Ricardo and Lisa Walters are Salvationists based in Cape Town, South Africa. Ricardo leads IHQ's all-Africa regional facilitation team, which focuses on HIV/AIDS, health and community development through integrated mission. Lisa, a Canadian expatriate, has worked with the Army in Africa for 10 years—in South Africa with the divisional HIV/AIDS team, at a divisional training school, at Care Haven (a shelter for battered women and children) and, since 2005, with the all-Africa regional facilitation team. Geoff Moulton, assistant editor-in-chief, interviewed Ricardo and Lisa about their work in Africa.

Ricardo and Lisa Walters are Salvationists based in Cape Town, South Africa. Ricardo leads IHQ's all-Africa regional facilitation team, which focuses on HIV/AIDS, health and community development through integrated mission. Lisa, a Canadian expatriate, has worked with the Army in Africa for 10 years—in South Africa with the divisional HIV/AIDS team, at a divisional training school, at Care Haven (a shelter for battered women and children) and, since 2005, with the all-Africa regional facilitation team. Geoff Moulton, assistant editor-in-chief, interviewed Ricardo and Lisa about their work in Africa.

We hear a lot about HIV/AIDS in Africa through the media. What's your take on the situation? Are things getting better or worse?

Ricardo: It depends on how you define better. There's more money coming into Africa than ever before, but it's not nearly enough. More access to anti-retroviral drugs is good, but health facilities are still woefully understaffed. Even if countries have access to treatment, they don't have the infrastructure to deliver it. The problem is compounded by tuberculosis, malaria and lack of food. Antiretroviral drugs are toxic, so if you aren't getting consistent nourishment they'll possibly kill you faster than AIDS.

In some countries we're seeing a levelling off of the pandemic, so fewer people are becoming infected. But as the epidemic shifts, new concerns arise. For example, what does South Africa do with its six million orphans in the next decade? Their parents died from AIDS and many are being cared for by their grandparents. But what happens if the present generation of young people becomes infected with HIV? Who will be left to look after their children?

Some countries are beginning to see the impact of HIV/AIDS in terms of its economic effect. In South Africa, 33 percent of the working population is HIV-positive. What happens when those millions of people become too sick to work and aren't eating enough to take medication? I wouldn't say the situation is getting better. Rather, it's shifting and becoming more complex.

What about the social stigma? Is that still a problem in Africa?

What about the social stigma? Is that still a problem in Africa?

Ricardo: It's incredibly difficult to admit that you're HIV-positive. In many places it is closely associated with witchcraft and the supernatural. Churches are also perpetuating the stigma and discrimination. There are all kinds of moral labels being attached to HIV infection and to HIV intervention. Some churches still refuse to discuss the safer sex options because of the moral implications. So the stigma is still prominent.

Eight out of 10 people who are infected don't know it, partly because they're scared to come forward for testing. That makes treatment extremely difficult for governments and agencies such as the World Health Organization. They try to respond as best they can but are limited because their approaches are based on external interventions. What's missing is a long-term community response, where communities and neighbourhoods are comfortable enough to discuss and change their own behaviour. It's the only thing that will turn the tide of the pandemic—nothing else will make a difference.

We don't come to offer easy answers, but rather a willingness to be alongside others and discover together the grace that leads us to fullness of life

How is The Salvation Army helping with this crisis?

Ricardo: During the ecumenical pre-conference at the 2006 International AIDS Conference in Toronto, UN AIDS head Peter Piot said that although there are few if any success stories in more than 25 years of HIV in the world, two organizations are worth mentioning. One is the Roman Catholic Church with its example of hospice care for the terminally ill. The other is The Salvation Army for its model of how to link home care with prevention.

The Army understands that it's not just about medical intervention or professionalized care. It's about meeting people in the place where they live, making decisions in the context of the family, between neighbours and in the community. That goes beyond medical care—it's about social and psychological support. When people can be alongside one another they can feel deeply concerned enough for one another and decide to change. This accompaniment of communities in life—we think of it as integrated mission—has been the most defining contribution of The Salvation Army. However, as more and more money becomes available, the distinctiveness of the Army's approach will become more difficult to maintain.

What problems does money cause for your work?

What problems does money cause for your work?

Ricardo: The well-intentioned but misguided influx of money is cutting the legs out from under this distinctive dimension of the Army's response. The U.S.A. has poured billions into HIV/AIDS in Africa, but agencies are often limited to prescribed campaigns and program approaches if they want to access that money. That doesn't validate the idea that communities can come together with counselling support to talk, make decisions, change and give hope.

