My parents grew up in different church settings. My dad attended a large, formal Episcopal (Anglican) church in the suburbs while my mother, living on a dirt road in the house my grandfather built, attended a small, country Methodist church. Yet these churches both observed the Christian year. I learned to appreciate that this liturgical calendar is about far more than worship style. In substance, it offers congregations a means of ecumenical fellowship, steady discipleship, meaningful worship and coherent testimony.

The Christian calendar keeps congregations in sync worldwide, pointing to the significance of each day, week, season and year. The seasons that shape the Christian year are Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, Easter and the Season after Pentecost (also known as Ordinary Time). We can tend to confuse and conflate the first three seasons, so this article aims to define and distinguish Advent, Christmas and Epiphany. Future articles will focus on Lent, Easter and the Season after Pentecost. But first, let’s consider how different cultures account for time.

Accounting for Time

Genesis 1 says that God gave the sun, moon and stars as signs for the days, years and seasons. Ancient people observed these objects in the sky and often ascribed significance to cosmic activity. Clusters of stars returned annually to represent characters in an astronomical drama. In some cultures, heavenly bodies represented greater and lesser deities.

Instead of the sky, we now use alarm clocks, “smart” watches, and printed and digital calendars to track time. While some traditions, such as those of Indigenous Peoples, challenge a lifeless view of time, from a purely modernistic viewpoint, days, years and seasons mean nothing more than the productivity, profit or pleasure we can extract from them. Only wishful hearts and wistful minds perceive significance in the lengthening of days after the summer solstice or the rebirth of the moon each lunar month. In this view, the sun, moon and stars, earth and her residents are just soulless material.

But for centuries, Christians across the globe have defied this view. The church insists that time is meaningful. It inherited this attitude from the ancient Jewish backgrounds of first-generation Christians.

Living in Sync: The Christian (Liturgical) Year

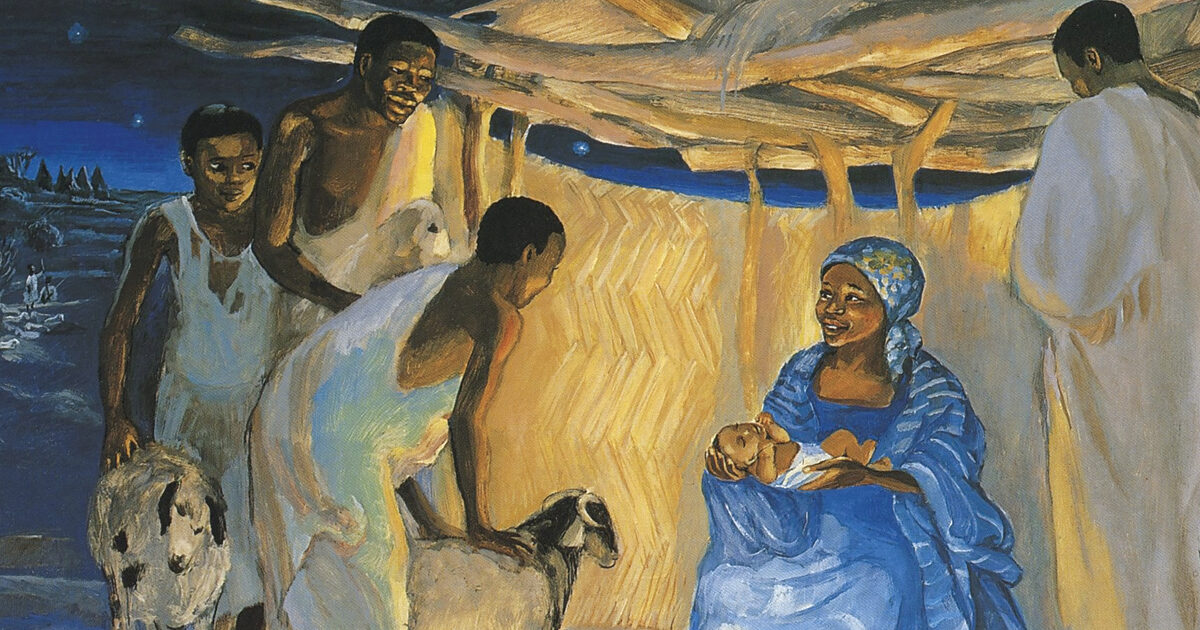

As members of a church that observed the Christian year, my family felt in sync with Scripture readings when visiting other churches and connected to other Christians across time and space. Observing the Christian year, Christians not only hear the gospel but symbolically enact it in their days, weeks and seasons. The Christian year has visual, aural, visceral and tangible dimensions. It is a rich resource for the interrelated tasks of bearIllustration: Vanderbilt Divinity Library. Original source: Librairie de l’Emmanuel ing witness to the gospel (i.e., evangelism), making disciples (see Matthew 28:18-20), and worship. Sadly, many today have lost its rhythms.

