I have been thinking a lot about the relationship between ministry and success. Does God call us to ministry that will be successful? I see many involved in ministry who work under the assumption that the call of God is a call to be successful in that ministry. I know that when I entered into my work as a professor I hoped for success—however one might measure that. Now as I bear more administrative responsibilities, I hope that my investment of time and energy will be successful. As I talk with officers who are moving into new appointments, over and over again I hear about their hopes and dreams for their time in those appointments. There is nothing wrong with this. In fact, I would wish that anyone undertaking new responsibilities would engage them with enthusiasm, vision and hope. Furthermore, I would want them to engage that new ministry with a determination to be as successful as possible.

I have been thinking a lot about the relationship between ministry and success. Does God call us to ministry that will be successful? I see many involved in ministry who work under the assumption that the call of God is a call to be successful in that ministry. I know that when I entered into my work as a professor I hoped for success—however one might measure that. Now as I bear more administrative responsibilities, I hope that my investment of time and energy will be successful. As I talk with officers who are moving into new appointments, over and over again I hear about their hopes and dreams for their time in those appointments. There is nothing wrong with this. In fact, I would wish that anyone undertaking new responsibilities would engage them with enthusiasm, vision and hope. Furthermore, I would want them to engage that new ministry with a determination to be as successful as possible.

Of course, we could discuss what such success in ministry and service would look like and what results it would bring. What does it mean to be successful in ministry and service? Is it really reflected in statistics, or the number of people served, or in growing attendance at our corps? Does personal success mean that we live comfortably ensconced in a middle-class lifestyle? Does it mean that we receive public honours and recognition of our efforts? Does it mean that we will quickly move on to another—and better—ministry with a higher profile and more responsibility?

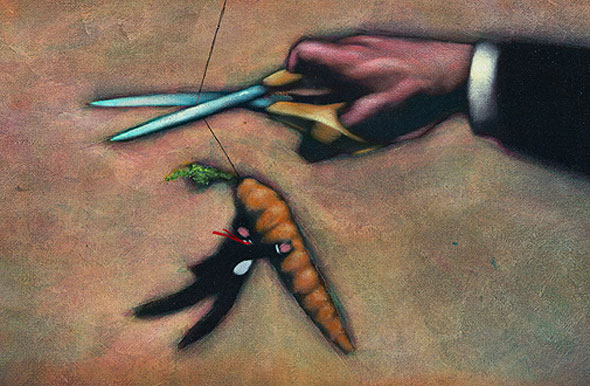

These images of success are complicated for me by one thing. In studying the Scriptures, I don't see many of the great heroes of the Bible as successful in their day—at least in terms that we usually associate with success. At the end of their lives, the outcome of their life's work appears to have been ambiguous at best. Let me illustrate what I mean.

I begin with the prophet Amos. He lived in the eighth century before Christ. What we can discern from the book of Amos is that he was settled in his life as a shepherd and a dresser of sycamore trees. But then he received a compelling call from God to go and prophesy to the people of Israel. He left his homeland, Judah, and travelled north to Israel. There he spoke a prophetic word that criticized Israel and its leadership for rampant social injustice. Amos railed against worship that was not matched with a commitment to the poor. His criticism turned to condemnation as Amos sharply announced the end of Israel, to be brought about by God, as a consequence of this social injustice. So harsh was Amos' critique that it drew the attention of the king of Israel and his priest at Bethel. Amos was then expelled from Israel.

The question that arises is this: Was Amos successful in his prophetic ministry? If we were to judge his success by the effects that could be seen in his own time, the answer clearly would be no. Amos did not avert the looming disaster of Israel's destruction. His critique of social injustice had little impact; there is no evidence that it resulted in the improvement of life for even one of the poor of his day. He was deported as a threat to national security and ended his days in anonymity. By most of the standards of success that we would apply, we would have to judge that the prophetic ministry of Amos was a dismal failure.

I don't see many of the great heroes of the Bible as successful in their day—at least in terms that we usually associate with success

If we turn to Isaiah, we find that his call to the prophetic vocation was a call to frustration and failure. When his commission was given to him, Isaiah found that he was called to harden the hearts of the people of Judah and to prevent them from turning back to God (Isaiah 6:9-10). Isaiah was called to turn people away from God! So disconcerting was this vocation that Isaiah called out in protest: “For how long, O Lord?” (v. 11). God's response to Isaiah's objection was even less comforting. He was to carry out this mission until the cities lay waste and the land was destroyed. It would take an extraordinary human being to embrace a call that from the outset was to be marked by frustration and failure—at least failure by most standards. Nonetheless, during his prophetic career, Isaiah proclaimed the word of the Lord to kings and officials. He kept (often uncomfortable) company with several kings—challenging, cajoling and condemning them. Tradition (which we cannot confirm) tells us that his life ended in a gruesome manner at the hands of King Manasseh—arguably the worst king Judah ever had.

