![]()

Key Findings

There exists no stated overarching vision, operating model or principles and values statement for officer human relations, which is a prerequisite for building a strong sustainable human relations system for officers.

Systems Approach to Officer Human Relations

We found that adequate human relations systems for officers are lacking or absent. One of the best ways to mitigating the effects of organizational inequity is to change unhelpful programming. However, equity cannot be written into inadequate or non-existent systems. Without explicit practices, policies and procedures, each interaction and decision is subject to an individual’s personal awareness, competency and bias. Specifically, there appears to be a lack of:

- Best practices, procedure and accountability with respect to the appointment system.

- Consistent guidelines for personal and professional development, performance evaluation and career planning for officers.

- Written position descriptions and expectations for many officers.

- Sufficient time in leaders’ roles to adequately carry out human relations activities.

This lack of best practice and accountability leaves room for gender bias as historical practices are perpetuated as a default. This has a significant equity impact for both men and women but seems to impact female officers more. Research has also demonstrated that women are less likely to be promoted for their potential, or to raise their hand for a “stretch” assignment in professions where they do not see examples of their experience being recognized. Without oversight and accountability to ensure women are engaged, it is likely that women will have fewer opportunities to lead and to learn, thus eliminating them from consideration for higher leadership roles later in their career.

Taken as a whole, their comments reveal an overwhelming feeling that if we do not fix the system, women will leave the organization, or worse, be alienated to such an extent that they will not value the organization.

—Susan Waterfield, National Advisory Board Member

Without systems in place to provide every officer with equal opportunities for professional development and consultation in career planning, women are often left out of opportunities for leadership development and career progression as they push against long-established cultural norms. The task force want to recognize the work that has taken place in attempting to fix pieces of the human relations system, but this work is unsustainable if not developed in a holistic way with a focus on equity.

Effect of Inequality on Female Officers

The interviews conducted for this study uncovered the upset, anger and frustration that women feel about how they are treated in appointments, development opportunities, vocational and career planning, and compensation. One woman shared, “My position changed …. and no one told me. When I asked why my position changed and I wasn’t told. They said they ‘forgot about me.’ Another said, “During a move cycle, our divisional commander told us that the next move there was an option for my husband but that they ‘would find something for me.’” Taken as a whole, their comments reveal an overwhelming feeling that if we do not fix the system, women will leave the organization, or worse, be alienated to such an extent that they will not value the organization. The persistent inequality was further emphasized by multiple comments to this effect: “In our organization women have to be above average to be noticed while men need to be average.”

Well-Defined Human Relations Functions are Essential to Combatting Inequality

Position Descriptions

Position descriptions are foundational for recruitment, training and development, performance assessment, career planning, etc. Many officers do not have access to up-to-date positions descriptions. This problem is exacerbated when position descriptions are shared between spouses (such as with corps officers). Equitable division of duties should be determined, either by the couple or in consultation with them, and signed off by a direct supervisor. This is currently not a regular occurrence. In the absence of clear expectations, it becomes much easier for bias and perceived value to be applied by those who are not close to the day-to-day work. Clarity of scope, expectations of role and specific responsibilities are the basis of task execution and role planning. While many roles have additional duties as required, a foundational understanding of expectations allows for both women and men to effectively articulate when they are experiencing an inappropriate change in scope and clarify how they can make a difference in their work.

Performance Evaluations

The “Hard-to-Stay” survey, conducted by the Pastoral Services department, indicates that 74% of officers are either dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the current performance assessment and feedback system of PEAC (Performance Excellence and Coaching). Some officers shared, “It is often another ‘check the box’ with very little follow-up and very little accountability;” “A waste of time—no accountability or follow up;” and “It has no connection to how I’m appointed—why should I bother?”

We can confirm that up-to-date PEAC assessments are not available for approximately half of the officer force, and that even when they have been completed, they often do not factor into the appointment process.