To understand the Christian year, we must realize that various holidays (Christmas, Epiphany, Easter, Pentecost, etc.) do not occur arbitrarily, isolated on the calendar. The ancient church set these dates within a coherent narrative. The liturgical calendar invites worshippers to dwell on the significance of an event or a truth. It infuses life with the rhythms and themes of worship. Individual Christians become part of something greater—communal memory, learning and practice. Rather than arbitrary and piecemeal snippets of the gospel message, the Christian calendar presents a sustained witness. Each year, the church tells the gospel story—the history of salvation—and holidays mark significant points in that telling and retelling. Appropriately, it starts with the “Christian New Year”—the season of Advent.

Advent (December 3-24, 2023)

Crowds enthusiastically revel in “New Year” celebrations when the secular calendar turns from December 31 to January 1. But the first Sunday in Advent is the Christian’s New Year’s Day. It is the beginning of an annual drama—telling the story of the triune God and of God’s redemptive intentions in the world.

Advent is a solemn time of anticipation in late autumn. This season begins four Sundays before Christmas and changes dates based on which day of the week Christmas falls on. Advent is longest (28 days) when Christmas falls on a Sunday and shortest (22 days) when it falls on a Monday, as it does in 2023.

As the beginning of the story of God’s redemptive plan, Advent beckons Christians to imagine a time when Jesus and his story were entirely unknown. Scripture readings during Advent focus on Old Testament prophecies of messianic hope and New Testament re-articulations of them. During Advent, the church pretends that the gospel narratives of Jesus’ birth and early life do not exist. The lectionary, which lists Scripture passages to be read on specific dates and occasions, reserves these gospel stories for the seasons of Christmas and Epiphany. During Advent, Christians sit with ancient Israel in solemn anticipation of Messiah’s arrival—Advent means “coming” or “arrival.” It is connected with Christ’s birth by way of anticipation, but not fulfilment.

One familiar tradition is the Advent wreath. On each of the four Sundays before Christmas, the gathered community lights candles in sequence, representing hope, faith, joy and love, adding a flame each week. The third “joy” candle is usually pink or purple to symbolize exuberance. On Christmas Day or on the first Sunday of Christmas, whenever the congregation first assembles during the season of Christmas, they light a special fifth candle—often larger and central to the wreath. This “Christ” candle remains unlit until Christmas to symbolize the sense of unmet yearning for the Messiah.

Christmas (December 25, 2023-January 5, 2024)

Christmas Eve (December 24) is the last day of Advent. Millions of Christians gather each year for a Christmas Eve watchnight service to experience the dramatic shift in mood from solemn Advent to joyful Christmas and to welcome Christmas Day. The anticipation of Advent amplifies the joy of Christmas.

As the beginning of the story of God’s redemptive plan, Advent beckons Christians to imagine a time when Jesus and his story were entirely unknown.

The Christmas season is the 12-day celebration of Jesus’ birth and is the only season that falls on the same dates every year—December 25, the first day of the Christmas season, through January 5, the 12th day of the Christmas season. Hence, the “Twelve Days of Christmas” (see salvationist.ca/articles/the-twelvedays-of-christmas). Lectionary readings during the Christmas season focus on narratives of Jesus’ birth, especially from the Gospel of Luke.

Epiphany (January 6-February 13, 2024)

The Feast of Epiphany (January 6) is the first day of the season that commemorates the appearance of Jesus Christ to the world. Epiphany comes from a Greek word that means “appearing.” Whereas Christmas celebrates his appearing within his close-knit family and his Jewish community, Epiphany celebrates his appearing to the nations.

The visit of the Magi narrated in Matthew 2 was Jesus’ first public appearance to people outside his community, therefore Epiphany highights this event. In some countries, and especially in Latin America, the Feast of Epiphany is bigger than the Feast of Christmas. Some refer to it as Three Kings Day or El Día de los Reyes, and the celebrations and gift-giving are on par with those of Christmas elsewhere. During Epiphany, other Gospel readings include Jesus’ presentation in the temple, his baptism and the transfiguration.

The length of Epiphany depends on the dates of Easter and Lent. Just as the appearance of Jesus Christ to Israel and to the nations was followed by his passion, the celebratory liturgical season of Epiphany is followed by the solemn season of Lent, starting with Ash Wednesday (February 14, 2024).

The Lectionary and the Christian Year

The Revised Common Lectionary used by most churches today is a good guide for observing the seasons of the Christian year. It systematically guides users through significant Old and New Testament readings while focusing on substantial passages from the three Synoptic Gospels, following a three-year cycle—Year A (Matthew), Year B (Mark) and Year C (Luke). 2023-2024 is Year B.

The lectionary allows congregations a balanced diet of messages, challenges preachers to address texts outside their comfort zone and enhances Christian community and discipleship in and beyond the congregation.

You can access the Revised Common Lectionary and a wealth of appropriate resources for worship, including hymns, songs, prayers and artwork, free of charge from the Vanderbilt University Library at lectionary.library.vanderbilt.edu.

The Christian year is a means of ascribing meaning to time, a focus for worship and thanksgiving, an invitation to formation in the likeness of Christ, a tool for teaching and testifying the faith, and a form of resistance to the emptiness ascribed to time by lifeless philosophies.

Dr. Isaiah Allen is assistant professor of religion at Booth University College in Winnipeg.

Illustration: Vanderbilt Divinity Library. Original source: Librairie de l’Emmanuel

This story is from:

Leave a Comment