Was Isaiah successful? For the most part, it wouldn't seem so. He was in constant conflict with those around him. He failed to change the policy of King Ahaz who sought Assyrian help in the face of the threat of invasion instead of trusting in God. The reforms of King Hezekiah, supported by Isaiah, were not long-lasting―they quickly evaporated after Hezekiah's death. According to tradition, as Isaiah's life ended, Judah was entering into one of the darkest periods in its history. His success certainly would not have been apparent to those around him!

Jeremiah was called to be a prophet in a time of great crisis in the kingdom of Judah. The tiny country was caught in a tug-of-war between the superpowers of the day. This precarious situation was complicated by the religious and moral corruption that had crippled Judah's leadership. The prophet was called upon to be a clarion voice in a desperate time. As it turned out, Jeremiah experienced little more than alienation from his own people as a result. His summons to repentance and change garnered little positive response. Instead, his warning drew hostility and assassination plots. But more devastating than the alienation from his own people was the alienation from God that Jeremiah felt. In his so-called “confessions” that are scattered throughout chapters 11-20 we find the prophet baring his soul to God in language that is at least confrontational, and on some occasions blasphemous.

Was Jeremiah's prophetic ministry successful? It would appear not. For his prophetic pronouncements did not save Judah from destruction, and there is little indication that his efforts resulted in a conversion of character in more than a handful of his listeners. Jeremiah was accused of treason and taken against his will to Egypt where he died in exile.

Turning to the New Testament, we could consider the Apostle Paul. Surely, we might suggest, his ministry was a success. But let's look more closely at the results of Paul's ministry.

Paul did establish a number of churches throughout the ancient world. But those churches were almost invariably rocked by conflict and heresy. The Corinthian church was a fractious community that quickly lost its loyalty to Paul and broke into a number of factions, giving their allegiance to other, more charismatic leaders. The Galatians quickly abandoned the Gospel that Paul had preached and rejected Paul's ministry. The Thessalonian church misunderstood Paul's message and he had to write to them urgently to set them straight. Paul was dogged by detractors who questioned his motives, his Gospel and his vocation.

The outcome of this brief survey of major biblical figures who were called into God's service (and others could be added) is to raise a question about whether when God calls people to ministry and service he calls them to success that can be measured. I would suggest, on the basis of the biblical materials we have considered, that God does not, first of all, call us to success as we would understand it. We have no guarantees that faithfulness to our vocation will lead to measurable and public success. But if God does not call us to success, to what are we called?

As I read the prophets and the letters of Paul, one overwhelming conviction becomes apparent. God called them not to success, but rather to obedience and faithfulness. There is a striking difference between the two. Amos was not called to go to Israel to turn Israel around, but rather to be obedient and faithful to God by speaking God's word to the rebellious kingdom of Israel. If Israel had turned back to God, all the better. But success in that way was not the bedrock of Amos' prophetic ministry. Isaiah was not called upon to produce repentance in the hearts of the people of Judah, but rather to speak faithfully the word of the Lord. Jeremiah was not called upon to avert the destruction of Judah and Jerusalem by the Babylonians, but rather to be obedient to his call to be a “bronze wall” in the midst of Judah. The Apostle Paul was not called upon to establish perfect churches, but rather to fulfil his mission as the “apostle to the Gentiles.”

My point is really very simple: when God calls us to service and ministry in his name, success is not the primary goal. Rather, faithfulness and obedience to God and the vocation God has given us are the goals we should pursue. We should recognize, as the prophets and Paul were forced to realize, that success may be judged by God using a significantly different standard from one we would naturally choose.

This is not an excuse to wallow in ineffectiveness and to settle for less than our best in the service of God. It certainly is not a call to abandon the effort to make ourselves better at what we have been called to do and be. It is, rather, a call to recognize that in the end the success of the investment of our lives is, for the most part, beyond our control. What we are called upon to do is to fulfil faithfully the vocation God has given us and to obey that divine call. The rest may be left with confidence, in the hands of God.

Dr. Donald E. Burke is President of The Salvation Army's Booth College in Winnipeg.

My experience is that at times this leads me to be profoundly "conservative" in the sense that I search for those things/ideas/values/truths to which I should be uncompromisingly committed and, at the same time, more "liberal" in the sense that I am prepared to rework/challenge/discard/reform those things/ideas/values/truths which are more maleable. The discernment of the distinction between these two often is fraught with uncertainty. But I also believe that God uses even our most paltry and ineffective efforts to great effect. Perhaps I'm revealing one of the characteristics of the way I think and the way in which I read the Bible---generally, I think dialectically, juxtaposing two apparently contradictory thoughts in a creative tension, refusing to think that only one can express what is true.

Thanks again for your comments. I have enjoyed reading them.