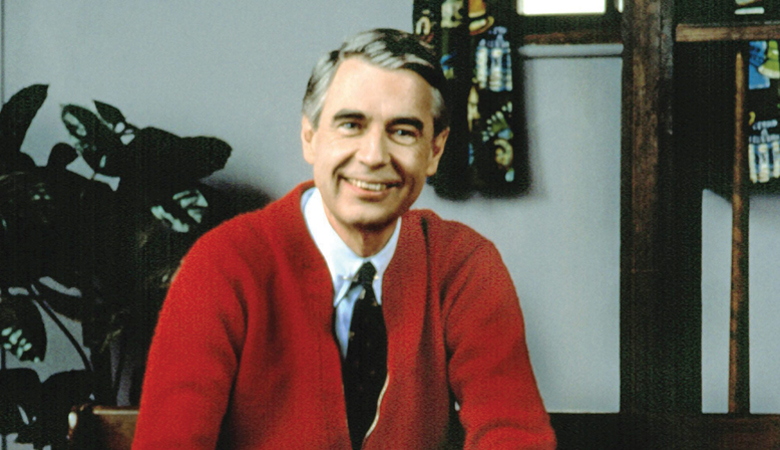

(Above) Fred Rogers’ series originated on CBC television in 1962

A number of months ago, I read an op-ed article in the Toronto Star written by a young man who came to Toronto from China to complete his graduate studies. The article was entitled, “Canadians are nice and polite. Maybe that’s why it’s so hard to make friends here.” I was intrigued.

From his experience, “smiles and cordiality—often masking indifference and distance—are no recipe for forging meaningful connections. Niceness, or politeness, seems to breed transient relationships. Canada’s signature openness and multiculturalism are very much the by-products of its niceness. But beneath it lurks the lesserknown side of the Canadian etiquette, one that seems steeped in aloofness and reservation and most pronounced at the personal level.” He supports his observation with two recent Canadian studies: a 2018 study from the University of British Columbia, which found that Toronto and Montreal were the least-happy cities in Canada, with low levels of community belonging; and a 2017 survey by the Vancouver Foundation, which revealed that a third of Vancouverites between the ages of 18 and 24 experience loneliness “almost always” or “often.”

Shortly after reading this article, my attention was drawn to the books, documentary and new movie released to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Fred Rogers, the creator of the PBS broadcast, had an acute understanding of our common need for relationship, acceptance and belonging. He believed that one of the greatest gifts we can give to each other is the gift of time. He intentionally opened each show with deliberate acts that altered the pace, changing from his jacket to a comfortable sweater and from dress shoes to running shoes. Without words and through simple acts, he let each child watching know that he valued his time with them enough to step away from the distractions of the day to be present with them. As you listen to the reflections of those who knew him well, this was his gift not only to children, but to everyone he encountered.

His second gift to others was his vulnerability. “I just figured that the best gift you could offer anybody is your honest self, and that’s what I’ve done for lots of years,” he is quoted in The Simple Faith of Mister Rogers by Amy Hollingsworth.

He was a man of faith who carefully attended to the inner life. His engagement with others reflected his personal relationship with his heavenly Father. He shared the love and acceptance he received from God with all those he encountered. In The Screwtape Letters, C.S. Lewis wrote, “When Christians are wholly his, they will be more themselves than ever.” When our inner life is deeply rooted, we can be open with our vulnerability.

Rogers trusted that “what is offered in faith by one person can be translated by the Holy Spirit into what the other person needs to hear and see,” writes Hollingsworth. “The space between them is holy ground, and the Holy Spirit uses that space in ways that not only translate, but transcend.” Before entering the studio each day, he prayed, “Dear God, let some word that is heard be yours.”

Rogers truly was a “good neighbour.” He was a living example of 1 Peter 4, with respect to community: “Be earnest, thoughtful [people] of prayer. Most important of all, show deep love for each other, for love makes up for many of your faults. Cheerfully share your home with those who need a meal or a place to stay for the night. God has given each of you special abilities; be sure to use them to help each other, passing on to others God’s many kinds of blessings” (1 Peter 4:7-10 TLB).

