Sometimes Christians in North America say, “We're persecuted!” While Christianity has faced increasing cultural disdain in recent years, to call this treatment persecution “stretches the definition violently,” says one writer in Relevant magazine.

The first three centuries of the church are known as “the age of martyrs.” The Roman Empire mercilessly persecuted the early Christians, who refused to worship the emperor as divine or make sacrifices to Roman gods. They were tortured, thrown to wild animals, set on fire and used as human torches. Their willing sacrifices led to the rapid growth and spread of Christianity. The church father Tertullian wrote, “The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.”

Today, there are still places in the world where Christians are jailed and killed for their faith, where they must meet in secret. Sarnia, Ont., where I live, isn't one of them. I can go to church openly, listen to Christian radio while driving home and then watch a Christian TV show or movie. We have Christian daycares, schools and universities; Christian magazines, books and publishing companies; Christian games, greeting cards and dating websites.

It's true that Christians are sometimes ridiculed and marginalized, but being made fun of is not persecution. Being a Christian will not get me killed. So why does a certain segment of Christianity in North America claim persecution? I think it's because we're losing our grip on power, and we're afraid.

In the fourth century, the emperor Constantine adopted Christianity after a key battle and made it legal. It became the official religion of the empire and the church gained tremendous power, influence and cultural dominance. This was the beginning of Christendom, a partnership between church and state that shaped Western society.

Christians are used to being the dominant majority in our culture, but that's changing. We now live in a pluralistic society, made up of many traditions, cultures and religions. Not everyone thinks or believes the way we do. But acknowledging and respecting our differences doesn't mean we have compromised our faith. It means we understand that religious freedom means freedom for everybody.

Scripture is clear that living as a Christian will bring opposition: “Blessed are you when people insult you, persecute you and falsely say all kinds of evil against you because of me. Rejoice and be glad, because great is your reward in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you” (Matthew 5:11-12); “In fact, everyone who wants to live a godly life in Christ Jesus will be persecuted” (2 Timothy 3:12).

In my opinion, we aren't persecuted, but we do have a persecution, or martyr, complex—an unfounded and obsessive fear or sense that we are the object of collective mistreatment or hostility.

Do we read persecution into things because we want to prove our worthiness? Has it become a badge of honour that inflates our pride? Something that marks us as part of an elite group? Alan Noble, an English professor at Oklahoma Baptist University, writes about the dangers of a misguided understanding of persecution in The Atlantic: “The danger of this view is that believers can come to see victimhood as an essential part of their identity … the real problem with many persecution narratives in Christian culture: they fetishize suffering.”

It's true that the church no longer occupies a central place in our culture—but is that a bad thing? When the church became a powerful, state institution, abuse and corruption followed. Throughout history, reform movements have arisen to call the church back to its roots—to be countercultural, pointing to a different way of living, different values.

Bishop Michael Curry, presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States, writes: “I think the detachment of the Christian religion from the culture in which we are living—the end of the age of Christendom—is an opportunity … [the] church can now emerge, [unencumbered] by the institutional arrangements that were part of the age of Christendom, and that's an opportunity for some real religion. Now we [can] get on with the work of really following Jesus, really being his disciples and the community of his disciples in the world.”

We aren't persecuted just because we're no longer on top. Let's get back to being the church—salt and light in a dark world.

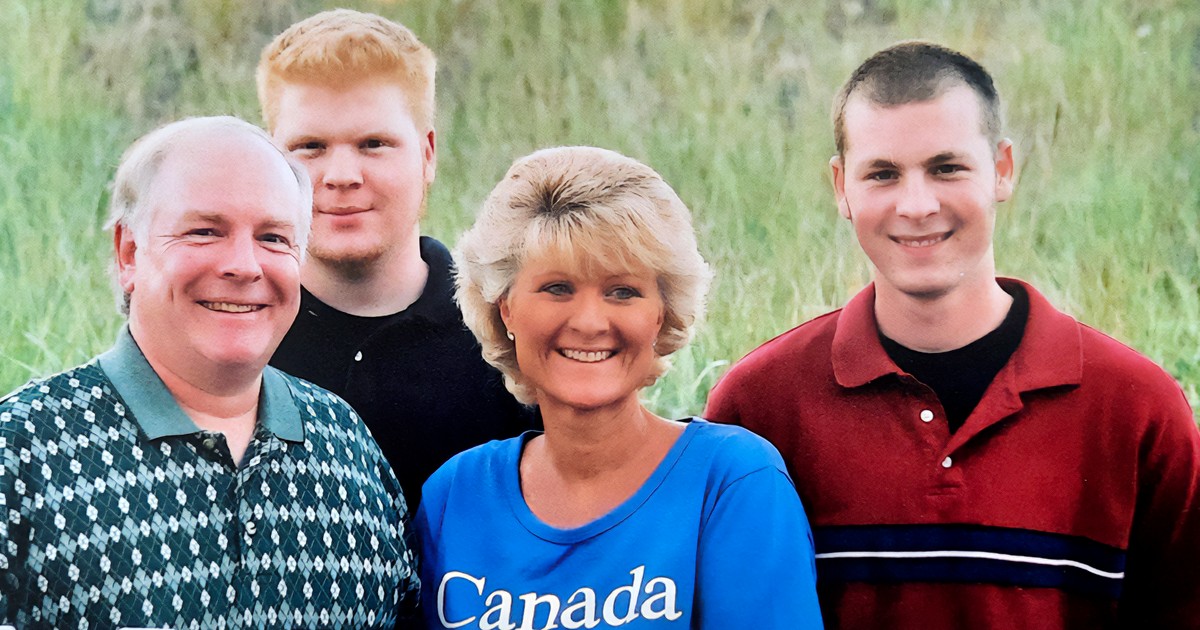

Captain Mark Braye is the corps officer at Sarnia Community Church, Ont.

Since this article was written, belief in Christian persecution has evolved into paranoia. It has gotten to the point in the USA where President Trump has appointed authorities to as he says “irradicate”, such persecution. This will probably result in violence. It also looks a first step to a theocratic government. Let’ s not import the paranoia south of the border,