Defending something as simple as being alongside people and believing they can change is tough, because it sounds too easy. But we have the evidence to prove it works. We've found that ordinary people can make a difference if they are supported through a counselling presence. The champions in these African villages are, for instance, grandmothers who have lost five or six of their own children to HIV, but are caring for orphans with no money. They depend on the good will of their neighbours, who also have no money, yet somehow miraculously make it through.

Can you give examples of how communities have rallied together?

Ricardo: Chikankata Hospital in Zambia is where the Army's HIV/AIDS response first surfaced. In the early 1980s, people were dying and no one understood why. The hospital was filling up quickly. The doctors and nurses couldn't stem the tide. Because Chikankata had experience with leprosy and understood the importance of family connection and support, they decided to approach this emerging disease in the same way. They followed patients back to their homes to talk at a family level about loss and grief and what it would mean to feel hopeful again. In the process, they discovered that families knew more than the professionals did. They could identify sources of infection as well as things that made them feel well.

As the community came together to talk about the behaviours that were putting them at risk, they realized change was needed. One of the first decisions was to end the practice of “widow cleansing,” where a widow was taken into the brother-in-law's family as a means of social protection. Part of this involved a ritual cleansing of her husband's spirit through sexual intercourse with the brother-in-law. The Zambians realized this practice was making them sick. Over a period of time, through conversations at the community level, villages decided to stop practising sexual cleansing and thereby reduced their risk of HIV infection.

We have to risk being in the place where people make their most intimately personal decisions about life

In Mozambique, the Army team visited a village for an hour and spoke with teenage boys, girls and grandparents in the marketplace. When the issue of HIV came up, no one wanted to acknowledge it until an older woman stepped forward and said, “We know what's going on. We're losing our husbands—the young girls are stealing them.” It opened up a dramatic conversation. The husbands would work through the week, receive their wages and return to spend the entire weekend drinking in the village bar. They became sexually involved with young girls who deliberately hung around the bar to earn money through prostitution. They would contract HIV and then go home to their wives where they would be abusive, demand sex and spread the infection.

It was the first time anyone had ever named that issue between the generations, and it was like opening a powder keg. Everyone knew about it, but only when someone was brave enough to speak the truth did everyone jump into the conversation. The girls in particular responded, “Do you think we want to do this? If there was another option we would behave differently.”

As a result, a few things happened. The young men in the village decided that it was not safe for young girls to walk around after dark unaccompanied. They volunteered to walk them home after dark so the girls were not distracted or accosted. The older women and the rest of the community applied pressure on the bar to close by 8 p.m., not giving enough time for the men to get inebriated and abusive.

The boys approached the village chief about a piece of land to create both a vegetable garden where the girls could work for steady income and a soccer pit where the orphans could play. At the end of the soccer match each Saturday, community leaders would meet with youth to talk about life, the future, decisions about relationships and ambition. As they gained confidence, the surrounding villages began to see the change and invited this community to help them do the same thing in their villages.

So one conversation made the difference?

So one conversation made the difference?

Ricardo: The principle is universal—we have to risk being in the place where people make their most intimately personal decisions about life. Understand that people don't exist in isolation. They make decisions collectively and communally. And if there is a way to connect them for conversation in a non-intimidating, non-judgmental, non-prescriptive environment, they will choose the good way. I think that's a distinctive for The Salvation Army: we're not cynical enough to believe that people will always choose the worst option. We believe the optimism of grace—that given a chance people will choose the good. Why would they choose anything else?

In Canada we're accustomed to a more traditional approach to service delivery. How could integrated mission work here?

Ricardo: I define words “traditional” and “modern” somewhat differently in terms of ministry. Integrated mission is the most traditional Salvation Army approach to ministry that there can be. That was our genesis—living in community with people, believing that the grace of God can be discovered if you go to be where people are, as opposed to just designing something to bring them to you. That is who we are. It's the most traditional thing we've done, but it's not the most modern thing we've done. Our “modern” approach to ministry is driven more by our reputation as a service organization and, in many cases, we may have substituted good will and good works for incarnation and presence.

Integrated mission is not about an integration of services or departments. It's not structural or systemic. It's about the integration of ourselves as people into the reality of life with others. It has theological roots, because that's how Christ did ministry. He integrated himself into our world, which is the basis of our mission. If we get that basic practice right, it's really quite simple. It's not about program—it's about relationship with people. Mission doesn't happen as a function of what's offered inside the building. It exists when we get out and into the difficult, messy situations of community life. We don't come to offer easy answers, but rather a willingness to be alongside others and discover together the grace that leads us to fullness of life.

An older woman said, “We know what's going on. We're losing our husbands—the young girls are stealing them.” It was like opening a powder keg

Lisa: Compared with Africa, the Army in Canada has a lot of money, resources and reputation. If you ask people to donate, usually they will respond. There's money to hire people to do the job. There are social workers, outreach workers, all those things. And so the tendency in recent years is for Salvationists to simply support the mission by paying professionals to do ministry.

