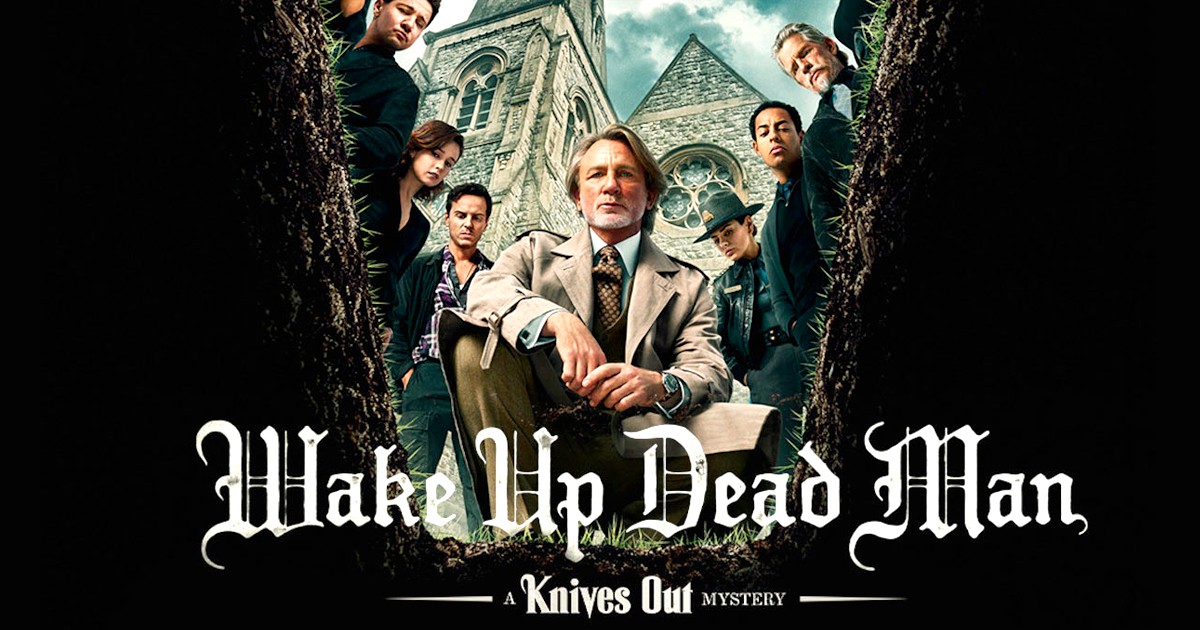

I love a mystery. I grew up loving stories from Agatha Christie, Edgar Allan Poe and others, and I feel at my coziest watching (or re-watching) a good whodunnit. Wake Up Dead Man, the latest in the Knives Out franchise, did not disappoint.

At its heart, Wake Up Dead Man is a locked-door mystery about a church that has adopted a posture of defensiveness, shutting out those it doesn’t understand in favour of protecting a group of faithful, yet closed-off, congregants who are terrified of the world. But that’s not the whole story.

The film’s protagonist is Father Jud, a former boxer who joined the priesthood after killing a man in the ring. Jud is utterly, unabashedly human. He lives with his mistakes while tethering himself to grace, which he seeks to extend to whomever needs it.

After an altercation with a deacon, Jud is moved to Chimney Rock to work under Monsignor Jefferson Wicks. While Wicks’ grandfather began the parish, choosing the pursuit of holiness and community over the fortune that had divided his family, Wicks sees the church and the world as adversaries. He prides himself on shaming single mothers, queer couples and any others he can bludgeon with righteous vengeance.

“You start fighting wolves, and, before you know it, everyone you don’t understand is a wolf.”

Surrounding Wicks is his small congregation, led by Martha, a life-long attendee, and Samson, the groundskeeper. Other core congregants include Vera, who resents sacrificing her own happiness to make her father proud; Cy, Vera’s half-brother who constantly drums up online outrage in search of political power; Lee, a science-fiction writer who is becoming increasingly bitter and paranoid about the world; Nat, an alcoholic doctor whose wife has left him; and Simone, a woman with chronic pain who has put her trust and her savings into Wicks’ promise of healing.

After a particularly fiery sermon one Good Friday, Wicks steps down from the pulpit and collapses in a closet with a knife in his back. The murder is impossible and, rocked with the news of Wicks’ death, the community sees Father Jud as the chief suspect. Luckily, famed private detective Benoit Blanc is on the case to solve the mystery.

While the plot is full of twists and turns, as any good mystery is, the film’s depiction of how the church and the concept of grace can easily grow apart reminds us that Christianity was built on love, not judgment.

In the beginning, Jud sits before a disciplinary committee, where a priest claims that we need “to fight the world, not ourselves” and calls the world “a wolf.”

Later, when he walks into Wicks’ church, Jud notices a void where the cross should be. When he offers to replace it, Wicks calls the empty space a reminder of the “shameful sin of the harlot whore,” referring to Grace, his single mother who was so desperate to find the family fortune the elder Wicks hid that she flew into “a demonic rage.”

Rather than see the cross as a symbol of hope in a world that creates such desperation, Wicks has chosen to see it as a symbol of his mother’s sin and a testament to his (and God’s) unforgiveness.

Wicks’ congregants are similarly broken: Martha revels in “holy” exclusivity. Cy uses the Bible to support his hateful, xenophobic ramblings. Lee builds a moat around his house.

Everyone in the congregation uses faith to fuel their fears of others and of irrelevance, and to justify an agenda of exclusion. We see this in our world, too.

We see well-meaning people convince themselves that the church is always good, and the world is always bad. That God’s wrath only comes to those outside the church’s “protection.” That “knowing” what’s right gives us a free pass to judge others.

The sentiment that the church should gird its loins from the big, bad world is all too familiar in the culture wars that currently plague us. But, in one of many poignant lines throughout the film, Jud offers another point of view: “You start fighting wolves,” he says, “and, before you know it, everyone you don’t understand is a wolf.” He then spreads his arms wide, as a crucifix depicts Christ, and says, “This, not this,” as he puts up his dukes.

Wake Up Dead Man reminds us that “Christ came to heal the world, not fight it,” as Jud says. Sometimes Christians do bad things in the name of Christ. Sometimes the seemingly undeserving experience grace and are eager to bestow it on others.

Like the U2 song of the same name, Wake Up Dead Man urges us to “listen over” the noise that keeps us from the work of love. It doesn’t condemn the church. It encourages it to wake up and do better.

Dr. Mandy Elliott is an assistant professor of English and film studies at Booth University College in Winnipeg.

Wake up Dead Man is available on Netflix.

Photos: Courtesy of Netflix

Leave a Comment