Seven years ago, when we began an addictions day-treatment program at The Salvation Army’s Addictions and Rehabilitation Centre in Victoria, we didn’t have a lot of money. We had one addictions counsellor whose top priority was to help the men see themselves differently, stemming from our belief that most people’s destructive behaviour is not the result of simple choices, but rather the consequence of injured lives and distorted perspectives.

At the beginning and end of the 12-week program, the men were given a poster-sized sheet of paper and asked to answer, “Who am I?” At our first graduation ceremony, they read both aloud. The “before” posters usually had a few short statements, such as “I’m an addict” or “I am unemployed,” written so small it was hard for the audience to see. The “after” posters, on the other hand, were filled with expressive and optimistic sentences, such as “I am a child of God,” “I am fearless” and “I am patient with my shortcomings,” written in large letters.

Each man’s testimony shared similar themes. Each one had encountered abuse or trauma, often in early childhood. To provide relief or escape, they turned to alcohol or drugs. Following this were many years of battling addiction. The testimonies concluded with hope that this time around things would be better.

Many of the graduates went on to successfully reintegrate into society. In seeing themselves differently, they approached the world differently. That was an important lesson for me.

Another lesson was more personal. I had to admit to myself—and asked the audience members at the graduation to admit as well—that perhaps the only reason we weren’t in the same situation as these men was because we had a larger degree of social advantage. I wasn’t physically or sexually abused; I didn’t grow up in abject poverty and shame; I didn’t suffer emotional and psychological torment from the people who were supposed to love me. Where would I be if I had? I can only imagine.

Christian social justice means ensuring that every person is given the opportunity to realize their God-given potential. But we must first acknowledge that not everyone coming to us for help began their journey at the same place.

Telling a homeless person that he can stay in our shelter for 20 days like everyone else, or a single mom that she can only come to the food bank three times per year, doesn’t take into account their individual needs. Nor does it level the playing field so everyone in our society has the opportunity to succeed.

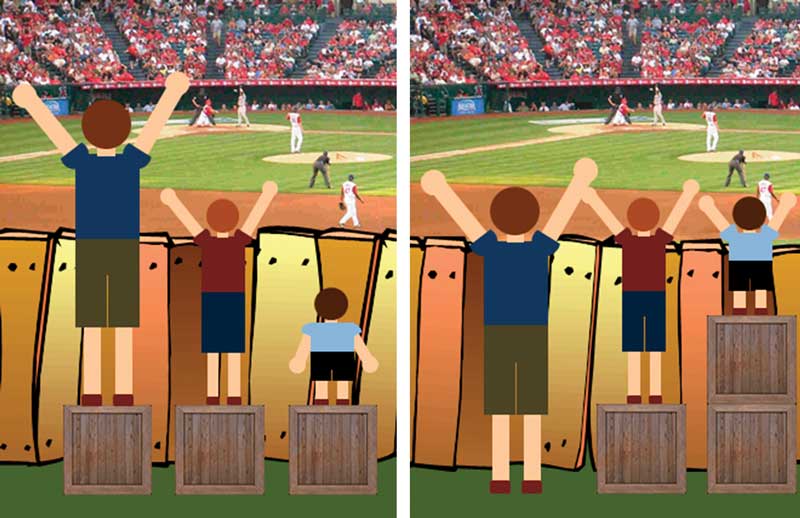

Procedures that treat everyone the same are usually implemented to make our operations efficient and fair. But equality is not equity. If we believe that God has a plan and purpose for each person, we must also believe that his plans have been frustrated in the lives of those who come to us for help by circumstances sometimes beyond their control.

Isn’t it our role to balance the scales so that God’s purposes might be accomplished?

Questions for Reflection:

Major Juan Burry is the executive director of South Vancouver/Richmond Health Services in the British Columbia Division.

Illustration: Courtesy of Craig Froehle

At the beginning and end of the 12-week program, the men were given a poster-sized sheet of paper and asked to answer, “Who am I?” At our first graduation ceremony, they read both aloud. The “before” posters usually had a few short statements, such as “I’m an addict” or “I am unemployed,” written so small it was hard for the audience to see. The “after” posters, on the other hand, were filled with expressive and optimistic sentences, such as “I am a child of God,” “I am fearless” and “I am patient with my shortcomings,” written in large letters.

Each man’s testimony shared similar themes. Each one had encountered abuse or trauma, often in early childhood. To provide relief or escape, they turned to alcohol or drugs. Following this were many years of battling addiction. The testimonies concluded with hope that this time around things would be better.

Many of the graduates went on to successfully reintegrate into society. In seeing themselves differently, they approached the world differently. That was an important lesson for me.

Another lesson was more personal. I had to admit to myself—and asked the audience members at the graduation to admit as well—that perhaps the only reason we weren’t in the same situation as these men was because we had a larger degree of social advantage. I wasn’t physically or sexually abused; I didn’t grow up in abject poverty and shame; I didn’t suffer emotional and psychological torment from the people who were supposed to love me. Where would I be if I had? I can only imagine.

Christian social justice means ensuring that every person is given the opportunity to realize their God-given potential. But we must first acknowledge that not everyone coming to us for help began their journey at the same place.

Telling a homeless person that he can stay in our shelter for 20 days like everyone else, or a single mom that she can only come to the food bank three times per year, doesn’t take into account their individual needs. Nor does it level the playing field so everyone in our society has the opportunity to succeed.

Procedures that treat everyone the same are usually implemented to make our operations efficient and fair. But equality is not equity. If we believe that God has a plan and purpose for each person, we must also believe that his plans have been frustrated in the lives of those who come to us for help by circumstances sometimes beyond their control.

Isn’t it our role to balance the scales so that God’s purposes might be accomplished?

Questions for Reflection:

- Social justice is one of our territorial strategic priorities. The first action item is: “Deliver services in ways that respect and value people.” What does that look like? Is it just speaking kindly to people when they come through our doors, or does it require us to provide services tailored to each individual’s needs? How can we make that shift as an organization?

- Another action item states that we will “stand up against situations of injustice that oppress and marginalize people.” When do we do that? In some Canadian cities, the unaffordability of housing is an example of injustice. Are we speaking out against the political and financial systems complicit in this crisis? Building more shelters or affordable housing units doesn’t address the injustice; it just creates ghetto-like neighbourhoods and further marginalizes people.

- Do our theological perspectives regarding the nature of sin negatively impact the way we approach those in need of justice? Do we still view the drug addict in our treatment centre or the violent offender in our halfway house as someone who simply made bad choices and needs to turn to God? How would our service improve if we viewed activities that harm people through a more layered and sophisticated lens?

Major Juan Burry is the executive director of South Vancouver/Richmond Health Services in the British Columbia Division.

Illustration: Courtesy of Craig Froehle

What I liked about the Salvation Army was that they insisted on rehabilitation as the only response to drug addiction. Am I to conclude from this "shift as an organization" that you now support such things as safe supply initiatives? Did you not learn from the 30-year battle inside Portugal and the Netherlands that only rehab truly works? Sad to see the Salvation Army abandon its 156-year history of being effective, only to slide into identity-based Marxism. Shame.