a strong connection there. You are not given a picture of somebody who's got it all right; he messed up a lot. He prayed a lot; not because he was good at praying, but because he was in trouble most of the time. He lived in a lot of chaos. I was working with people who were living in a lot of chaos.”

The Hidden Truth

The Petersons started a church in the basement of their home outside of Baltimore; a parishioner then nicknamed it Catacombs Presbyterian Church. “It was exhilarating work,” Peterson says, glowing.

Unlike many pastors, he didn't do a good job of reading his sermons from the pulpit. After a few years of effort, he gave up, realizing, “this isn't me.” From that point on, he only used notes when preaching. After three years, they constructed their first church building on a hill. When they left, after 29 years of pastoring, Christ Our King Presbyterian Church averaged 500 regulars.

“As pastors, we live in a world far worse than the gang world or the criminal world,” he notes. “Most of the sin that we are working with is either hidden or subtle. People's righteousness often has a veneer. You can get by with anything if you are good enough. You can be hypocritical if you are skilled enough.”

While pastoring, he had no time for the contemporary “church-as-business” model that became so popular for so long, emphasizing flow charts and marketing to reach the lost. “It might be the modern way, but it wasn't the Jesus way,” he says. “It struck me as a terrible desecration. We're now in charge of the Church. It's no longer God; it's us. So there's this tension. We want to stay sinners.”

In spite of our self-centred tendencies, Peterson trusts God's greater plan. “I really believe this is Christ's Church, flaws and all. Sins and all. He could have created the perfect Church.” Smiling, he adds, “The Holy Spirit doesn't seem to mind being embarrassed.”

Communicating the Word

When he was retiring from his pastorate, an editor asked him to translate 10 chapters of Matthew as a test run for The Message. Peterson was disappointed with his efforts until he decided to write it as if for his parishioners. “I just tried to translate them into the language of the people I was living with,” he revealed. His completed work eventually won a Gold Medallion Book Award and has remained a bestseller since it was released in 2002.

Because The Message is a contemporary paraphrase of Scripture, instead of a straight translation, he received heavy criticism from fellow Christians, as if his methods proved he didn't believe Scripture. But Peterson took great pains to be faithful to the text.

“I believe everything is true,” he says. “I believe it takes paying attention to, respecting, honouring, giving reverence to the Word. But when you start to read it, you have to read it prayerfully in a listening way.”

He's recently published the fifth and final book in his Conversation series—“the primary language of spiritual maturity is conversation; when you're in conversation you listen a lot”—and has completed a memoir that is slated to be published in the fall.

Although he's focused on writing, Peterson still takes time to connect with people. “I receive a lot of guests. I write letters to people who write to me. And I am a pastor, so if someone stops me on the street and says, 'Let me tell you my problem or what's going on in my life,' I listen to them. It's pastor work, although maybe that's too fancy of a word. I'd call it friendship work.”

In recent years, he's also become reacquainted with The Salvation Army. “In the area where I live, the Army has an extensive social ministry and we've been a part of that appreciatively,” he says. “The Salvation Army is a disciplined, compassionate ministry. It's a creative and inventive way to deal with the world around us.”

For Peterson, serving suffering humanity is another way of living our theology in the contemporary world. And it reminds us that everything we have is a gift from God.

“We need to change our orientation from demanding something to receiving something,” concludes Peterson. “For the most part, God doesn't act like we think he ought to.”

Selected Bibliography

• The Message: The Bible in Contemporary Language

• Eat This Book: A Conversation in the Art of Spiritual Reading

• The Wisdom of Each Other: A Conversation Between Spiritual Friends

• Living the Resurrection: The Risen Christ in Everyday Life

Leave a Comment