Imagine a well-liked 22-year-old youth pastor of a small congregation in the United States. One night, after a church event, he offers a 17-year-old girl a ride home. He sees something he wants—something that doesn’t and shouldn’t belong to him. And he uses his power to take it. Driving to a dark and secluded area, he tells her to perform a sexual act. Scared and embarrassed, she acquiesces. Immediately he silences her, ordering her to “take this to the grave.”

It reminds me of another well-liked leader—David, the king of Israel. One night, from the roof of his palace, he surveils a beautiful woman bathing. He sees something he wants—something that doesn’t and shouldn’t belong to him. And he uses his power to take it. When Bathsheba becomes pregnant, David attempts to hide his dark deeds in dark corners, sending her husband to the front line of battle to be killed.

In Sunday school, I was taught the G-rated version of this story. Now, I cannot help but see the connection between power and sexual violence— something we have inherited. Over the past few years, we have been saturated with news of spiritual leaders from every corner of the church using power to abuse and exploit the people they serve. It is exhausting and defeating.

But can we take our cue from the prophet Nathan, who had the courage to confront the king and stand up to injustice? Nathan brought word of God’s prophetic punishment not in dark corners but before all Israel and in broad daylight (see 2 Samuel 12:12). How can we model this leadership?

Cheap Forgiveness

I share the youth pastor story above every year as part of the Ethics Centre’s conversation series on human sexuality and Christian ethics. This case study demonstrates how power and sexual violence intersect, particularly in Christian ministry.

Although the young woman reported the abuse to other church leaders at the time, they did not contact the police, and she was advised to stay silent. Eventually, the youth pastor resigned with little explanation made to the congregation. Gossip turned into victim-blaming. The scapegoated victim left.

Nearly 20 years later, the well-liked youth pastor had become a well-liked teaching pastor at a megachurch. In the midst of #MeToo, the woman contacted him, but he did not respond. Needing to have her voice heard, she shared her story through a blog directed to survivors of sexual assault by church leaders. It made the news, and the megachurch was compelled to respond.

In a livestreamed service, the teaching pastor offered a public apology, claiming he had not realized there was “unfinished business” between them. He asked for forgiveness from the woman—who didn’t attend the church, hadn’t been informed of the service and wasn’t present—and the congregation. Then the head pastor preached a sermon on forgiveness. Then the worship team sang songs about forgiveness. The service ended with a standing ovation.

But viewers expressed outrage. Soon, the teaching pastor was put on paid leave, and the megachurch undertook an independent investigation. The head pastor admitted to knowing about the “incident” prior to hiring his colleague. They both resigned. The church confessed it had been “defensive rather than empathetic” to the situation and committed to engaging programs that prevent abuse.

Today, both pastors lead other churches. As the former teaching pastor opened his new church, he was recorded as saying, “We all have our story. Mine just got national news coverage.”

Systemic Evil

There is no doubt in my mind that God forgives people who commit abuse. We are called to forgive them, too. Forgiveness includes the intentional work of supporting the rehabilitation of guilty parties. However, I hold great doubt that leaders who commit sexual abuse should be reinstated.

Incidents of sexual abuse are morally concerning in many ways. One is immediate and obvious. When a church leader abuses someone in their care, they abuse the power entrusted to them by that person. In exploiting this power, they cause harm that can lead to the kind of trauma that haunts a person for life. This is localized abuse.

Incidents of sexual abuse are morally concerning in many ways. One is immediate and obvious. When a church leader abuses someone in their care, they abuse the power entrusted to them by that person. In exploiting this power, they cause harm that can lead to the kind of trauma that haunts a person for life. This is localized abuse.

With the increasing number of church leaders being accused of sexual abuse, another moral concern is raised: systemic abuse. The sin of one leader is never confined to the local context. Its effects spread. It is possible, said Jesus, for one part of the body to cause the death of the whole body (see Matthew 5:29-30). Localized evil becomes systemic evil, particularly when those responsible to oversee the system don’t hold leaders to account.