However, when I was growing up as a Salvationist in Canada, we got outside our buildings and ministered to people on the streets and wherever else we found them. As time has gone by we've gotten further and further away from that. When I was running a soup kitchen in Williams Lake, B.C., all my helpers were Catholic volunteers. These days, getting someone to do something for nothing isn't easy. Too often people expect to be paid for a service. I think some Salvationists have gotten into the habit of meeting together on Sunday to worship, but don't realize they are called to serve the rest of the week, too. Have we forgotten why we first signed up as soldiers?

Integrated mission is about taking yourself out of your comfort zone and going where the people are. But the message we're taking today is different than it used to be. Rather than “open-air” meetings where we preached at people, integrated mission is about sitting down as equals and having natural, day-to-day conversations. And it doesn't have to happen just in the slums. You can still have relationships with people in your neighbourhood—people at the bank, the moms at your school, the dads at hockey practice. It's just knowing how to start those conversations.

Ricardo: Unfortunately, many people see the concept of integrated mission as very humanistic—that it's about strengthening people, responding to social concerns and not explicitly gospel enough. I think that is a misconception. Integrated mission is about transformation, healing, abundant life, freedom, release and reconciliation. Those are gospel qualities, but because it's not as explicit as our traditional open-air meetings and campaigning, it seems humanistic and people back away from it a little.

Why is integrated mission so important?

Why is integrated mission so important?

Ricardo: We have to do it or else we lose who we are. The mission connection with other people, the participation in suffering, the incarnational approach—nothing else will keep us alive. For completely selfish reasons we have to do it, because we will die without it.

The church in the West rallies around the word “relevance.” But relevance is a misnomer because we cannot compete with the world. The world is always a better entertainer. If we're honest, many of us would rather go see a movie than go to church. But we can be responsive. It takes away the burden of having to compete. And it allows us to be ourselves with people, to have integrity. When you are responsive, you don't have to worry about being relevant—that takes care of itself.

In order to be responsive, we first have to learn from what is happening on the ground, in life with ordinary people. Why is it important to look beyond service delivery? Because we have to learn. The question is: Can we apply enough of what we are learning so that we keep changing and continue to be responsive?

Is there a particular Bible passage that resonates with you?

Lisa: Micah 6:8 says we must act justly, love mercy and walk humbly with our God. When people share their stories I am always moved. I feel what they're going through as if I were going through it myself. In one village I visited a widows' club where each month they saved enough to buy one widow a goat so that everyone had some income. They asked me to say something to encourage the women. Here I was, sitting on the mud floor of a hut with widows who had so little materially-speaking yet were so resilient and hopeful. The truth is, they were teaching me about how amazing God is. When life is difficult, you can become bitter and angry and shake your fist at God. Or you can choose to “walk humbly” with him.

Ricardo: For me, it's the passage in Hebrews 13:11-14 that speaks of Jesus as the high priest who finds himself outside the city gates, amid the outcasts, the lepers, the unclean. He presenced himself with them, and the instruction is for us to go and be with him in the place of shame, suffering and disgrace. This has profoundly shaped my understanding of integrated mission. It's not that the world is so desperately dark until one of us nobly emerges with the light and the truth. Rather, the reason we go into the dark places is because Jesus is there―and we go there to join him, because he hasn't abandoned those who suffer.

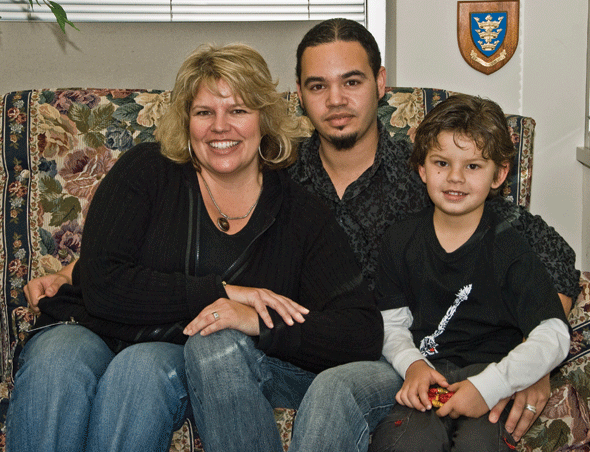

Photos: 1. Community conversations in Maputo, Mozambique; 2. Lisa and Ricardo Walters with their son Zachary; 3. Home visit to a family in Nigeria; 4. Facilitation team at the All-Africa Congress in Zimbabwe; 5. Young boys using machetes to collect firewood in Nigeria. Children who have lost both parents to AIDS often act as primary caregivers for younger siblings

Leave a Comment