Performance evaluations provide an important opportunity for officers to learn about how they can grow and provide more objective evidence of potential for leadership and future role assignment. A robust system provides actionable feedback and informs both appointments and development planning for the future. It also eliminates recency bias when leaders are deciding on participation in learning programs or considering individuals for leadership.

Officer Appointments, Including Default Appointments

When we were at THQ and I was my husband's assistant, I found it hard to find my place. How can we cultivate and see women if they are in a marriage and their husband is more high profile? The wife is likely to get lost.

A fair, transparent and equitable process of applying for all positions does not currently exist, nor is the selection process for appointments clearly outlined in a policy. Officers also do not have access or opportunity to review the position descriptions to determine whether they are qualified to fill a mandated appointment. This problem is exacerbated when the male is appointed to a position and the appointment considerations for the female officer are not handled in an equal manner. If these processes existed, it would build a sense of autonomy that is lacking among officers.

We have received significant feedback from officers which clearly demonstrates that default (secondary) appointments are deeply problematic to the individuals who receive them as well as to other officers who see this lived out. While this occasionally happens to male officers, it is much more likely to happen to female officers. Although many in default positions make every effort to contribute well in their position, their opportunity to do so is detrimentally limited by the practice.

Statistics and anecdotes reveal that default roles for women officers are not limited to Women’s Ministries. There have been instances when a man is given the role of executive director, for example; and his wife is appointed as a chaplain, regardless of whether they are trained or passionate about this type of work. Similarly, there appears to be no consultation or consideration given to which spouse will be given the added designation of community ministries officer if both spouses are appointed as corps officers. While the Gender Equity Task Force recognizes that this particular added designation is often tied to funding and not necessarily to position descriptions and responsibilities, this is not always communicated to the officers given the appointment. As with many other default appointments, this also disproportionately affects women. Of great concern, also, is that a recent audit of staff officer appointments to CFOT (a training ground for future officers) revealed a practice of intentionally appointing the married male officer to the primary role with the married female having a default/unintentional appointment.

Better planning, with embedded equity principles, is required in appointment planning.

While we applaud the efforts to create a talent pool for Area Commanders and acknowledge the expressed desire to expand this for other positions, we believe that officers should have an opportunity to express interest in any available position on the Officer Annual Change Information form (proposed Appointment Planning Summary form). The Officer Annual Change Information (ACI) form is extremely limiting in the types of information officers can give. For example, there is no place to express interest in a Women’s Ministries role, emphasizing the understanding that this has been a default appointment rather than sending a message that anyone with a passion in this area could be considered. It is also strongly recommended that women and men be considered for distinct roles should there be no opportunity suited to one party or the other in a single appointment. This can include fully leveraging the now-evidenced powers of remote work to allow one partner to support a headquarters role even while the other may be working in a different ministry.1

________

[1] The role of Director of Spiritual Formation traditionally goes to the female spouse of the Training Principal. In auditing appointments over the 17 years that CFOT has been in Winnipeg, men are typically given the role of “authoritative” head of CFOT and the woman given the emotional spiritual role. Recent history reveals that the only women who have ever filled non-traditional appointments were single.

Officer Development

It is recognized that officers have training and development opportunities. It appears, however, that the way these are managed lacks clarity, consistency and comprehensive planning. Officers interested in education beyond the bachelor’s level are currently being told that this is by invitation only, and yet some education at the higher level seems to be approved upon request. The lack of clarity and transparent communication on this matter has led to a sense (whether real or perceived) that opportunities are offered inequitably.

My capacity and growth as a leader has been self-guided, I have had to learn on my own what it looks like to lead.

Is it up to the officer to seek out training and development opportunities, or is it the responsibility of the organization? We believe it should go both ways. Officers should be encouraged to initiate development opportunities. When this happens, they should have someone they can talk to about their development goals and how they fit with The Salvation Army’s long-term plans for them. The organization needs a plan that supports the needs of the individuals as well as the organization’s needs.

