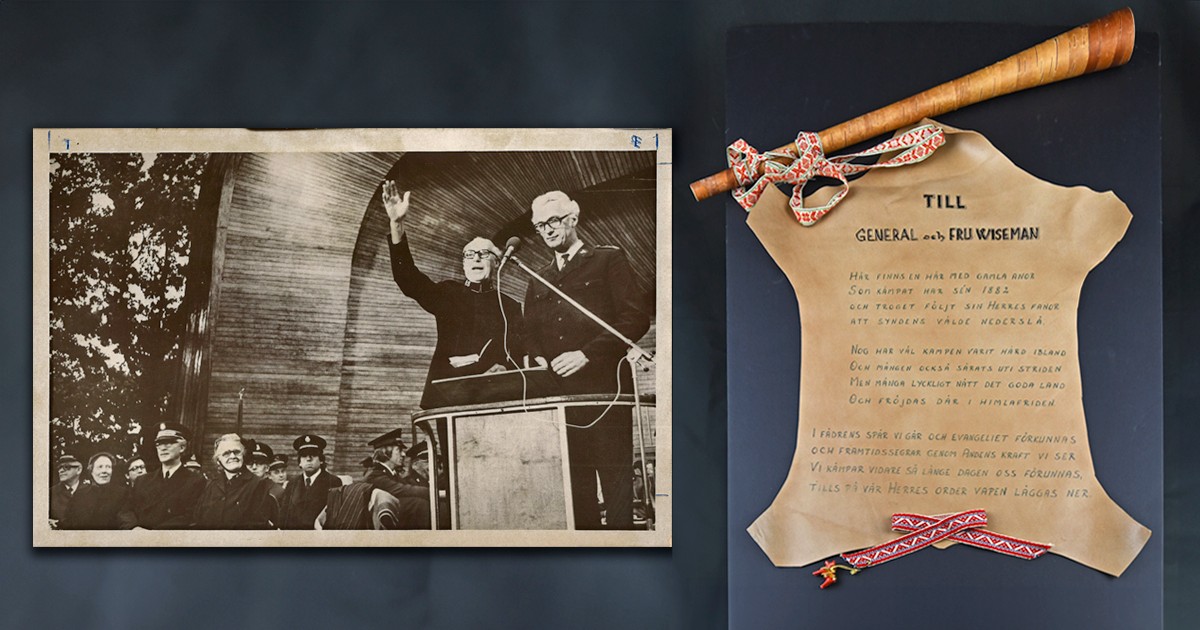

Walking Gently Together

Tracy Desjarlais, Indigenous liaison, shares the importance of building bridges between the Army and First Nations.

Features“A handshake goes a long way,” says Tracy Desjarlais (Piapot First Nation of Saskatchewan), Indigenous liaison for public affairs and emergency disaster services (EDS) for the Canada and Bermuda Territory. “And to build trust within the nations, it’s important for us to be present.” As part of The Salvation Army’s commitment to establishing this

Read More