The young Star contributor ended his article with this: “I’m still learning and adapting, mindful that the transition to any new culture takes time. And that building social ties from scratch takes effort. Though sometimes I wish Canadians were less ‘nice’ and more willing to share and open their hearts.”

As we strive to cultivate a community of shalom—of wholeness and flourishing—within our organization, one in which we believe the best in each other, want the best for each other and expect the best from each other, may we be quick to be good neighbours, sharing the gifts of time and vulnerability. May the space between us be holy ground rather than lonely ground.

Lt-Colonel Brian Armstrong is the secretary for personnel.

Photo: © The Canadian Press

A number of months ago, I read an op-ed article in the Toronto Star written by a young man who came to Toronto from China to complete his graduate studies. The article was entitled, “Canadians are nice and polite. Maybe that’s why it’s so hard to make friends here.” I was intrigued.

From his experience, “smiles and cordiality—often masking indifference and distance—are no recipe for forging meaningful connections. Niceness, or politeness, seems to breed transient relationships. Canada’s signature openness and multiculturalism are very much the by-products of its niceness. But beneath it lurks the lesserknown side of the Canadian etiquette, one that seems steeped in aloofness and reservation and most pronounced at the personal level.” He supports his observation with two recent Canadian studies: a 2018 study from the University of British Columbia, which found that Toronto and Montreal were the least-happy cities in Canada, with low levels of community belonging; and a 2017 survey by the Vancouver Foundation, which revealed that a third of Vancouverites between the ages of 18 and 24 experience loneliness “almost always” or “often.”

Shortly after reading this article, my attention was drawn to the books, documentary and new movie released to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Fred Rogers, the creator of the PBS broadcast, had an acute understanding of our common need for relationship, acceptance and belonging. He believed that one of the greatest gifts we can give to each other is the gift of time. He intentionally opened each show with deliberate acts that altered the pace, changing from his jacket to a comfortable sweater and from dress shoes to running shoes. Without words and through simple acts, he let each child watching know that he valued his time with them enough to step away from the distractions of the day to be present with them. As you listen to the reflections of those who knew him well, this was his gift not only to children, but to everyone he encountered.

His second gift to others was his vulnerability. “I just figured that the best gift you could offer anybody is your honest self, and that’s what I’ve done for lots of years,” he is quoted in The Simple Faith of Mister Rogers by Amy Hollingsworth.

He was a man of faith who carefully attended to the inner life. His engagement with others reflected his personal relationship with his heavenly Father. He shared the love and acceptance he received from God with all those he encountered. In The Screwtape Letters, C.S. Lewis wrote, “When Christians are wholly his, they will be more themselves than ever.” When our inner life is deeply rooted, we can be open with our vulnerability.

Rogers trusted that “what is offered in faith by one person can be translated by the Holy Spirit into what the other person needs to hear and see,” writes Hollingsworth. “The space between them is holy ground, and the Holy Spirit uses that space in ways that not only translate, but transcend.” Before entering the studio each day, he prayed, “Dear God, let some word that is heard be yours.”

Rogers truly was a “good neighbour.” He was a living example of 1 Peter 4, with respect to community: “Be earnest, thoughtful [people] of prayer. Most important of all, show deep love for each other, for love makes up for many of your faults. Cheerfully share your home with those who need a meal or a place to stay for the night. God has given each of you special abilities; be sure to use them to help each other, passing on to others God’s many kinds of blessings” (1 Peter 4:7-10 TLB).

The young Star contributor ended his article with this: “I’m still learning and adapting, mindful that the transition to any new culture takes time. And that building social ties from scratch takes effort. Though sometimes I wish Canadians were less ‘nice’ and more willing to share and open their hearts.”

As we strive to cultivate a community of shalom—of wholeness and flourishing—within our organization, one in which we believe the best in each other, want the best for each other and expect the best from each other, may we be quick to be good neighbours, sharing the gifts of time and vulnerability. May the space between us be holy ground rather than lonely ground.

Lt-Colonel Brian Armstrong is the secretary for personnel.

Photo: © The Canadian Press

Leave a Comment