But just before nine o’clock, a tragic navigation error resulted in a collision between the Mont Blanc—a French munitions ship loaded with 2,300 tons of piric acid, 225 tons of TNT and a deckload of benzene—and the Imo, a Belgian relief ship.

It was the greatest pre-atomic explosion the world had known to that date. In a split second, the Mont Blanc vanished in a mushroom of flaming gases that reached more than a kilometre into the air. The outward blast of air and the subsequent tsunami levelled everything within a one-and-a-half-kilometre radius. Homes, offices, shops, churches and warehouses were either obliterated by the blast or destroyed by the fires started by overturned stoves. Approximately 2,000 Haligonians either died instantly or later of their injuries, as many as 9,000 others suffered a multitude of injuries (more than 200 of them having been blinded by flying glass) and as many as 20,000 were left homeless.

One Family’s Disaster

Among the dead and injured was a Salvation Army family, Ensign Cranwell, his wife and baby daughter.

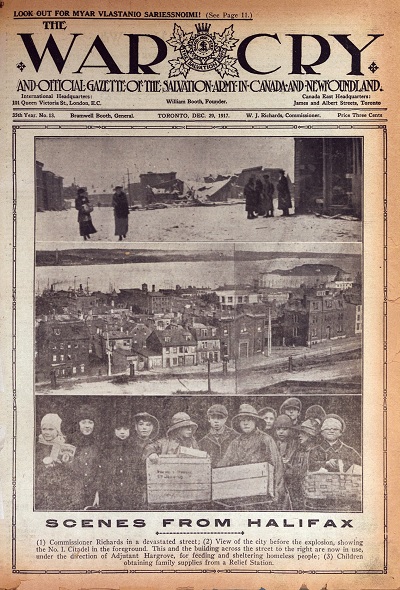

Readers of The War Cry stayed up-to-date with the tragic events in Halifax

Readers of The War Cry stayed up-to-date with the tragic events in Halifax

“Getting no answer, I went back to the dining room and was horrified to see Mrs. Cranwell bleeding severely from many wounds. She had the baby in her arms, and I heard afterwards from others who were in the house that her first words were, ‘Where’s my baby?’ She rushed to pick the little one up. She was uninjured, though the feeding bottle had been blown from its mouth.

“Seeing that Mrs. Cranwell was severely hurt, I rushed out to find a doctor. Immediately on gaining the street, I realized something of the extent of the disaster. A terrible scene of devastation met my eye in every direction, and people were frantically rushing about uttering pitiful cries. I failed to secure a doctor, and returned to the house just as Mrs. Cranwell was breathing her last. To friends around her she said: ‘Is the Ensign safe? Is the baby alright? Oh, I’m choking!’ ”

Even though his heart must have been breaking, once he was certain his wife was dead, Cranwell put his own grief aside and, leaving his daughter with friends, rushed off through the debris-strewn streets, to see if other Salvation Army officers in Halifax were safe.

Territorial Response

The immediate acts of rescue came from people just like Ensign Cranwell—as a responsive action so typical of human beings in disaster situations. After this, the city’s police, firefighters and soldiers began a more organized rescue, taking the injured to hospital or first-aid units or to hastily established shelters in the YMCA, the Salvation Army citadel and even the jail. And, finally, before the day was over, aid—medical teams, rescue workers, money, food and supplies—began pouring in from across the country and eventually from all over the world.

Among the first of these were Salvation Army officers from Atlantic Canada, to supplement and direct the rescue operations already being engaged in by the Salvationists of Halifax. By a stroke of good fortune, the territorial commander, Commissioner William Richards, and his chief secretary, John McMillan, were in the area conducting revival meetings. They proceeded immediately to the disaster area, being among the first to enter the stricken city, and promptly began to assist Adjutant Hurd and 13 local Salvation Army soldiers with the distribution of food to the disaster victims. All, regardless of rank, took their turn at bagging bread, biscuits, tea, coffee and other food staples that were being given to all those in need.

Ensign Ham, also one of the first officers to reach Halifax, was given charge of the “free coal” depot. All applications were referred to him and, when necessary, he ordered coal to be supplied by a local firm. The blizzard that descended on the city immediately following the disaster made this a crucially important assignment.

Answering the Call

Within a matter of days, Salvation Army officers from Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Ontario were ordered to Halifax to assist with the rescue operations, which were to last for months. In addition to providing for the practical needs of those impacted, such as food and clothing, Salvation Army officers provided emotional and spiritual support to responders.

The Salvation Army set up teams to serve meals in shelters and do other volunteer work as needed. One Army ensign even found himself assisting in a hospital operating room. Dozens of other Salvationists performed heroic service in one of the largest rescue operations in Canadian history.

And when Christmas came around, The Salvation Army’s usual Christmas programs were considerably extended to take account of the increased need.

The Army’s efforts were not unappreciated. “We do not know how we would have gotten along without them,” wrote R.T. MacIlreith, the chairman of the relief committee, to The War Cry.

The Salvation Army’s prompt response to the Halifax disaster marked an important milestone for the church and the birth of the emergency disaster services (EDS) in Canada. It was yet another way that the Army could give practical expression to its Christian mandate by responding to local and national emergencies as a partner in the subsequent rescue efforts. In any of the many large and small disasters in Canadian history that followed, the EDS would become a distinctive feature of its community outreach.

Salvation Army historian Dr. R. Gordon Moyles is the author of The Blood and Fire in Canada: A History of The Salvation Army and the forthcoming Across an Ocean and a Continent: The Salvation Army as a Canadian Immigration Agency 1904-1932, available at store.salvationarmy.ca.

Comment

On Wednesday, November 3, 2021, Rick Cranwell said:

On Tuesday, December 8, 2020, Rob Jeffery said:

On Monday, December 11, 2017, lorena herridge said:

Leave a Comment