If it seems like you’re paying more for groceries than you used to, it’s because you are. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation is hitting Canada hard as the price of nearly everything is going up, fast.

According to the most recent data from Statistics Canada, grocery bills are up 3.9 percent year over year, while the cost of gasoline has risen 41.7 percent and shelter 4.8 percent.

This rise in the cost of living is contributing to an increase in food insecurity, with one in eight households in Canada now reporting they do not have access to an adequate diet of healthy food due to financial constraints.

This has led to a surge in demand for Salvation Army programs—and the situation may be about to get worse.

Peter Thomas, community and family services consultant in the corps mission resource department, points to research from the Agri-Food Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University in Halifax, which suggests there is a “perfect economic storm” on the horizon, as inflation meets high unemployment.

“That storm is a big concern for me,” he says. “As The Salvation Army, we need to prepare for it.”

Watching the Numbers

The pandemic has had a marked impact on the need for food support programs across Canada. In March 2021, when Food Banks Canada did its annual Hunger Count, it found that there were more than 1.3 million visits to food banks countrywide in that month alone—an increase of approximately 20 percent compared to 2019.

Numbers are up at The Salvation Army as well. There were 511,000 visits to our food banks between January and October 2021, up from 467,000 visits during the same period in 2020. And the Army served more than 136,000 unique individuals between January and October last year, of whom 47,460 were children and 7,500 seniors.

The overall number of individuals served was even higher in 2020, at the height of the pandemic, when 159,500 individuals were served between January and October. However, after a decrease in 2021, Thomas expects numbers to go up again this year.

“Many of the people coming to our doors have been supported by government programs over the last two years, and now a lot of those programs have stopped,” he says. “That is going to be an incredible factor moving forward.”

Addressing Food Insecurity

Since the pandemic began, the Army has been battling food insecurity on several fronts. As the country headed into lockdown, traditional service delivery models were no longer possible and ministry units had to innovate.

For example, many food banks adopted a “drive-through” approach to food distribution so that clients could do intake assessments over the phone and then pick up their food, without needing to enter a building. Some ministry units provided food delivery for people who could not leave their homes.

“It encouraged me that our ministry units didn’t close; they adapted,” says Thomas.

In line with our vision to be an “innovative partner,” ministry units across the territory benefited from innovation grants, which were distributed by territorial headquarters last August. Of the 44 proposals that received funding, eight were food-related.

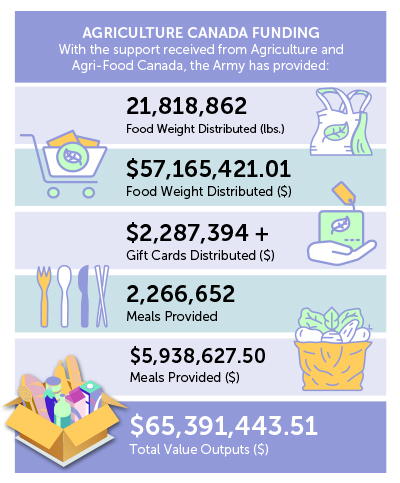

The Army also received substantial support from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada through its Local Food Infrastructure Fund. Since the onset of the pandemic, the Army has received $28.2 million in funding, which has been used by ministry units to provide $65 million in value in terms of food-related services (see box). This funding has supported programs such as “pop-up” food hamper events in Calgary, and the preparation and delivery of nutritious meals to clients of the Army’s Lawson Ministries in Hamilton, Ont., which serves people with developmental disabilities. At the end of 2021, Agriculture Canada announced that further funding would be allocated to the Army—up to $2 million.

The Army also received substantial support from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada through its Local Food Infrastructure Fund. Since the onset of the pandemic, the Army has received $28.2 million in funding, which has been used by ministry units to provide $65 million in value in terms of food-related services (see box). This funding has supported programs such as “pop-up” food hamper events in Calgary, and the preparation and delivery of nutritious meals to clients of the Army’s Lawson Ministries in Hamilton, Ont., which serves people with developmental disabilities. At the end of 2021, Agriculture Canada announced that further funding would be allocated to the Army—up to $2 million.

“The Agriculture Canada funding has been a lifeline—not just for us, but for other organizations, too,” says Thomas.

With these and other programs, including those highlighted here, the Army is committed to tackling food insecurity long-term. But with a “perfect storm” on the horizon, Thomas is inspired by the biblical example of Joseph, who knew a famine was coming to Egypt and prepared storehouses of food.

“Now is the time to get the word out to our community,” he says. “Tough times are coming, and we need your support more than ever so that we can weather the storm.

“And it’s not just money or food, it’s individuals,” he continues. “We need a full army to get behind the shield.”

Support for Migrant Workers

Every year, hundreds of migrant workers come to the Durham Region of Ontario to work at farms and help put food on the tables of Canadians. But many of them cannot put food on their own tables.

This has been especially true since the onset of the pandemic.

“At the beginning of COVID, the workers were asked to stay at the farm, so they were unable to go out for groceries,” explains Elizabe Espinosa, direct/outreach service co-ordinator with Durham Region Migrant Worker Solidarity Program (DRMWSP).

The DRMWSP quickly learned that the workers needed water—the water they had access to was not potable, and unscrupulous vendors were selling them bottled water at inflated prices.

So the DRMWSP put out an appeal to the Whitby, Ont., community for water donations, and that was where The Salvation Army came in. Each month since then, the Army has provided food, water and other essential items to the DRMWSP to distribute to the workers. The average monthly pickup serves more than 200 people.

