“Hello,” calls out John Phipps, a volunteer with The Salvation Army in Niagara Falls, Ont.

The man doesn't move.

John steps into the motel room, one hand holding a tote filled with brown paper bags. Inside are sandwiches and juice boxes.

The air is foul inside the room. A mix of ripened body odour and the stale, musty stench of a rented space steeped for decades with the sour smells of desperate people.

John calls out again. The man still does not move; likely sleeping off a booze-induced haze.

For now, that's about all John can do.

“Have You Got a Sandwich?”

The man is one of the regulars. And on this Wednesday, John and Karen Johnson, a mobile outreach worker for The Salvation Army, have other motels to visit. Their van is loaded up with egg-salad and tuna sandwiches, made by volunteers earlier in the day at The Salvation Army's Niagara Orchard Community Church.

Every week, they visit a circuit of motels, knocking on doors and handing out sandwiches to people who call a motel room home. They are people on unemployment or disability. Rent is cheaper than an apartment since utilities, phone and cable are usually included. They don't need first and last month's rent, or references. There's usually no kitchen, so they cook with an electric frying pan, slow cooker or microwave.

Sometimes the need seems overwhelming. “You do what you can,” says Karen.

When the program started three years ago, she delivered eight sandwiches. On this night, they will give away 74.

Once last year, they had just handed out their last sandwich when a woman came running across the parking lot yelling, “Have you got a sandwich for me?”

“It broke my heart,” says John.

They went back to the church kitchen and quickly assembled some sandwiches, then returned.

“Some of them, it's all they have to eat all day,” says John. “When they rely on you….”

“Knowing Someone Cares”

Fact is, it's about more than a sandwich.

It's about reaching out and connecting. Building a rapport with people who can't or won't reach out to regular daytime programs. Connecting people to services that could help improve their lives.

The Wednesday sandwich delivery is part of The Salvation Army's Niagara Mobile Outreach program. Six nights a week, a truck travels across the region, stopping in parking lots, apartment complexes and other public spots, offering food—everything from sandwiches to hot meals—and an onboard counsellor to anyone who needs help.

Many families rely on the meals.

When the program started three years ago, she delivered eight sandwiches. On this night, they will give away 74.

“People have a hard time reaching out for help,” says Carrie McComb, a community outreach supervisor in St. Catharines, Ont.

Pride and the stigma of living in poverty are barriers, she continues. Program success is measured in lives helped. Maybe a man living under a bridge is put into a shelter. Or someone in a shelter finds affordable accommodation.

“It's not just about a sandwich,” says Karen. “It's about their knowing someone cares.”

“Heartbreaking and Heartwarming”

The pair pull in behind a hotel and Karen knocks on a couple of doors, ones they've delivered to in the past. “Salvation Army. Would you like a sandwich?” she shouts. No one answers.

And then, a door opens.

“Yes, please, I'd like a sandwich,” says the man.

For most of his life, 57-year-old Bill Morgan worked doing home renovations. But business slowed down and his health took a turn for the worse.

“All of a sudden, I'm in a shelter and I ended up here,” he says.

He gets $626 on Ontario Works and pays $500 for rent and $35 for a cellphone.

“It means by the third week of the month, there's no food left,” he says. “Then you just count on the blessings of strangers.”

Karen and John walk across to the next unit.

A three-year-old girl in a red sweater comes running with outstretched arms toward Karen, then skips over to John and pulls a couple of brown paper bags from the collection inside his tote. She gives one to a woman sitting on the sidewalk; they eat them immediately.

John and Karen pull away in their van as the little girl in the red sweater rides around on a three-wheeler.

“It's heartbreaking and heartwarming at the same time,” says John.

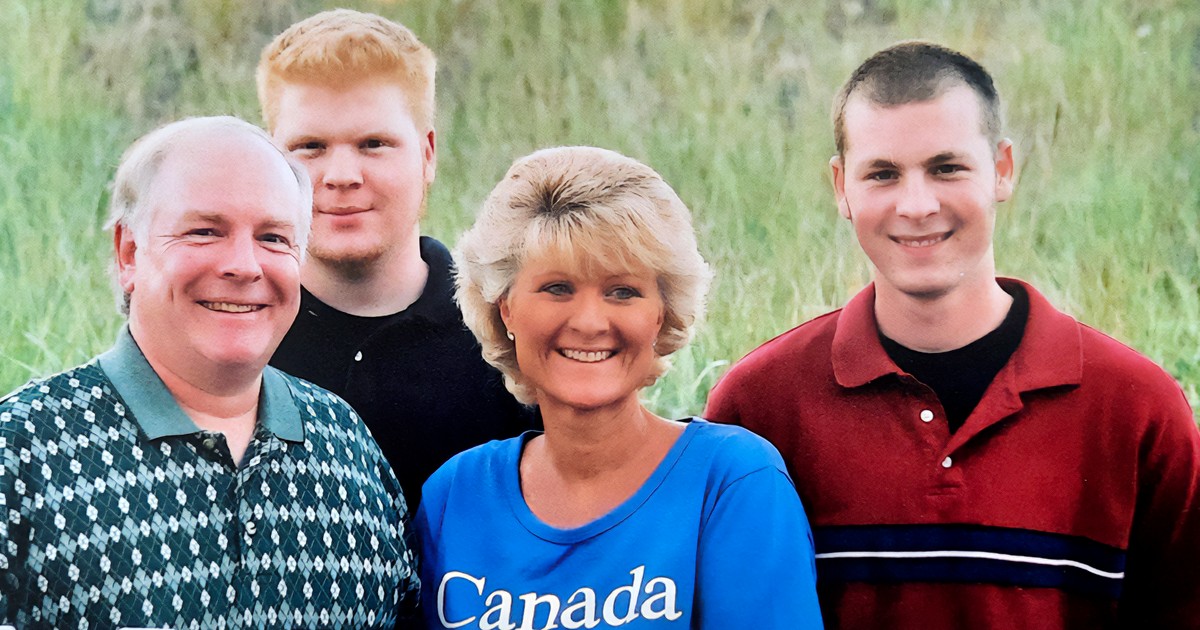

It's in the Bag: Karen Johnson and John Phipps at the start of their self-appointed rounds

It's in the Bag: Karen Johnson and John Phipps at the start of their self-appointed rounds

Seeing Past Closed Doors

Down the road, the pair resume knocking. The first door opens enough to allow a man's arm, up to his elbow, to emerge. Karen hands him a brown bag, and the door closes.

Next stop, Brian Maltby, 58, leans against a white pickup truck parked in the lot, and talks about his pet rat that died. He buried it across the road, in a grassy area next to a strip club's parking lot.

He gets the last two sandwiches of the night.

On the way back to the church, Karen becomes philosophical.

She knows there are many who struggle to feel compassion for the people she sees every week, and she often hears the question: Why should I care?

“We're so ready to judge and not look past that closed door, and into a person's life and not see the pain,” she says. “A motel is quick, easy and simple. It's easy to be judgmental, until you actually see how people live.”

Karen has looked past many closed doors.

“It makes me feel good that I can help them,” she says. “I've listened to a lot of their stories.

“I get to see their hearts.”

(Reprinted from St. Catherines Standard, August 7, 2014)

Leave a Comment