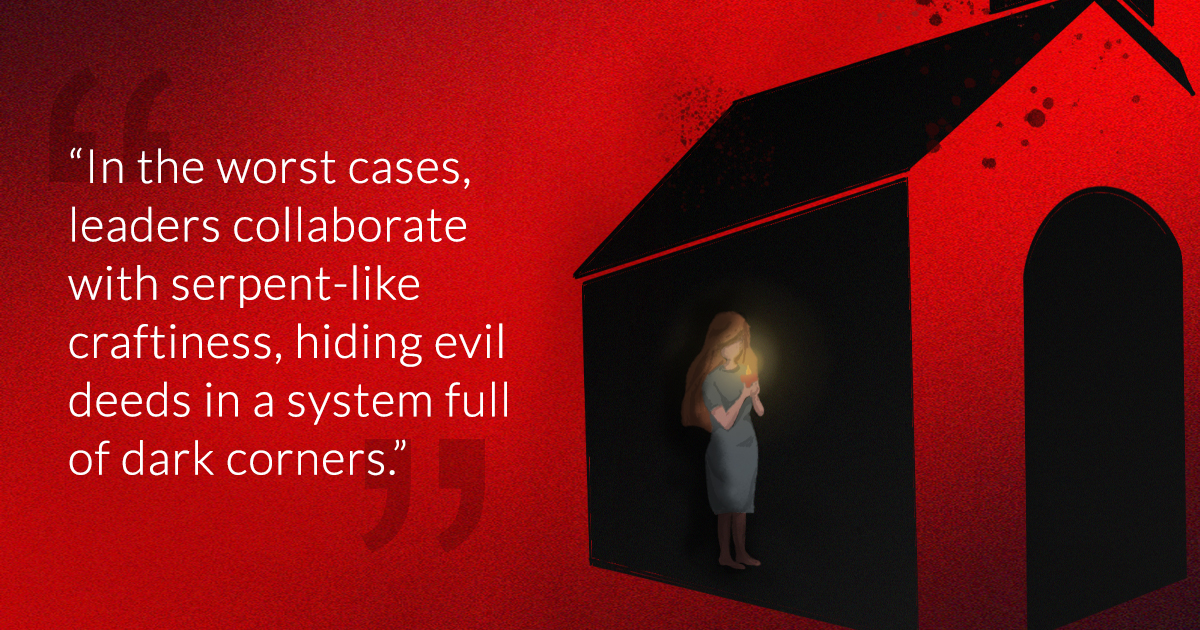

In the worst cases, leaders collaborate with serpent-like craftiness, hiding evil deeds in a system full of dark corners.

This kind of systemic abuse was recently brought to light by an independent review of the Southern Baptist Church (SBC). The SBC is the largest Protestant denomination in the United States. For 21 years, its executive committee covered up more than 700 reports of sexual abuse against women, children and men. One report comes from the story I shared above.

The executive committee saw to it that reports were consistently mismanaged. Its leadership repeatedly claimed that, due to the denominational structures in place, it was impossible to create a central database of cases. What the review found, however, was a highly classified roster of alleged abusers. While holding on to this information, the executive committee continued to allow persons listed on that database to move from one congregation to another. In addition, it refused to hold accountable a former SBC president who was accused of sexually abusing another pastor’s wife. The executive committee encouraged the mistreatment of survivors and their advocates by modelling patterns of intimidation. It recast accusers as “professional victims,” making it more difficult to report abuse.

Sadly, if unsurprisingly, the executive committee resisted sexual abuse reform initiatives. In an internal email, one powerful committee leader argued that demands to bring sexual abuse to light “is a satanic scheme to completely distract us from evangelism.”

Where the SBC goes from here is an open question. Its members now know they have been wronged not only by individual abusers but by a system held together by those with the most power. If the SBC survives this review, it will need to effect deep cultural reform. The review itself recommends many reformative actions, including opening a compensation fund for survivors, creating and maintaining structural resources for prevention and response, and ensuring the hiring process includes background checks and letters of good standing. Most significant, in my view, is that the SBC needs to provide thoughtful, theological reflection on its beliefs pertaining to sexual abuse.

Holding Ourselves Accountable

What about The Salvation Army?

Salvationists value all people as created in God’s image. We are equal in God’s eyes. And because every relationship involves power, we have a shared responsibility to protect one another from abuses of power. But in light of what has happened in the SBC, I felt a need to debrief with our territorial abuse advisor, Nancy Turley. How, I asked, does our territory respond to accusations of abuse? Are we any different from the SBC?

I learned that Turley routinely offers training and education on abuse prevention to officers, cadets and employees. From experience, she knows our territorial operating policy on abuse prevention and response stands out in the Salvation Army world as a robust system of accountability. It delineates a clear and detailed process of response to reports of abuse, indicating that complaints of criminal activity are subject to external investigation. It outlines how care is directed to the physical, sexual, emotional and spiritual harms suffered, whether experienced by the person reporting, the person accused or the larger community. When someone wants to report, they should know, Turley assures, “We will listen, and we will respond!”

However, Turley admits, no system is foolproof. And there are always opportunities for improvement. As we move out of the pandemic, perhaps this is a time to boost awareness about how The Salvation Army has carefully shaped structures of responding to abuse.

All people need to know it is safe to report. How can we ensure that every person in every Salvation Army community knows this? Having the policy visible in all our locations and engaging in more educational workshops would go a long way.

But survivors only trust that their report will be taken seriously and handled justly when they feel safe to report. This is not only a policy matter. It’s a spiritual matter. We need to build communities where everyone feels safe to communicate honestly on a daily basis. This can only happen when we trust one another. So, let’s talk about it. Faith-based facilitation conversations on power and abuse can encourage us to begin exploring this sensitive topic (see salvationist.ca/faith-based-facilitation).

God holds us all responsible to treat others with love and justice. And with great responsibility comes great power. Let’s raise awareness about how The Salvation Army holds leaders to account. Let’s subject ourselves to mutual accountability and compassionate care. Let’s be the kind of people who act in broad daylight and shine light into dark corners.

Contact the Ethics Centre if you are interested in conversations on power and justice through faith-based facilitation. Contact Nancy Turley if you are interested in learning more about territorial responses to abuse.

Dr. Aimee Patterson is a Christian ethics consultant at The Salvation Army Ethics Centre in Winnipeg.

Illustration: Rivonny Luchas

This story is from:

Leave a Comment