Furthermore, a temporary positive bias towards officer development should be given to female officers, as they will need greater immediate supports if they are to succeed. A recent open call for Area Commander candidates garnered only 4 women of the 20 applicants. This reveals a barrier of hesitancy for women to step forward for leadership, which can be rectified with greater confidence that results from individual development. It may also suggest that there is insufficient mentorship for women that would encourage them to step forward. This practice has been demonstrated in other environments to be particularly effective.

Vocational Planning

The number of officers is shrinking through retirements, resignations and reduction in new recruits. A formal vocational planning system will help the organization plan for future needs to ensure that sufficient candidates with the right skills and experiences are available. General Peddle has stated, “Every territory and command is being asked to partner with IHQ in succession planning, developing a pipeline of leaders who, over time, can equally be considered for leadership positions at every level of the movement. This requires local leadership to initiate appropriate personnel strategies with the goal of developing all leaders under their care.”2

Currently, the opportunity to express interest in a specific position or vocational stream within The Salvation Army is extremely limited for officers. The current ACI form minimizes the types of positions officers can express interest in. Most importantly, there needs to be a place where women, and all officers, can safely discuss their vocation, concerns and issues.

All officers should have the opportunity to openly discuss their interests, gifts and willingness to lead. When clarity is disallowed, both the decision-maker and the individual are at a disadvantage. Although not all desires can be matched with required roles, communicating the demand provides a starting point for discussion and enables leaders to have meaningful dialogue on the intersection of individual gifts and organizational need.

________

[2] Peddle, General Brian. “Lots of Talk, Not Enough Action? Making Gender Equity a Reality.” The Officer, April-June 2021.

Leaves

The steps already taken towards reviewing and modifying the Parental Leave policy have been celebrated across the territory and are already making a marked difference in the lives of new parents, particularly new mothers. We applaud those who received this recommendation favourably and the steps taken to put this policy into practice so quickly. Thank you

A review of policies concerning other leaves revealed that current policies around medical and parental leave for single officers result in single officers being disadvantaged. Because the overwhelming majority of single officers are female (58 women to 9 men at the time of research), this became an area of attention for this task force. There are issues that on the surface may appear to be “gender-neutral,” e.g., policies and benefits that refer to, and apply to, “all officers.” But when these policies are operationalized, female officers are placed at a distinct disadvantage, particularly single female officers. For example, in the instance of married officers, if one spouse goes onto Short-Term Disability/Long-Term Disability, it has little impact if the provision of a vehicle and quarters are withdrawn. A married officer on LTD won't lose any resources, since the car and quarters will still be provided to their active-officer spouse. However, for a single officer, when these provisions are withdrawn, the single officer is left without transportation or home.

Comprehensive Compensation

While officers are equally compensated when it comes to a financial living allowance, there are marked inconsistencies with respect to non-monetary compensation such as housing and other benefits.

Many of these non-monetary compensations fall under the responsibility of the ministry unit and there is marked inequity with respect to accessing these benefits. For example, the quality of housing is often tied to the financial health of a ministry unit; ministry units that are financially affluent tend to have better housing for officers than ministry units who are struggling financially. This provides a framework of “have” and “have-not” appointments that disproportionately affects women, in particular when single officers (majority of whom are women) tend to be appointed more often to financially struggling ministry units.

As in the case with leaves, the current compensation model for single officers creates an inequitable situation where women will struggle significantly more than married couples to adequately provide for their own needs during active officership and into retirement. For example, whether a vacation is at a campsite or at a hotel, the cost for one person is the same as the cost for two persons. However, a single officer receives half the vacation allowance of a married couple. Salvation Army pension for a single officer is about half that of a married couple, but the cost of an apartment is the same for both married and single. There are real challenges for single officers when it comes to day-to-day living expenses and preparing for retirement.

