I first encountered Scott Erickson’s work in December 2022. It was a memorable season in my life: my wife, Julia, was expecting our first child, Elias. Christmas that year felt different. The word “incarnation” had always carried weight for me as a pastor, but during those months it became real in ways I had never experienced before. Watching Julia carry life, preparing for sleepless nights and imagining what it would mean to hold our son for the first time pulled me deeper into the mystery of God becoming flesh.

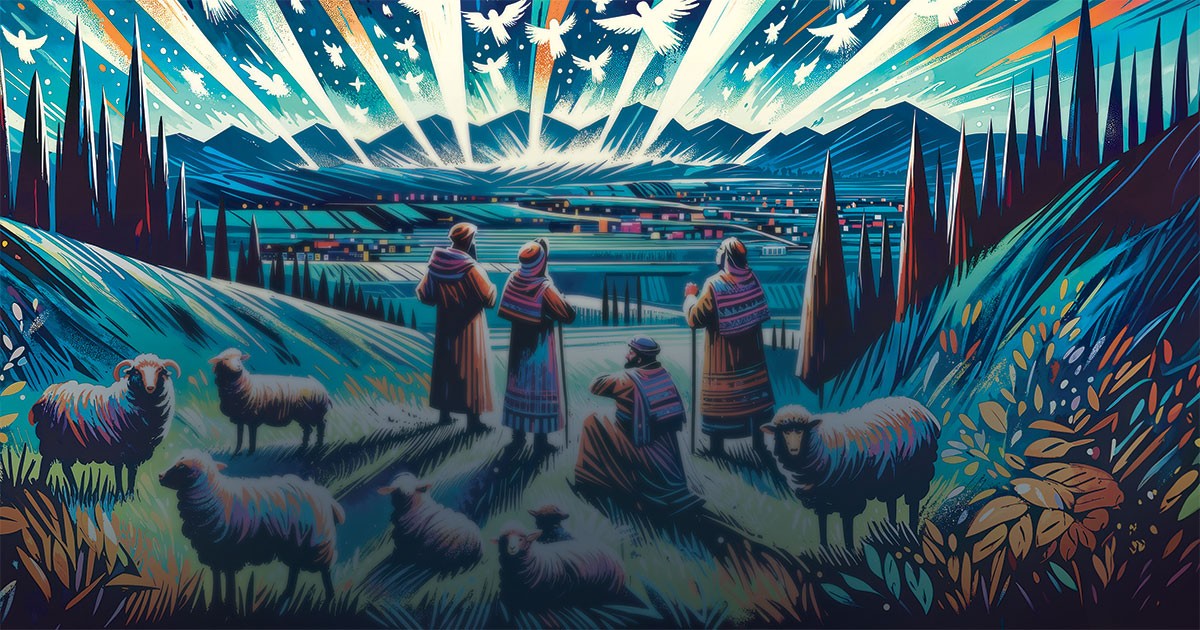

That was when I came across Erickson’s art on Instagram (@scottthepainter). His Advent series struck me with its honesty. The images were not polished greeting-card versions of the Christmas story. They were raw and simple. They acknowledged the messiness of birth, the fear of uncertainty and the vulnerability of God choosing to dwell among us in human form. I remember stopping my scrolling, staring at one of his pieces and realizing: This is what I’m trying to put into words in my preaching, but here it is in a single image.

When the opportunity came two years later to host Erickson’s Advent art show at our corps in Lethbridge, Alta., I knew it was something we needed to do. We set it up as a drop-in event throughout the month of December. The idea was simple: in a season when calendars are full and noise is constant, we would provide a quiet space to walk slowly, view the art, read the reflections and consider again what it means for Christ to come into our world.

Waiting and Trust

The decision to host the show was not just about novelty. Art has always played an essential role in the life of the church. Long before most believers could read, the stained-glass windows, sculptures and paintings of cathedrals told the story of salvation. Erickson’s art does this especially well. It asks questions more than it provides answers, opening space for the Spirit to speak.

Advent, at its heart, is about waiting in the dark for light to come. It is about holding together hope and longing, joy and sorrow. The Salvation Army’s fourth doctrine tells us that in the Incarnation, Jesus entered our world as fully God and fully man. But art helps us feel that truth. When I looked at Erickson’s image of Mary, with vulnerability written on her face, I could not escape the reality that the Son of God chose to be carried in such fragile circumstances. When I saw his images of waiting and uncertainty, I was reminded that faith often begins not with certainty but with trust in the middle of questions.

Weakness and Vulnerability

art show of work by Scott Erickson, with accompanying meditations from his book Honest Advent

For our congregation, the Advent art show was deeply spiritual. People entered quietly, some alone, some with their children, and moved from piece to piece. Each poster included a QR code linking to Erickson’s meditations, so people could listen or read reflections as they went. What struck me was how long people stayed. In a season when so much is rushed, here was an experience that invited lingering.

The feedback was remarkable. Longtime Christians told me that the images helped them see the story they thought they knew with fresh eyes. One person said they had never considered how terrifying it would have been for Mary to say yes to God, and how that yes was not just a matter of faith but of real risk. Another told me that the image of Christ’s vulnerability as an infant broke through their cynicism about Christmas and reminded them that God meets us in weakness.

We also had people from the wider community, some with no church background, stop in and engage. They found in the art an entry point that did not require theological training. For them, the Incarnation became approachable: not a distant doctrine, but a story of God who chooses to come close.

God With Us

What stayed with me most was how the show revealed the tension at the heart of Advent. The Apostle Paul writes that Christ, “Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness” (Philippians 2:6-7). We sometimes recite those words so quickly that they lose their shock. But Erickson’s art pressed me to pause. God does not save the world by power from afar but by entering the very stuff of human life: hunger, fatigue, birth pains and family struggle.

In hosting this show, I realized how much we need that reminder. The church has always proclaimed that God is with us, yet at Christmas it is easy to sanitize the story until it becomes safe and predictable. But the Incarnation was not safe. It was as real as a young woman’s fear, as uncertain as a refugee family fleeing violence, as vulnerable as a newborn in a manger.

And that is good news. Because it means that God meets us in the raw places of our own lives. The message of Advent is not that we must escape the world’s mess to find God, but that God has entered our mess to redeem it from within.

Lieutenant Zach Marshall is the corps officer and community services officer at Community Church of Lethbridge, Alta.

Illustrations: Scott Erickson

For more information about Scott Erickson’s art and resources for the church, visit https://scottericksonartshop.com/collections/downloadable-art-shows.

What a creative way to encourage spiritual intimacy: visual art that brings viewers close to a fragile God. Sometimes the good news needs no words!