Though COVID restrictions have eased and the workers are able to leave the farm for shopping, food insecurity is still an issue for them.

Partnering with the DRMWSP was an educational experience for Major Donette Percy, corps officer, Whitby Community Church. “I never knew all the details of how much they were provided for while working on the farms,” she says. “We realized, if this is the amount they pay for board and this is the amount they’re sending home—well, what do they have left?”

The migrant workers also face issues around the kinds of food they have access to. “Most of them are located in rural areas, far away from large supermarkets,” notes Espinosa. “So when it comes to cultural-based foods, they are not able to gather what they really eat.”

With workers hailing from countries such as Mexico, Guatemala, Barbados, Jamaica and Thailand, the DRMWSP gives the Army a list of cultural items that the workers would usually consume. The Army then sets aside donations as they come in to try to fulfil that list.

“Our partnership with The Salvation Army is the best thing that could have happened to us because no matter how much funding you have, there is never enough,” says Espinosa. “Even in the tough months when we don’t have much, The Salvation Army is like our angel. Without them, we could not give so much support to the workers.”

“These workers are part of our community,” says Major Percy. “If we can help provide for them and put a smile on their faces, we’re glad to do it.”

A Fresh Free Market

As corps officer in the rural town of Maple Creek, Sask., Major Ed Dean is in a unique position when it comes to food donations.

“I can make five phone calls and get 2,000 pounds of potatoes,” he smiles. “Our community is very generous.”

The corps regularly receives large food donations from its local partners, which are first distributed through the Army’s food bank. But with literal tons of food being donated, there is always more than enough to go around. As the corps considered what to do with the surplus, they were also looking for new ways to address food insecurity in the area.

“We wanted to reach people who wouldn’t access the food bank or didn’t qualify for the food bank,” says Major Dean.

That rethinking process led Major Dean to come up with the idea of the Free Market. Now running for almost three years, the Free Market is held at the corps three or four times a week.

The first market was held after the Army received a one-ton donation of potatoes. “We called it The Great Potato Giveaway,” Major Dean says. “And it was just that: we told the community, come and take what you would like.”

The items featured at the Free Market are different each time, depending on what donations come in. A recent market, for example, included bread, lentils, peanut butter, cereal, carrots, eggs, yogurt and juice.

But no matter what’s on offer, the philosophy remains the same.

“There is no limit on how much you can have at the Free Market,” Major Dean explains, “though we have signs up that say, please take what you will use. And there’s no questions as to who you are.”

While no names are taken, the corps does keep track of numbers: the Free Market serves more than 200 people each week and distributes an average of 4,000 pounds of food each month. The corps also serves 40 families each month through the food bank, provides 60 meals to seniors each Wednesday, and provides school meals twice a week.

In a town of just 2,000 people, that’s a significant service—and it’s done without much outside financial support such as large corporate donations, as is often the case in larger centres.

“Most of the donations that come in are from Hutterite colonies,” Major Dean notes. “Their philosophy is, they would rather see it used than wasted, and we are the benefactors. So I’m never out of potatoes in my food bank.”

Salmon Arm’s Food Forest

Every time Lieutenant Joel Torrens was outside working on his corps’ new community food forest last year, he’d always get the same question from people walking by.

“They’d say, ‘Aren’t you worried about people stealing?’ And I’d say, ‘That’s not possible,’ ” he smiles. “They’re supposed to take it. We want them to!”

Unlike a community garden, which is typically done in raised planters, The Salvation Army’s food forest in Salmon Arm, B.C., is an edible landscape designed to mimic a forest. “Everything serves a purpose,” Lieutenant Torrens, corps officer at New Hope Community Church, explains. “If it’s not edible, then it contributes to pollination or pest control. It all works together.”

Working with community partners such as the Shuswap Food Action Society, the food forest was designed by permaculturalist Keli Westgate and is planted on the grounds of the corps’ community and family services building. For Lieutenant Torrens, the community forest is a much better use of the space. “It has become a part of our mission and not just a lawn we have to maintain.”

The food forest will yield a variety of produce, from sunflowers and squash to beans, cucumbers, plums and more. Best of all, the forest is free and open to anyone at any time.

“People aren’t hungry on a schedule,” notes Lieutenant Torrens. “Food banks have hours of operation, but if someone’s hungry at 8 p.m., they’re going to be able to walk by here and find something to eat.”

In terms of the food insecurity challenges he sees in Salmon Arm, Lieutenant Torrens points out that “not everyone who’s accessing a food bank has the facilities to store or cook food.” Ready-to-eat produce is one way the corps can serve people who are living vulnerably, for example, in hotel rooms or tents.

While the forest is low maintenance, work will be required to keep it going—for example, pruning, watering and harvesting. That’s where Lieutenant Torrens hopes the forest won’t be just for growing food, but also bringing people together.

“This is for the community and that means it has to be by the community,” he says. “We need people to get involved and get excited about it and so far they have, so we are confident going forward with this.”

Along with established gardeners, he hopes to draw in groups such as students and seniors who may not be able to maintain a garden on their own anymore.

“We’ve called it the Lighthouse Community Food Forest because we want it to be a beacon of hope,” says Lieutenant Torrens. “It’s a great way for us to live the mission of The Salvation Army in this community.”

The food forest expects to celebrate its first harvest later this year.

This story is from:

Leave a Comment