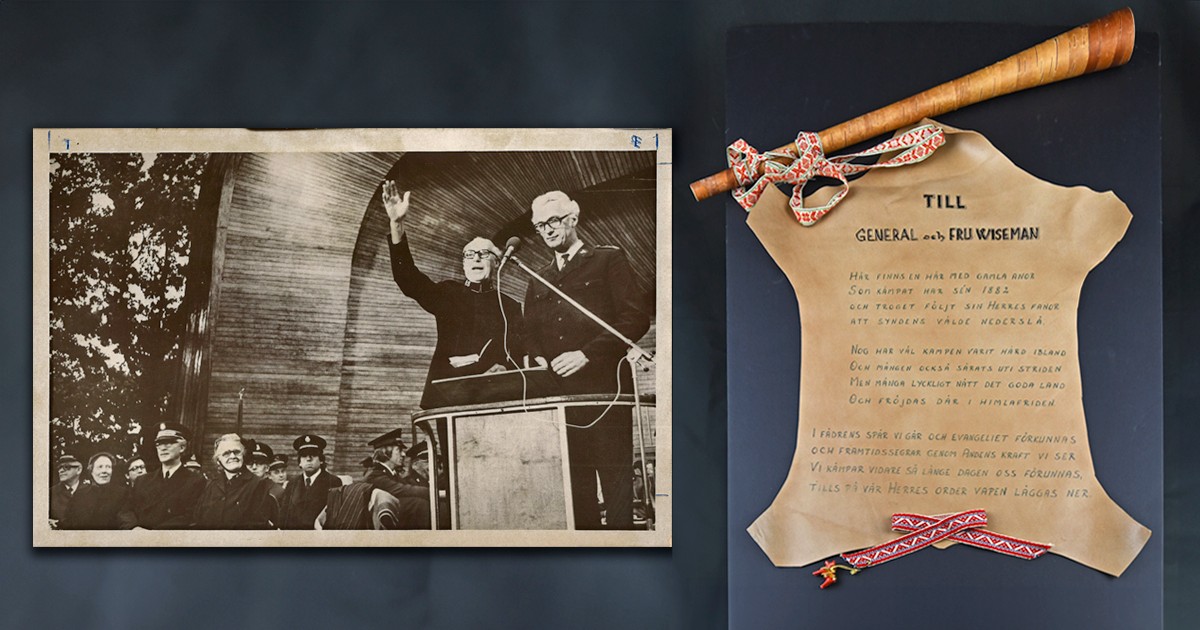

Returning to Our Roots

Is The Salvation Army still a church for the streets?

by Lieutenant Mirna Dirani Opinion & Critical ThoughtThe Salvation Army was founded to serve both worlds—body and soul—but over time, they can feel disconnected. Our corps can become consumed with maintaining programs, buildings and schedules. At the same time, our social service ministries often carry the load of engaging the community. If William Booth walked into one of our corps today, what would he see?