Uniform Wearing and Dress Code

The critical theological underpinnings of the uniform reveal the wearer as a “servant,” embodying “a loving greeting” from God and reflecting a “testimony about the grace of God in Christ.” (O&R for Soldiers). Dress code/uniform policy, up until recently, reflected culturally and socially gendered expectations for dress rather than the organization’s original theological and missional purposes.3 Secular ideology4 around gender and dress has no theological bearing and, therefore, does not have a place in informing dress for Salvation Army officers and soldiers. Women in uniform experience scrutiny around dress with implications for stereotyping and body shaming.5 Recent policy changes have sought to address the inequitable restrictions of previous dress code/uniform policy. However, more is required to recover the theological and missional purpose of the uniform.

While this policy update was important and necessary, it has failed to address the deep-rooted cultural foundation of uniform-wearing in certain contexts, where uniform-wearing and uniformity to specific cultural ideals are interconnected through shame-based comments, practices and more.

Even with this new policy in place, body-centric comments to female officers continue to take place. A recent post on the Salvationist Facebook page includes this comment, “So good to see women officers and soldiers in skirts. I’m so sick of pants in the pulpit I could scream;” “What is up with women officers, cadets and soldiers wearing dress pants as their uniform? Is this something new? I think it looks very unattractive.” While these may seem like isolated comments, discussions with corps officers highlight that these comments are similar to comments made to them from congregants. As such, female officers and soldiers experience the uniform and consequently their bodies as a site of gender politics.

Lastly, the uniform has been utilized in colonial ways6 and this limits cultural considerations that may accommodate those with different cultural backgrounds.

________

[3] The original purpose of a uniform that represents the religious convictions of faith and service, while also rejecting worldly vanity and emphasizing practical applications, needs to be rediscovered. The practicality of the uniform in the early days of The Salvation Army included the carrying of an umbrella (useful for leading singing and processions in the street) and the wearing of a wide-brimmed bonnet (the Hallelujah bonnet) to protect its wearer from projectiles when riots would break out during open air meetings. Source: Dedicated Followers: Uniforms and The Salvation Army’s Attitudes to Fashion | The Salvation Army

[4] Jansens, Freya. (2019). Suit of power: fashion, politics, and hegemonic masculinity in Australia, Australian Journal of Political Science, 54:2, 202-218, DOI: 10.1080/10361146.2019.1567677, p.210.

[5] Interview data: “In my last meeting with my staff advisor prior to leaving CFOT, I was asked what I would wear to a pool party—would it be a bikini and short shorts? I thought to myself, this is all you have to say to me before I leave?” “There was a warmer sweater that I wanted to wear because it is cold in Winnipeg. It is sold at trade but I was told I couldn’t wear it because it was not feminine enough.” “Heels—telling women that they have to wear these—it is insane.”

[6] Much research has been done on the importance of dress in colonization. In many situations, the colonizing Western culture mandated the colonized people adopt Western ideals of dress as one aspect of cultural assimilation and, in some cases, spiritualization and/or religious conversion. For example, a desire to cover the people’s “nakedness” and assume a more “modest” dress was seen as an important aspect of converting many African nations to Christianity.

Closer to home, “In the Indian Residential Schools, dress was aggressively changed to fit with Western ideals of civilization. Indeed, it was a crucial component in attempting to fulfil the Indian Residential Schools’ purpose. As dress is an embodied object, it reflects identity. The Indigenous epistemology embedded in how dress was created, worn, and cared for was often violently removed and replaced with European-styled school uniforms in an attempted reorientation to European standards. These attempts were ultimately failures as how the dress was implemented, the condition and care of the clothes, and the punishment enacted were all contrary to achieving assimilation. Rather, students were taught body shame and were reminded of their position at the bottom of Canadian society’s hierarchy. While other elements contributed to trauma and the cultural genocide perpetuated in residential schools, dress is an important factor because clothing is the first object a body interacts with.” To read more, see https://www.fashionstudies.ca/indigenous-dress-theory, We believe parallels can be drawn between uniforms in residential schools and the enforced wearing of The Salvation Army uniform.

