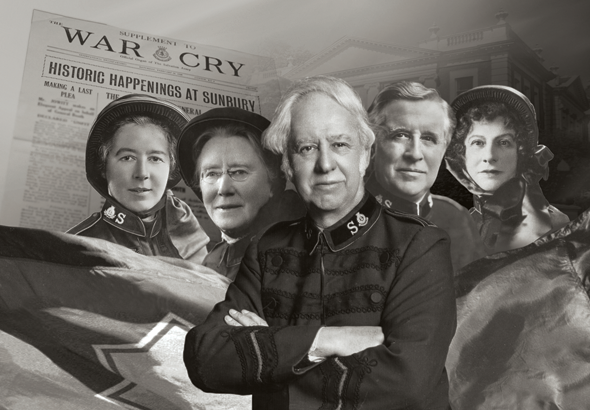

It was gone midnight when in the early hours of Thursday, January 16, 1929, the president of the first High Council, Commissioner James Hay, informed the 63 members gathered in the council chamber at Sunbury Court, near London, England, that by their vote just concluded, Bramwell Booth was no longer the General of The Salvation Army.

It was gone midnight when in the early hours of Thursday, January 16, 1929, the president of the first High Council, Commissioner James Hay, informed the 63 members gathered in the council chamber at Sunbury Court, near London, England, that by their vote just concluded, Bramwell Booth was no longer the General of The Salvation Army.

The atmosphere was sombre. “The silence of the death chamber was there,” recalls Commissioner Samuel Brengle. The ballot was the culmination of what had been a long-drawn and traumatic saga. The High Council itself had been in session for five weeks, but the drama had been unfolding for a year or more. It was with choked voices that the members sang: “When we cannot see our way, let us trust and still obey.”

The next day the High Council met to elect a successor to General Bramwell Booth. Nomination papers were distributed for members to return unsigned. That the Chief of the Staff, Commissioner Edward Higgins, and Commander Evangeline Booth would be nominated was a foregone conclusion. But there were three further nominations: Commissioner Catherine Booth, daughter of Bramwell and Florence Booth; Commissioner James Hay; and Lt-Commissioner Charles Rich, territorial commander of the Canada West Territory. The last three all declined to be nominated, leaving Evangeline Booth and Edward Higgins as the two candidates.

But there was no election that day. The story of the 1929 crisis, characterised by many twists and turns, was yet again to head in an unexpected direction. The election of the next General did not take place until four weeks later, when Edward Higgins was chosen.

How could it be that such a remarkable and revered figure as Bramwell Booth was removed from office by the High Council? The crux of the crisis was whether Generals should continue to have the right to nominate their successors by placing the name in a sealed envelope—as William Booth had decreed—or be elected. Bramwell Booth felt it his duty to resist such reform.

The reform movement had sprung to life on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, and had become particularly strong in the United States where Commander Evangeline Booth was its leading voice. In Canada, the pressure for reform was more muted, though Evangeline Booth noted with approval in April 1928 that an appeal for constitutional reform addressed by senior Canadian officers to Bramwell Booth “made a tremendous impression, not only upon the General, but upon all leading commissioners.”

Lt-Commissioner Gunpei Yamamuro of Japan records in his diary that he opted to travel to the High Council via Canada rather than the United States so that he would not be over-influenced by reform thinking, and sailed for London, England, in the company of Lt-Commissioner Charles Rich and Lt-Commissioner William Maxwell (territorial commander, Canada East). In the end, all three were to vote for Bramwell Booth's deposition.

With its large cast of well-known Army historical figures, its human drama and its span from 1875 to the present, the story of the 1929 crisis is a remarkable aspect of Salvation Army history by any measure. If it has taken 80 years for the story to be told in full by a Salvationist writer it is because very real sensitivities are involved—sensitivities that even now have to be carefully weighed.

There is no doubt, however, that what stunned the Army in 1929 shaped its future and set it on a path of reform that continues to this day. The crisis of 1929 is therefore part of the heritage of every Salvationist.

1929 by John Larsson is published by Inter-national Headquarters (Salvation Books). Order online at SalvationArmy.ca/store.

1929 by John Larsson is published by Inter-national Headquarters (Salvation Books). Order online at SalvationArmy.ca/store.

While Bramwell Booth was physically unable to perform the duties of his generalship during his final few months, that is not why the High Council voted to depose him. They did so because they disagreed with Bramwell's assertion that as general he could pick his own successor. Wanting to free the Army from the rule of a powerful family they deposed Bramwell - a move that likely hastened his death.

It begs the question whether nepotism still exists in the Army. Why is it that every general (with the exception of the Founder himself) was an officer's kid? Why do they ask you to list all your relatives who are officers on training college application forms, even today? I hope it is because they want to avoid new officers being supervised by their officer relations. I hope it's not meant to determine a candidates 'pedigree'. Anyway, a great book and a great story from our history that we can learn from today.