The Early Church was faced with the false doctrine of Gnosticism. The doctrine taught the separation of spirit and matter: that the spirit was sacred and matter was secular. This false doctrine finds its roots in the dualistic philosophy that the Greek philosopher Plato introduced to Western thought.

The Early Church was faced with the false doctrine of Gnosticism. The doctrine taught the separation of spirit and matter: that the spirit was sacred and matter was secular. This false doctrine finds its roots in the dualistic philosophy that the Greek philosopher Plato introduced to Western thought.

While Gnosticism is no longer a threat to Christianity, the underlying philosophy of dualism is alive and well. Many of us have separated our lives into two distinct realms: the sacred and the secular. In the secular realm, we work, pay our bills, go to school and participate in popular culture to some extent. In the sacred, we pray, talk to God and find spiritual meaning. The more we remove ourselves from the distractions or pollution of the secular, the more “spiritual” we believe we are.

Most of us experience an extreme tension between the two realms. We live in the secular world during the majority of our day, feeling a little guilty that we are so “worldly.” Others have developed an intense fear and distrust of anything secular, and long to be free from the world.

Christian Subculture

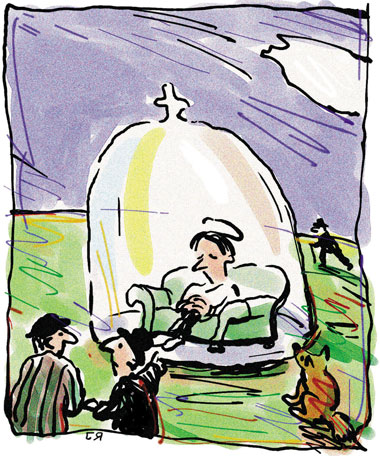

What is the solution to this tension? For many, it has been to expand the sacred world by creating a subculture that has all the same features as the secular world but has a Christian stamp of approval. We construct our own clubs where everyone believes the same thing, listens to the same music and knows the secret handshake. What safety! Everything within our club is neatly defined and we all know where everyone else stands, based on their ability to keep the club rules.

We stamp “Christian” and “non-Christian” on music, movies, education, careers and friends. We retreat into our subculture and limit our contact with the secular culture as much as possible. We create extra-biblical rules that, like a teacher's checklist, help us quickly critique an individual's “Godliness.” We think we will be safe in our newly created sacred world.

We often move in separate realms than the people we are called to love and reach … I know many Christians who can't think of one friend that is an unbeliever

Of course there is not a uniform Christian subculture. For one group, the criterion for sacred music is hymn style; for another, Christian rock might be OK. In most cases the rules are defined by church (or denomination) leadership who apparently have special knowledge about what is “pleasing” to God. Few members of the subculture ever examine or question its existence. Few look at its place in relationship to the Gospel.

What specifically is sacred and secular is not the problem; rather, it is the fact that the distinction exists at all.

Christian Subculture and the Gospel

Jesus came to set captives free and to proclaim the favour of God. If we are to be about that same mission we must be willing to examine the current Christian subculture in light of the gospel mission. The following are observations on how the Christian subculture can negatively affect our ability to carry out this mission:

1. We lose our ability to relate to unbelievers. As we retreat into the Christian subculture we lose the ability to speak the same language and to understand the context in which the Gospel needs to be presented. Secular culture is nothing more than the values, beliefs, hopes and dreams of the people we are trying to reach. When we totally remove ourselves from it, we miss out on the greatest tool that we have to understand those who need Christ.

2. The communication of the Gospel is hindered. The Christian subculture has its own “Christianized” language and it becomes very difficult to communicate effectively with those outside that subculture. Effective communication is based on understanding the context and the symbols associated with the culture. If we have nothing in common, don't understand their world, and can't speak their language, how can we hope to reach them?

3. We limit our contact with those we are called to love and reach. Any good relationship, which is the foundation of evangelism, must begin with personal contact. By removing ourselves from the secular world we minimize this contact. I know many Christians who can't think of one friend that is an unbeliever.

4. Christians never learn how to think about Christianity in the “real world.” I had friends in college who once exposed to the “real world” of secular education began to question what they had always believed. Their Christian subculture had no room for tension, doubt or free thought and subsequently their faith crumbled under pressure. Isolation might protect us in the short-term, but we will reap the long-term consequences.