What’s more, uniform wearing can create a power imbalance. “The cultural distance and power imbalance between “center” and “periphery” were visibly enacted in styles of dress. Clothing styles were employed in Europe—and in Africa—as measures of cultural advancement in an evolutionary progression from ‘primitive’ to ‘civilized’ status.” Source: Colonialism's Clothing: Africa, France, and the Deployment of Fashion. Academic Journal. by Rovine, Victoria L. Design Issues. Summer 2009, Vol. 25 Issue 3, p. 44-61. 18 p. 3 Black and White Photographs. DOI: 10.1162/desi.2009.25.3.44., Database: Academic Search Premier. If we truly want to “decolonize,” further conversations regarding uniform-wearing are necessary.

Recommendations and Rationale

A Human Relations System for Officers

B1. We recommend that The Salvation Army adopt a systemic approach to human relations for officers as needed. It should start with a shared vision, clearly stated objectives, inclusive equity principles and clear outcome measures.

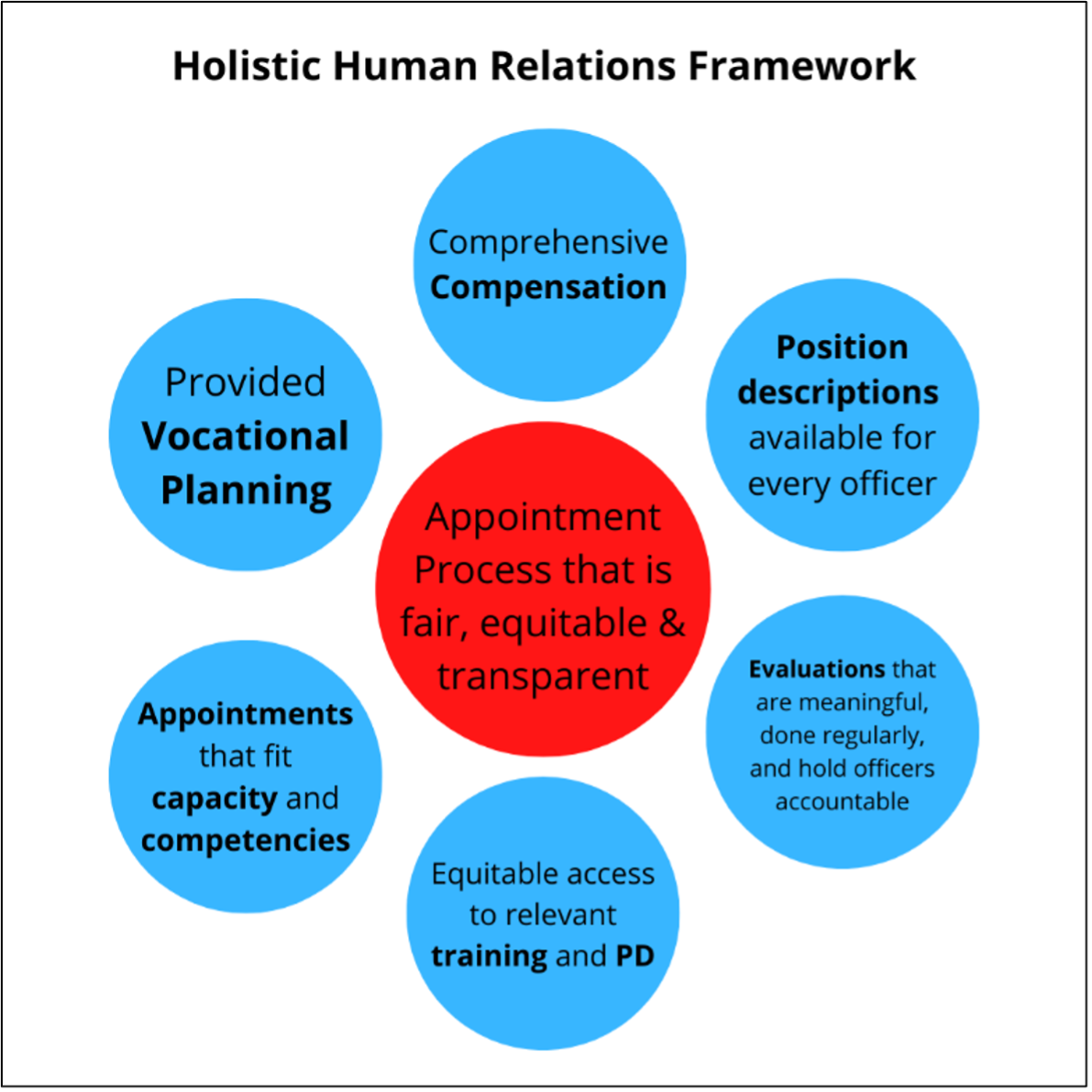

The illustration above illustrates one view of a holistic approach to a human relation system for officers. With the appointment system as a focal point, all other human relations entities will support the task of putting the right people in the right positions to further the mission. We need a standardized appointment system with equitable training and development opportunities regular and effective performance evaluations, career paths and vocational planning and well defined position descriptions that transparently communicate the needs of the organization.

“Gender-neutral” language must not artificially mask inequitable impacts of policy and process. While inclusive language reduces bias, by itself it does not change the impact of programming. Defaulting to language such as “all officers” does not inherently change the program to ensure an equitable result. Any policy change should be undertaken with support of the Gender Equity Advocate and the lens of root cause and impact.

Position Descriptions

B2. We recommend that every officer has an objective position description and all position descriptions be reviewed by supervisors regularly to ensure organizational and individual needs are being met.

It takes many types of positions to make organizations work well. The right balance of generalist, specialist and leadership positions are the basis for system that can deliver on the mission of an organization. Defining position types and/or position descriptions can be used as a building block to ensure equity between position types, and that officers have equal opportunity to be involved in positions best suited to their vocational path and competencies.

