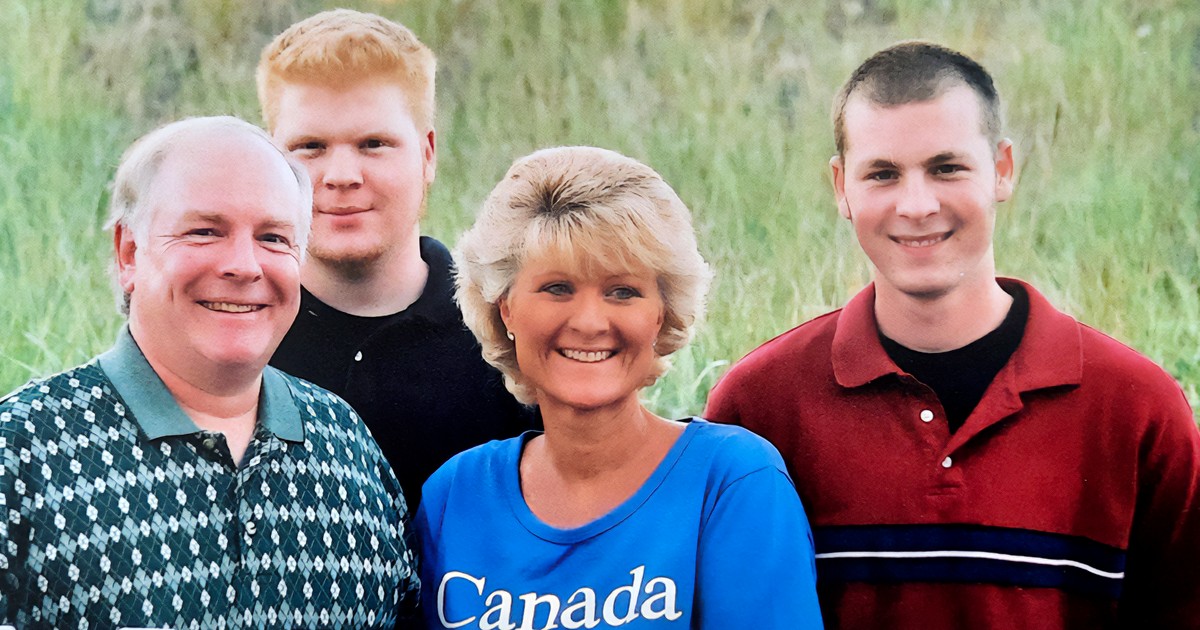

Anne Gregora

Anne Gregora

The aim, says Anne Gregora, who works for The Salvation Army as an adviser on anti-human trafficking and gender-based violence projects around the world, is that at the end of their two-year program they will set up their own business or take orders for items from bigger companies.

On a recent visit to Bangladesh, Anne saw the training centre at work and heard the women's stories of their time in the brothel and what made them leave.

As she explains when we meet in London, England, such stories are providing The Salvation Army with information that helps it tackle trafficking and gender-based violence in the country.

Anne says: “The training centre is a great project for women who are already in the brothels and need a way out. But we want to support many more women and prevent them from experiencing exploitation in the first place.”

Women begin working in a brothel—and sometimes are sold into a brothel—because of what Anne describes as “a way of life” in Bangladesh.

“It's a very patriarchal system. Women are seen as having less value than men or no value. We see it in the way that men pay for their bride—a man buys his wife and has ownership of her. Boys' education is prioritized over girls'. Men are sole income-earners; women don't have the ability to earn. Men are the decision-makers in the family—women don't have a voice.”

Anne says that such a society can lead to women experiencing treatment “that is emotionally, physically, mentally or financially disabling.”

She explains: “If, for instance, a husband has cast his wife out of the house, she is alone, because the structure of society has given her no chance to gain an education, learn skills or earn an income. As a result, she has almost no option other than to rely on the generosity of somebody else or to enter the sex industry. And even when a woman does rely on someone else, she becomes vulnerable because men take advantage of her and sell her to brothels or other exploitative situations.”

Since the women have started to bring in some income, they, too, can make decisions

The Salvation Army wants to address the situations that lead to women being trafficked into a brothel or feeling that they have no choice but to enter one.

“Through our work with women, we're identifying the communities where many of those in the brothels are coming from. So we send people into the communities to build a rapport with the women there and try to stop the flow into brothels.

“By listening to the women in the communities, we have discovered that one of the key issues is that they have no way to generate an income, so they have no control over their lives. In response, we are helping the women to set up self-help groups.”

When she was in Bangladesh, Anne met women benefiting from membership of the groups.

“It is essentially a microfinance scheme. The self-help group will open a bank account with The Salvation Army as a guarantor,” she says. “The women put in whatever money they can and from that pool they can take out loans. With their loan, they start a business or set up a market stall. One of the self-help groups I met wanted to buy a tractor for their farm work.

“The groups also receive education on certain issues, including trafficking. The Salvation Army found that when it initially went into the communities and started talking about trafficking, people didn't know the term—they just knew that people left their village and never came back.”

By giving women financial independence, the self-help groups—which now have more than 100 members—also give women more power to shape not only their future but also the lives of their families and communities.

“When it was only the men earning an income to provide for the family, it meant that they made all the decisions,” says Anne. “But since the women have started to bring in some income, they, too, can make decisions for their family.

“We've also started to see self-help groups go to the authority structures in their community and ask for better sanitation or for a road to be paved. They are making requests that they would never before have been able to make.”

Reprinted from The War Cry, London, England.

Leave a Comment