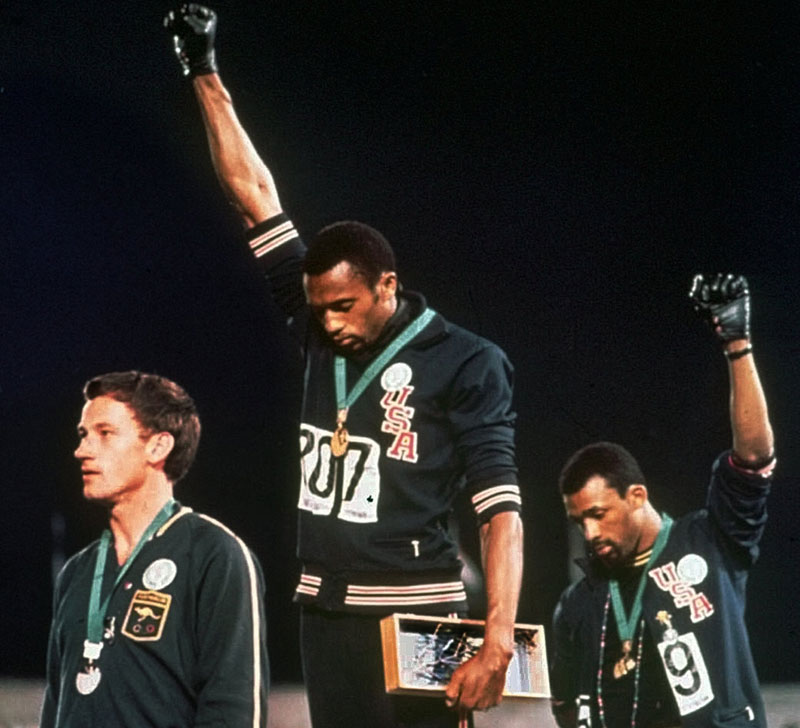

(Above) U.S. athletes Tommie Smith, centre, and John Carlos raise black-gloved fists skyward during the medal ceremony for the 200-metre race at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City. Peter Norman, the Australian Salvationist who won the silver medal, supported the civil rights protest (Photo: © ASSOCIATED PRESS)

In 1968, racial and political tensions in the United States had peaked. In April, James Earl Ray took the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., in Memphis, Tenn. Two months later, Sirhan Sirhan shot and killed Senator Robert F. Kennedy in Los Angeles. And in October at the Summer Olympics in Mexico City, three track runners stood on the winners’ podium to advocate for human rights and for social justice.

The names of the gold and bronze medalists, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, became well known. But the silver medalist, Peter Norman, who was also a Salvationist, has only recently gained public attention.

Photos of the award ceremony show Smith and Carlos with their heads bowed and their black-gloved fists held high as musicians played the Star Spangled Banner. Each also wore an “Olympic Project for Human Rights” badge.

Peter Norman, the Australian sprinter who came in second in the 200-metre race, borrowed a badge from U.S. rowing champion Paul Hoffman and wore it during the medal ceremony. And because Smith and Carlos had brought only one pair of black gloves, Norman had suggested that Carlos and Smith wear one glove each.

Carlos asked Norman, “Do you believe in human rights?” Norman said, “Yes.” Smith asked, “You’re in The Salvation Army. Do you believe in God?” Norman, who grew up in a devoted Salvation Army family, came from Coburg, a suburb of Melbourne in Victoria, Australia, and was educated there at The Southport School. He said, “I believe strongly in God.”

Years later, Carlos remembered, “We knew that what we were going to do was far greater than any athletic feat, yet Norman said, ‘I’ll stand with you.’ I expected to see fear in Norman’s eyes, but instead we saw love.”

For their actions, Smith and Carlos were suspended from the U.S. team by the International Olympic Committee and banned from the Olympic Village and from the games—for life. Norman’s actions resulted in his being ostracized by Australian media and reprimanded by his country’s Olympic authorities, who did not send him or any other male sprinters to the 1972 games, despite their having all easily qualified.

When Australia hosted the 2000 Summer Olympics, Norman was excluded from participating with other Australian medalists during the opening ceremony.

In 2005, San José State University officials placed on its grounds a statue commemorating the 1968 Mexico Olympic Games’ greatest moment, “The Black Power Salute.” Tommie Smith’s image was there on the gold medal podium, John Carlos’ statue was there on the bronze medal podium, but for Peter Norman, the silver medalist, the second-place winner’s spot on the podium remained empty of a statue.

But at the unveiling ceremony, Norman paid tribute to his dear friends. “They deliberately gave away their personal glory as a privilege,” he said.

In 2006, Norman died of a heart attack. Smith and Carlos, who had become his life-long friends, offered eulogies to their “brother” and served as pallbearers.

To see a trailer for a documentary on Peter Norman produced by his nephew, Matthew Norman, click here: “Salute.”

Reprinted from SAconnects magazine, January/February 2016.

Leave a Comment