Performance Evaluation

B3. We recommend Performance Excellence and Coaching (PEAC) be revised or replaced with an evaluation and coaching model that is effective, supports gender equity, is integrated with the appointments process and holds all officers accountable.

Performance evaluations are required to ensure the right people with the right skills and abilities are placed in the right positions, and to support vocational paths. They are also used to improve performance and help individuals build the skills needed for their positions. Performance evaluations should work in tandem with training and professional development. Often equity principles are built into both the performance evaluation process and training.

Whether it is PEAC or another form of performance evaluation, these tools must be meaningful, held regularly and hold officers accountable. They should also be used for each officer throughout the appointment process as a helpful tool in matching the officer’s passions and competencies with the appropriate appointment.

Supervisors should also be held accountable for the completion of performance evaluations. Currently, Area Commanders perform the majority of PEAC reviews for officers. Based on the current scope of responsibilities of the AC role, the success of PEAC is not possible. For any performance evaluation to succeed, the role of the AC needs to be reviewed to allow for consistent, thoughtful, thorough performance reviews. In addition, the new AC Brief of Appointment is more supervisory in nature and ought to be revisited to ensure space for the pastoral elements of being known and valued by the organization, of which the AC is the first point of contact.

B4. We recommend that the role of the Area Commander be re-evaluated, and their scope and oversight be reduced or provided with additional administrative support, so as to spend adequate time on the development and other human resource needs of the officers within their scope.

Training and Personal Development

B5. We recommend that clear, transparent and fair criteria are utilized for the selection of leaders for training and appointments—and that a review process be made available for anyone who feels they have not been adequately considered.

Without thoughtfully developed and widely communicated criteria and processes, qualified women (and men) may be missed. It also risks wasting or inefficiently assigning resources to those most likely to benefit from and share their experiences.

B6. We recommend a temporary positive bias towards the development of female leaders. This should include a regular stewardship review to ensure continued improvement in representation.

