The conversation is still fresh in my mind, almost as if it took place yesterday. I sat in then Commissioner Clarence Wiseman’s office in Toronto and we talked about Salvation Army officership. I wanted to explore possible ways to engage in Salvationist ministry, but without becoming an officer. I didn’t want to be bound by the requirements of officership. And I couldn’t see myself living the life of a cadet. There was good give-and-take in the conversation. Finally, this gracious leader looked me in the eye and said, “Ray, I think your best contribution to The Salvation Army will be as an officer.” Fifty years later, I still find myself thinking about that conversation.

It wouldn’t surprise me if Salvationists across the territory are having the same conversation—with others, if not with themselves— today: What is the point of becoming an officer when I can serve the Army in other ways? Do I want to limit my freedom with respect to the places I serve, or the ways I serve? Do I want to place the life of my family at the mercy of decisions made by others? These are important questions to be asking. However, from the vantage point of living with them for 50 years, I would like to offer a personal response.

Tradition!

The word “ordination” means to place a person under orders by the church. However, that idea meets with strong resistance in our culture. The church, let alone the Christian faith, is under deep suspicion in this nation. Perhaps it’s because of this that I increasingly value the concept. As is true with many concepts, we learn their meaning by living them out. The meaning of ordination is something I have learned by living out my identity as a Salvation Army officer.

Ordination has come to help me understand the importance of tradition. For our first date in 1972, I took Cathie, now my wife, to see the film, Fiddler on the Roof. If you have seen the film you will recall one of its signature songs, Tradition! Like Tevye, the main character, and his daughters, 50 years ago I questioned the role of tradition within The Salvation Army. Over time, however, I have come to learn its importance. When the Winnipeg Jets step on the ice to play the Edmonton Oilers, they play the game out of its tradition, its embodied story. Past teams and players, changes in equipment, the ’72 Summit—all form the story, the tradition, of hockey. Any game played today expresses that tradition and leads to its ongoing life. Law is practised within a tradition, as is medicine. A Salvation Army officer is shaped by many traditions—above all, the tradition of the gospel as it has come to be embodied within The Salvation Army. This doesn’t mean simply repeating what has been done in the past; it does mean critically carrying the Army’s embodied story forward into our own culture.

Living under orders has meant learning to live in places I would not have chosen. I grew up in Hamilton, Ont., but began the journey of officership by living in Toronto. And, yes, I really did come to appreciate the capital of Ontario. Our appointments took us to the Prairies, where we came to appreciate their beauty and the hard work of farming. But moving to new appointments has not been without tears. We were appointed to Fort McMurray, Alta., soon after my father had suffered his second heart attack. I felt the distance. And it wasn’t easy leaving two young adult children in Toronto to continue their studies.

There has, however, been another side to this aspect of living under orders. Our last appointment, in St. John’s, N.L., was completely unexpected. We came to embrace the hospitality of Newfoundlanders, even if it meant kissing the cod! A few years ago, Cathie and I were in New York City when we learned that the musical, Come From Away, had just opened on Broadway. This musical portrays Newfoundland’s response to the diversion of planes because of 9/11. As we took in the performance, we sensed the audience’s enthusiastic response. Americans sitting beside us thanked us profusely. I don’t think my Newfoundland friends will mind knowing that we acknowledged the gratitude of Americans. Because of Salvation Army appointments, I have come to a deep appreciation and love for Canada. It’s a nation living with deep tensions, but I am committed to its life together. The appointment system has helped to shape my understanding of Canada.

Core Convictions

One of the important dimensions of officership for me has been the Army’s core convictions, its doctrines. When cadets are ordained and commissioned, the Affirmation of Doctrines is an essential part of the service. After affirming these core convictions, cadets are asked by the presiding officer if they will faithfully teach these doctrines. Binding ourselves to believe certain convictions is deeply countercultural—surely we are free to believe what we want to believe. At some level, yes, we are. But what I have learned over the years is that Salvation Army doctrines have grounded me in the deepest convictions of the historic church. The early church created brief summaries of faith, called “ruled faith.”

Interesting things happen when a grandfather watches his grandson move through different levels of hockey. As the kids age, the rules change and the game changes. The rules are not the game, but they shape the game being played. Our Salvationist convictions shape the game we play, or at least they should. My plea is for a new generation of Salvationists, of ordained officers, who will take our core convictions and ask how they shape our response to climate change, racial hatred, refugees and the care of our cities and nation. Let’s imagine the ways that our mission is shaped by our core convictions.

A Covenantal Community

Living under the orders of ordination has gifted me with a covenantal community. When we moved into the Toronto College for Officer Training as cadets in 1972, Cathie and I gained new neighbours. She never imagined having to study in our small one-room apartment while I had some of the guys in to watch a game of the Canada-Russia Summit Series. Over the years, this officer community has taken on a life of its own for me. We have mourned the losses affecting colleagues; we have cheered their accomplishments and encouraged those who lost heart; and we have shared hopes and frustrations.

One aspect of officership I have come to appreciate over the years is the Army’s approach to remuneration. As an officer, I do not negotiate remuneration. Whatever our level of education and responsibility of our appointments, officers are remunerated on the basis of length of service, not academic or professional credentials. And I appreciate this. The relationship of an officer to The Salvation Army is covenantal, not contractual. In his book, The Dignity of Difference, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks expresses the importance of covenant this way: “Covenant is an answer to the most fundamental question in the evolution of societies: How can we establish relationships secure enough to become the basis of co-operation, without the use of economic, political or military power?” The covenant of Salvation Army officership holds implications for the life of our nation.

Embracing Limitations

Yes, ordination and commissioning involve important limitations to what I wear, where I live and what I think. But during these 50 years, I have come to more fully understand that the God we know through Christ is the God who embraced limitations to accomplish our immense salvation. This is the thrust of Paul’s argument in his letter to the Philippians, when he unpacks his understanding of the mind of Christ, “who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave” (Philippians 2:6-7 NRSV, emphasis mine). The word “emptied” means that God-in-Christ placed limitations on himself to achieve his saving purposes. The degree to which officership involves limitations only resonates with our deep convictions about the God we know through Christ.

When I entered the College for Officer Training 50 years ago, I had little idea of the journey that lay ahead. I am grateful for the patience my colleagues have had with me. I am grateful for the opportunities to engage in formal studies over the years. I am grateful for the trust placed in me by supervising officers. And I am deeply grateful for Cathie, with whom the covenant of marriage has informed my covenant of officership. I have yet to “finish the race,” but I sometimes imagine the moment when Clarence Wiseman and Ray Harris stand face to face again. And I can see this gracious man looking me in the eye with a gentle smile and saying, “Ray, I told you so.” I have a hunch he will be right.

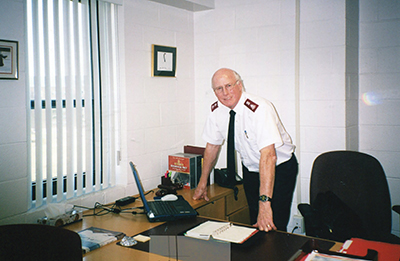

Major Ray Harris is a retired Salvation Army officer who lives in Winnipeg.

This story is from:

Comment

On Monday, May 15, 2023, Cavell Loveless said:

On Thursday, May 11, 2023, Robert Burrell said:

As an officer over the years you build many relationships. Some end up influencing your beliefs and subsequent behaviour /decisions. Major Ray, you and Cathie have blessed our family with a unique combination of integrity and grace. I am thankful that you made that decision to pursue officership.

On Thursday, May 11, 2023, Charlotte Dean said:

Leave a Comment