Since it was established, the commission has hosted seven truth and reconciliation events across Canada. The last of these events was held in Edmonton on March 27-30, 2014, and was attended by Captain Shari Russell, territorial Aboriginal liaison. Below, Captain Russell reflects on her experiences at the TRC event and what reconciliation means for Canadians and for the church.

***

“It would be so much easier just to fold our hands and not make this fight … to say, I, one man, I can do nothing. I grow afraid only when I see people thinking and acting like this. We all know the story about the man who sat beside the trail too long, and then it grew over and he could never find his way again. We can never forget what has happened, but we cannot go back nor can we just sit beside the trail.”

—Petocahhanawawin (Chief Poundmaker), 1842-1886, his dying words

The impact of the Indian Residential Schools (IRS) is an intergenerational trauma. Over the course of 130 years, approximately 150,000 Indigenous children were forced to attend these church-run schools, irrespective of their parents' wishes. Many of them were subject to severe physical, emotional and sexual abuse, as well as cultural genocide. To think that this could happen in our country—to grapple with the fact that the last residential school closed in 1996—is inconceivable, and yet it is reality. Whether from the perspective of the offender or survivor, the legacy of the IRS is a colossal chasm that has shaken the foundation of our nation.

It would be much easier to recount the facts about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) than to articulate the profound personal impact of the TRC on the participant. Attending the TRC event in Edmonton was a personal journey for me, as my sisters attended a residential school. It was also significant for me as territorial Aboriginal liaison because it is imperative that the church is present at such events so that we learn from our history and ensure that this will never happen again.

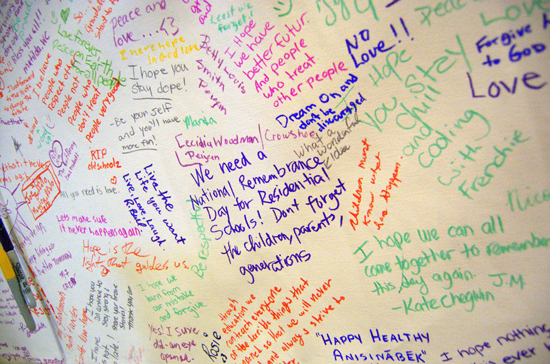

Participants share messages of hope at the TRC event in Edmonton (Photo: Anglican Church of Canada)

Participants share messages of hope at the TRC event in Edmonton (Photo: Anglican Church of Canada)

Restoring Dignity

The focus of the event in Edmonton was wisdom, one of the Seven Sacred Teachings of the Indigenous People. It was a fitting theme as we have learned truth concerning the residential schools and now must endeavour to respond accordingly.

As I walked down the stairs of the conference centre, it was a physical reminder of Mother Earth (the dust) from which we were all formed. It is with this humility, recognizing that we are equal in God's sight, that we can begin to forge respectful relationships as we courageously hear the truth of our history and journey together toward reconciliation.

Honour and dignity were established at the onset. The opening ceremonies began with the entry of the Eagle Staffs (Aboriginal flags), followed by the commissioners, honorary witnesses and dancers. As the Eagle Staff entered, a realization rose within me that this may have been the first time survivors had seen the Eagle Staff and dancers together with church representatives.

When Justice Murray Sinclair, chair of the TRC, asked the survivors to stand, there was a powerful recognition that they were not alone. As they stood together, a silent strength came over the survivors and their families, and a deep bond was formed.

The families of survivors were invited to stand in solidarity with them and in recognition of the schools' intergenerational impact. As I stood in recognition of the impact on my family, I was thankful for my sisters' strength, resilience and courage in sharing their stories and overcoming the challenges they encountered in life.

Magnitude of Loss

Throughout the event, survivors were given the opportunity to share their stories. Many people were impacted emotionally as they listened to the survivors. Strong men sobbed uncontrollably and women vented deep-seated anger. Tears flowed as children heard their parents' stories and mothers wept upon hearing how their experience with the IRS had harmed their children. Here, the intergenerational impact of the IRS was clear: because of the trauma they had experienced, the parents could not show their children affection or love in healthy ways, and the children felt disconnected from their own culture.