To address inequities of the past, realities of the present and opportunities in the future, a more intentional investment in women is a wise allocation of resources. The goal is to provide significantly more opportunities for women to address the lack of opportunities they have had in the past. This bias should remain in place until female representation outcomes are seen in leadership. This may be established as a minimum expectation or in a specific designated resource pool that allows for more women to participate in learning opportunities in the near term.

B7. We recommend that, as well as ongoing formal leadership development, just-in-time learning opportunities be designed and delivered for women moving into new leadership roles, and that these take into consideration the different leadership realities women may face. This should include mentoring, sponsorships, coaching, peer mentoring and/or book and conference budgets as well as live and virtual training. This program should be documented and reviewed regularly.

Women leaders often experience additional pressures including family responsibilities, push back from traditionalists, difficulties being heard, a sense of isolation, closer scrutiny and higher expectations with more limited resources.

B8. We recommend mandatory leadership training for all leaders that includes quality, facilitated time spent discussing the theology, ideology and practice of creating environments in which both men and women can thrive and work well together. This should be included in CFOT curriculum. We may need external voices to assist us with seeing our own blind spots.

As our goal is full engagement, not compliance or resistance, we must provide opportunities for all to see the importance of this topic, develop skills in working across gender, and understand how they are contributing to or working against our preferred future of men and women partnering together in God-honouring and Kingdom serving ways.

Officer Appointments That Fit Capacity and Competencies

B9. We recommend that the Officer Appointment Process be redesigned to effectively match capacity and competencies to the requirements outlined in position statements. This process must be captured in an official policy/procedure that is accessible by all officers.

B9a. We recommend the Officer Annual Change Information form be expanded to support vocational planning and matching capacity and competency requirements.

B9b. We recommend more equitable access to positions and relevant training and professional development be built into policies and processes, including posting more positions and training opportunities to ensure fair and transparent access, i.e., the AC talent pool model should be expanded to support other positions.

B9c. We recommend the rationale for an appointment change be communicated with each officer move and that the timeframe for communicating annual changes be increased to accommodate these conversations. This requirement should be captured within the policy for Officer Appointment Process.

The organization would benefit from building an appointment and development process that better matches officers’ capacities, skills, and passions, through effective and equitable evaluations, training and professional development and vocational planning. This may require more flexibility in offering split appointments for spouses but will ultimately benefit the mission of the Army by fitting capacities and passions with the work requirements of the organization.

A fair, transparent, and equitable process of applying for all positions and development opportunities will build a sense of autonomy that is lacking among officers. The appointments and development process should clearly be outlined in a written policy.

Also, posting as many positions as possible leads to equitable access. Posting of positions allows for a breadth of both female and males candidates to apply and be interviewed. Every effort should be made to include both male and female candidates. This approach can begin to reduce any gender conscious or unconscious bias that may exist.

Processes such as these, if applied universally to each officer, could be one solution to the default appointments issue. The system cannot continue its their current form. Consideration must be given how joint appointments are made so that both appointments are given equal consideration.

Provide Vocational Planning

B10. We recommend a vocational/career planning system be put in place, starting at CFOT level and provided to all officers as it becomes available. This includes long-term development, early identification of senior leadership potential and succession planning.

A sound vocational (career) planning system that coordinates the efforts of Pastoral Care, Officer Personnel and Career Planning teams, as well as supervisory mentoring, supports the organization and equity goals by giving officers, cadets and potential candidates a better idea of what a vocation in The Salvation Army looks like.

Decisions will need to be made regarding who at THQ and DHQ will be involved in the various aspects of career planning. The persons leading this system should be well respected male and female officers (vs employees) in order to ensure both career and covenant remain centred in the conversation. A consistent, accessible approach across the territory is crucial.

To support integrated vocational planning, there needs to be stronger linkages to the appointment process and training and development.7

Comprehensive Compensation

B11. We recommend a full investigation and regional assessment of housing costs, with the goal of ultimately including all officer benefits (including housing costs) in the Officer Benefit Levy.

B11a. We also recommend the policies listed below, impacting single officers, be reviewed for the purposes of bringing equity in terms of benefits, allowance and retirements.

