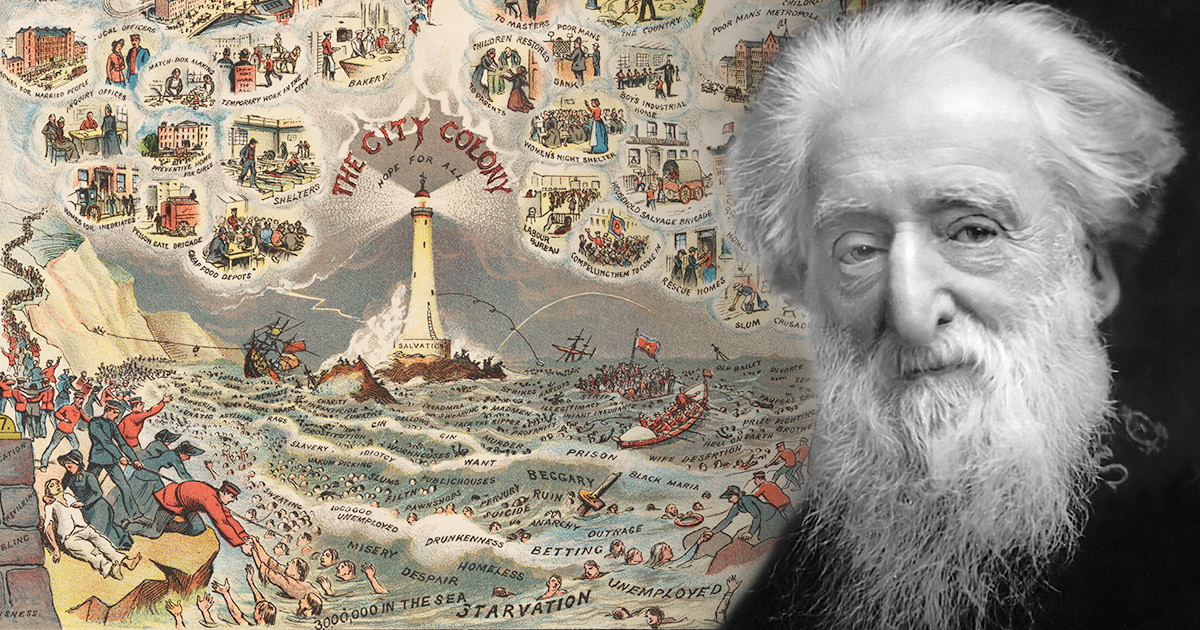

On the 130th anniversary of In Darkest England, and the Way Out, we recall the penetrating words William Booth, the founder and first General of The Salvation Army, penned in 1890 in the preface of his visionary book:

“When but a mere child the degradation and helpless misery of the poor Stockingers of my native town, wandering gaunt and hunger-stricken through the streets droning out their melancholy ditties, crowding the Union or toiling like galley slaves on relief works for a bare subsistence kindled in my heart yearnings to help the poor which have continued to this day and which have had a powerful influence on my whole life.”

In Darkest England, And the Way Out was crafted by Booth as a graphic response to the appalling social conditions in Victorian England and based on the theological foundation that shaped his life. Having trained as a Methodist preacher, Booth’s heart was gripped by the theology of John Wesley who stated, “The gospel of Christ knows no religion but social; no holiness but social holiness.” For Booth, doctrine could never be perceived in isolation from the reality of human life and theology could never be divorced from the human condition. Authentic faith for him meant to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, house the homeless, liberate those enslaved by addiction and prostitution, bring comfort to the lonely, care for the sick, minister to the imprisoned and provide a better life in the here and now, as well as in the hereafter.

By the time the book was published in 1890, The Salvation Army, established in 1865, had expanded its operations to 26 countries on six continents around the globe. This influential book sold 115,000 copies within the first three months, and more than 300,000 copies within its first year of publication.

Booth estimated that 10 percent of the population of Great Britain at that time, about three million people, were living in abject poverty. In the Cab-Horse Charter, he contended that any cab horse in London (the Uber of the day) was blessed with a better life than human beings who fell within this “submerged tenth.” The two points that defined the life of a cab horse was that when he was down, he was helped up and while he lived, he had food, shelter and work. “That, although a humble standard, is at present unattainable by millions—literally millions—of our fellow men and women in this country,” he wrote.

Booth articulated a three-phase scheme to provide “hope for all” suffering from homelessness, poverty and unemployment. First, the “City Colony” phase established “Harbours of Refuge,” which were designed to bring relief to the crippling overcrowding in the urban centers. Second, the “Farm Colony” was established to provide employment and agricultural training. Third, the “Oversea Colony” involved securing “millions of acres of useful land to be obtained almost for the asking, capable of supporting our surplus population in health and comfort.”