As I sat cross-legged on the floor of a small, jam-packed room listening to survivors, my sisters' stories echoed in my mind. The legacy of families torn apart, of children and parents never seeing each other again, permeated every story. One woman in a sharing circle, overcome with immense grief, sobbed: “I lost my mother, my father, my sisters, I lost them all … I am so disconnected from myself. I am ashamed to be an Indian woman.” Many others also shared their compounded loss: the loss of family, community, home, language, identity and culture. I was thankful for the house support personnel who were attentive to the moments of the heart and gently collected tear-filled tissues, which were later incorporated into a healing ceremony.

Importance of Awareness

Cpt Shari Russell (left) attends the TRC event in Edmonton with friend, Alison LeFebvre

Cpt Shari Russell (left) attends the TRC event in Edmonton with friend, Alison LeFebvre

On the first day of the event, junior and senior high school students were invited to attend and learn about the impact of the IRS. Seeing them fill the auditorium highlighted the importance of educating our children to ensure we learn from this dark chapter of Canadian history.

Many people have been reticent about the TRC. Even the name may be upsetting: “truth” and “reconciliation” are uncomfortable words for us. Part of the struggle is that we do not know our history. Even survivors of the residential schools did not realize the scope of the abuse that took place. They often thought they were alone in the experience.

And the IRS are not the only recent attempt at forced assimilation. Approximately 20,000 Aboriginal children were fostered by child welfare between the 1960s and late 1980s, in what is known as the Sixties Scoop. The effects of the Scoop continue today in the significant overrepresentation of Aboriginal children in the child welfare system. The impact of this part of our history was also discussed at the TRC event.

The purpose of sharing our collective story through the TRC is not to hurt or punish non-Aboriginal people or incite guilt, but to seek recognition of the truth.

Current Attitudes

As we listened to various presentations, it was acknowledged that there are still some attitudes within Canadian culture that affect First Nations today. They include:

Indifference: The value and importance of the TRC events have not affected us on a level where we strongly encourage attendance, education or advocacy in the appeal for justice.

Ignorance: Many Canadians remain unaware of the legacy of the IRS.

Arrogance: As Canadians, we have a positive reputation for altruism and humanitarian action. However, this may lead us to think that we are always "doing it right."

Frustration: The fact that the last school closed in 1996 shows that it is not so ancient.

Guilt: Some people recognize the atrocities committed and find it difficult and unreasonable to be held accountable for something they themselves did not actively participate in.

Misconceptions: The challenges of prejudice and racism persist today.

The Meaning of Reconciliation

Once the truth is shared and acknowledged, then reconciliation is possible. Reconciliation is not about “making it go away”—nor is it about “making it right,” as Aboriginal people know that is impossible.

For survivors, reconciliation means reconciling the hate, anger, loneliness, loss, abuse, coping methods and the impact on subsequent generations. For non-Indigenous people, it includes reconciling the pain and injustice done, the prejudice and systemic racism, the good intentions and the inability to “fix” it. Then we can reconcile with one another as we listen to the stories, learn from one another, honour one another with grace and humility, share our gifts and, especially, as we commit to never let this happen again.

At the Edmonton event, I was profoundly impacted by a presentation from Éloge Butera, a survivor of the Rwandan genocide, and Robbie Waisman, a survivor of the Buchenwald concentration camp. Quoting James Baldwin, they said, “The moment we cease to hold each other, the moment we break faith with one another, the sea engulfs us and the light goes out.”

Reconciliation involves everyone. Although we may not be personally liable for the injustices of the past, when we remain silent, we have ceased to be engaged in the reconciliation process. As Christians—as The Salvation Army—we are called to be ministers of reconciliation.

Reconciliation begins with me. The TRC event finished with a walk to the legislature. As we walked the diverse group began to walk in unity. A woman started drumming and singing. Two others joined in. As their voices rose, I recognized the song and I, too, began to sing. Reconciliation means not only walking on the same road toward the same goal; it means sharing together on that road, engaging with those beside us, lifting our voices in harmony, respecting one another's differences and celebrating our commonality. Reconciliation means that we will not sit by the road, but will walk together as we forge the trail with genuine relationships.

Captain Shari Russell is the territorial Aboriginal liaison and corps officer at Sudbury Community Church, Ont.

Thank you for sharing this and the fact you are residing in Bermuda. As Territorial Aboriginal Consultant, I am attempting to put together a picture of First Nations people within The Salvation Army. I would love to connect with you at some point. There are a few First Nations people serving as Officers and lay leaders and I am praying these numbers will continue to grow.