Housing is not equitable across ministry units, something that affects women significantly more than it does men. Financially strapped ministry units that can only financially support a single officer often also cannot support adequate housing upkeep. Because there are more single women officers than men, more women find themselves in single officer appointments such as this. That said, there are also dual-officer appointments that also struggle to financially upkeep a quarters.

The interviews conducted by the Gender Equity Committee found many examples of ministry units where an office space was not provided for the female officer in the corps or CFS building and women were thus expected to work from a home office. In this way, insufficient accommodation also disproportionately affects married women.

In addition, compensation systems for single officers require more equitable measures. While gender equity is about male to female issues, there are additional inter-gender equity issues in terms of how single officers (mostly female) are treated compared to married officers. The inequity of our current policies and procedures in terms of allowances, leaves and benefits impacting single officers ought to be reviewed and revised to bring equity. In addition to retirement and RRSP contributions/allowances, the following policies require revision to this end:

HR 09.001 Absence for Medical Reasons

HR 09.003 Allowances—Officers

HR 09.022 Parental Leave

Dress Code

B12. We recommend that recent dress code policy (HR 09.035) changes be re-socialized, aligning mission and calling as formative and foundational to the change of policy and uniform wear.

There seems to be some misunderstanding regarding the recent changes to the dress code (as seen by the continued public confusion regarding women wearing pants, the lack of tunic in the winter, etc.) The way this policy was communicated across the territory seems to not have cascaded down through the ranks. As such, we recommend that this policy be reiterated with a plan for communication to all levels of leadership and membership.

B13. We recommend that a policy be introduced that outlines a process for addressing dress-code violations by designated personnel only. Sensitivity training should be mandated for those given this responsibility. Further, we recommend guidance and sensitivity training for supervisor/department/DHQ/CFOT staff responsible for addressing dress-code violations.

This is not an attempt to formalize the policing of uniform. Rather, it is meant to reduce the high level of organic, negative commentary on the wearing or mis-wearing of uniform.

B14. We recommend that no DHQ, CFOT, local music group leader, etc., be permitted to increase or change the uniform policy standards.

While we recognize that there may be extenuating circumstances, such as the need for cultural sensitivities in one-off situations, we are concerned that, for example, certain music groups may still mandate the wearing of the skirt for women. Processes should be in place which prevent this.

B15. We recommend that an external and internal study be conducted to provide a culturally informed discussion concerning the uniform and dress code policy and that training be provided on the effect of uniform-wearing on specific populations.

Section Summary

As a Christian organization, we should exceed societal and professional norms when it comes to caring for our people. We are called to love our neighbours and to care for all who are made in the image of God. We should, therefore, aspire to set an example in how we treat both officers and employees. While officers are not considered employees, and as such are not captured in equitable policies that hold the organization and employees accountable to each other, our biblical and theological foundations call us to a redemptive, ethical treatment of officers that surpasses secular standards. This becomes even more essential in an appointment-based system where officers are asked to surrender so much of their personal autonomy in order to fulfil God’s calling upon their lives.8

Why be an officer? In our territory you can do the same job as an employee, get higher pay, better benefits, and more control over your life.

We fully believe that the impact of a holistic and equitable human relations system for officers will result in:

- Increased attraction of new officers

- Better retention of current officers

- Increased missional productivity and performance of officers

________

[7] Anecdotal evidence suggests that the current policy may not be being applied equitably, and there appears to be a lack of transparency or consistent messaging regarding continuing education and high-level development opportunities.

[8] The “Hard to Stay” study, conducted by Pastoral Services, found that only 12% of officers would recommend officership without reservation. One officer said, “I would not recommend officership to one other soul. I can’t do it in good conscience—I feel it is an unhealthy system, unhealthy work environment, with unhealthy expectations.” Another said, “Why be an officer? In our territory you can do the same job as an employee, get higher pay, better benefits, and more control over your life.”