5. Christian subculture helps support a Pharisaic culture of rules designed to keep people conformed to the “image” of Christianity. The more we congregate in the subculture, the stronger the “rules” of the subculture (legitimate or not), e.g. drinking, smoking and tattoos are clearly wrong, but why? Does anybody know? And why do we care so much? All this congregating in the subculture alone puts our eyes on one another, rather than the world that so desperately needs to be reached.

Jesus' Response

The religious subculture of Jesus' time is very similar to what we see today. The Pharisees mastered external holiness and had well defined rules of what it meant to be “godly.” Their very name means “separated ones.” Jesus makes it clear that they missed the point. God didn't want them to retreat into a separate subculture. He wanted their heart; he wanted to use them as his instruments of love to his people.

Jesus had no illusion of a sacred and secular world. He lived in the “world” without conforming to it. His use of parables illustrates his command of the local culture and his ability to use that understanding to speak truth.

What Now?

Popular culture and the Christian are strange bedfellows. God does not desire us to create and hide inside a separate world or culture. At the same time, God does not want us to become simply another consumer of popular culture, allowing it to shape our lives.

I believe that the worldview that creates a separation between secular and sacred is not God's intent. Retreating from the world into a Christian subculture creates a small and weak God, ties up his people with legalism and hinders the Good News from being lived out where it is needed the most.

The Christian who desires to live “Godly in Christ Jesus” is left in a place of extreme tension between running away from and running to popular culture. This tension is hard to resolve and so we often fall into separatism or syncretism, we run from or run headlong into the embrace of popular culture.

God does not try to remove the tension. Instead, he calls us to live in the midst of the tension. Pop culture is not to be simply enjoyed by the believer, consumed unfiltered; rather, the believer can and should use culture to hear God's voice and understand the lost.

Sanctification of Culture: “Hear God”

Few Christians would argue that God speaks powerfully through nature. If God can speak through nature, why not through a beautiful poem, a haunting film or a well-crafted lyric? Western Christianity has emphasized God's transcendent nature, His “wholly otherness” at the expense of his imminence, his intimate presence in everyday activities. The recent interest in Celtic Christianity within the church indicates this is changing. Celtic Christians “saw” God in every area of their daily lives. From lighting the morning fire to working the fields, each became an opportunity to commune with their Maker.

Between demonizing and embracing popular culture, there lies an opportunity for God to sanctify culture. The term sanctification comes from the Old Testament temple. Common items, like bowls and cups were sanctified―set apart for holy use in the temple. These common things, created for very mundane purposes, were taken and used by God for his plans and purposes.

While the temple and its vessels have disappeared, I have little doubt that God still desires to speak to us through common everyday things. Instead of limiting God's activities in our life to a single day of the week or a short, morning devotion, why not find him on the radio, or in the newspaper or at the art gallery?

Interpretation of Culture: “Know the Lost”

Imagine visiting an isolated tribe in the Amazon jungle and sharing the Gospel with them in English, a language they cannot understand, while using examples of the Internet, something they have never heard of. Would you be surprised if they didn't respond to the message? Complete foolishness! The Gospel must be communicated in the context of the people we are trying to reach.

Popular culture is an expression of the value systems, beliefs, hopes, fears and worldview of the people who create it. While it does not replace real loving relationships with people, culture serves as a guidebook by which missionaries can begin to understand the issues that are important to the people they seek to reach and how the Gospel applies. They must learn the language, the customs and, through this process, gain insight in how to reach a particular people group.

If missionaries in the developing world are students of culture, why aren't North American Christians? Instead of being students, we are secret society members. We have our own language, our own festivals and our own arts. In some cases, our only friends are Christians, leaving us to guess at what the unsaved believe, think, desire and hope for.

Paul knew how to use popular culture for Christ. In Acts 17, Paul visits Athens, walking among the pagan temples. He is “looking carefully” at the pagan gods. Paul was not worshiping at the pagan temple, but studying the local culture. He used his understanding of the culture as a handhold by which he could share the Gospel to the people of Athens in a way that was relevant to their experience.

Brave New World

A right understanding of popular culture leaves the believer in an uncharted new place, a place of great danger and potential. Danger is conforming or separating; potential is hearing and knowing. It is a place that requires total reliance on God to bring us through safely and use us effectively. It won't be easy, but since when is the way of the cross easy?

Leave a Comment