Though the third scheme was never fully realized, it had a profound impact on the development of the Army in Canada and helped shape the nation. In 1905, the SS Vancouver, the first migrant ship chartered by the Army, departed the shores of Liverpool, England, with 1,000 passengers bound for Canada. Over the next four decades, 250,000 immigrants including men, women, boys, girls, families and widows with children from the United Kingdom, travelled in liners supervised by Army personnel and were helped to settle into a new land, with a new home and often a new family. Pioneer communities such as Coombs, B.C. (named after the territorial commander of Canada at the time), were established and still exist today. Thousands of Canadians can trace their roots to the massive immigration program that found its birth in The Darkest England plan to alleviate the lot of Britain’s poor in the late 19th century.

One hundred and thirty years later, we can still thoughtfully reflect on the book’s contemporary message. According to the most recent STATSCAN report, 3.2 million Canadians (8.7 percent), including over 560,000 children, live in poverty, and depending on the formula used to define it, that number could rise to four million. We have our own “submerged tenth” right here in our own nation. Many of the core issues addressed in The Darkest England scheme remain at the heart of our social reality in Canada—poverty, addiction, social injustice, human trafficking and homelessness, to name just a few. Though methods and language change, this century-old book still has a profound message for the Army in this time. May it be a continued call to action as we exercise the mission—Giving Hope Today!

“When but a mere child the degradation and helpless misery of the poor Stockingers of my native town, wandering gaunt and hunger-stricken through the streets droning out their melancholy ditties, crowding the Union or toiling like galley slaves on relief works for a bare subsistence kindled in my heart yearnings to help the poor which have continued to this day and which have had a powerful influence on my whole life.”

In Darkest England, And the Way Out was crafted by Booth as a graphic response to the appalling social conditions in Victorian England and based on the theological foundation that shaped his life. Having trained as a Methodist preacher, Booth’s heart was gripped by the theology of John Wesley who stated, “The gospel of Christ knows no religion but social; no holiness but social holiness.” For Booth, doctrine could never be perceived in isolation from the reality of human life and theology could never be divorced from the human condition. Authentic faith for him meant to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, house the homeless, liberate those enslaved by addiction and prostitution, bring comfort to the lonely, care for the sick, minister to the imprisoned and provide a better life in the here and now, as well as in the hereafter.

By the time the book was published in 1890, The Salvation Army, established in 1865, had expanded its operations to 26 countries on six continents around the globe. This influential book sold 115,000 copies within the first three months, and more than 300,000 copies within its first year of publication.

Booth estimated that 10 percent of the population of Great Britain at that time, about three million people, were living in abject poverty. In the Cab-Horse Charter, he contended that any cab horse in London (the Uber of the day) was blessed with a better life than human beings who fell within this “submerged tenth.” The two points that defined the life of a cab horse was that when he was down, he was helped up and while he lived, he had food, shelter and work. “That, although a humble standard, is at present unattainable by millions—literally millions—of our fellow men and women in this country,” he wrote.

Booth articulated a three-phase scheme to provide “hope for all” suffering from homelessness, poverty and unemployment. First, the “City Colony” phase established “Harbours of Refuge,” which were designed to bring relief to the crippling overcrowding in the urban centers. Second, the “Farm Colony” was established to provide employment and agricultural training. Third, the “Oversea Colony” involved securing “millions of acres of useful land to be obtained almost for the asking, capable of supporting our surplus population in health and comfort.”

Though the third scheme was never fully realized, it had a profound impact on the development of the Army in Canada and helped shape the nation. In 1905, the SS Vancouver, the first migrant ship chartered by the Army, departed the shores of Liverpool, England, with 1,000 passengers bound for Canada. Over the next four decades, 250,000 immigrants including men, women, boys, girls, families and widows with children from the United Kingdom, travelled in liners supervised by Army personnel and were helped to settle into a new land, with a new home and often a new family. Pioneer communities such as Coombs, B.C. (named after the territorial commander of Canada at the time), were established and still exist today. Thousands of Canadians can trace their roots to the massive immigration program that found its birth in The Darkest England plan to alleviate the lot of Britain’s poor in the late 19th century.

One hundred and thirty years later, we can still thoughtfully reflect on the book’s contemporary message. According to the most recent STATSCAN report, 3.2 million Canadians (8.7 percent), including over 560,000 children, live in poverty, and depending on the formula used to define it, that number could rise to four million. We have our own “submerged tenth” right here in our own nation. Many of the core issues addressed in The Darkest England scheme remain at the heart of our social reality in Canada—poverty, addiction, social injustice, human trafficking and homelessness, to name just a few. Though methods and language change, this century-old book still has a profound message for the Army in this time. May it be a continued call to action as we exercise the mission—Giving Hope Today!

Comment

On Wednesday, October 14, 2020, Kevin Saylor said:

Leave a Comment