The year is 1878. The setting: Coventry England. Posters and sandwich boards have been placed up and down the main street. If we look carefully, we can see the women coming toward us, dressed in black frocks and capes, with Quaker-like bonnets tied around their chins. We have time warped into an open-air meeting of The Salvation Army's Hallelujah Lassies. Their words ring out clear and plain: “Sinner, prepare to meet thy God! Heaven or Hell? Which will it be? Where will you spend eternity?”

The year is 1878. The setting: Coventry England. Posters and sandwich boards have been placed up and down the main street. If we look carefully, we can see the women coming toward us, dressed in black frocks and capes, with Quaker-like bonnets tied around their chins. We have time warped into an open-air meeting of The Salvation Army's Hallelujah Lassies. Their words ring out clear and plain: “Sinner, prepare to meet thy God! Heaven or Hell? Which will it be? Where will you spend eternity?”

It's certainly not a message that had been screened by standards of 21st-century seeker sensitivity. Yet, this sense of eternal focus defined early day Salvationists. Urgency of Kingdom perspective drove the spoken word. Lost sinners were in need of a Saviour. The day of eternal judgment awaited all of humanity.

In our pluralistic society, we have often struggled as Salvationists to understand what we are all about. Does the world still have a place for The Salvation Army, recognizing people's complacent response to religious expression? “Forget this pie in the sky about the sweet bye and bye,” says our neighbour down the street, struggling to pay bills and make ends meet. “We want us some Kingdom come right here and right now!”

Add to this the diminishing respect for the authority of the Church, and we must ask: Does the world still have room for an evangelistic movement that is earnestly focused on the importance of being prepared for eternity? Is this the kind of witness we are to be about? If we stood on the street corner, asking the same questions posed by early Salvationists, would people even listen?

I can imagine the scenario: “Excuse me, sir … yes, I know you've got errands to run today, but tell me, Heaven or Hell? What will be your eternal destination?” Or “Excuse me, ma'am … I see you are in a hurry. But when you've run out of e-mails to answer and appointments to keep, where do you see yourself: Heaven or Hell? What's it going to be?”

As we align our missional objectives with today's realities, we may be tempted to believe that the message of God's judgment will not sell by modern standards. And so we entertain other possibilities. Perhaps we become less aggressive. Perhaps we speak only of those things that bring comfort to our audience, for example, messages of love, joy, peace, hope and good news. We say, “Let this be why we exist as an Army.”

In response, let's hear the words of Catherine Booth: “There is no improving the future without first disturbing the present; and the difficulty is the willingness to get people to be disturbed.” Catherine argued that the great mission of early Salvationists was to be “God's great disturbers of the peace—to proclaim the unrelenting truths of a disturbing gospel.” People in Catherine's day mistakenly felt they could just continue their lives as usual, that nothing needed to change. Catherine believed in waking up sleeping sinners who were not conscious of their spiritual condition.

Reinforcing this perspective, Commissioner Theodore Kitching, close confidant of the Booths, said, “Show the people their sins,―remind them of their coffins—make them think of the judgment bar—tell them of the cleansing blood-picture, the bliss of the saved and the agony of the lost.” If we define ourselves by such a message that so forthrightly speaks of Hell's horrible realities, will we do more harm than good? Will people listen or will we alienate our audience? Can we strike a balance?

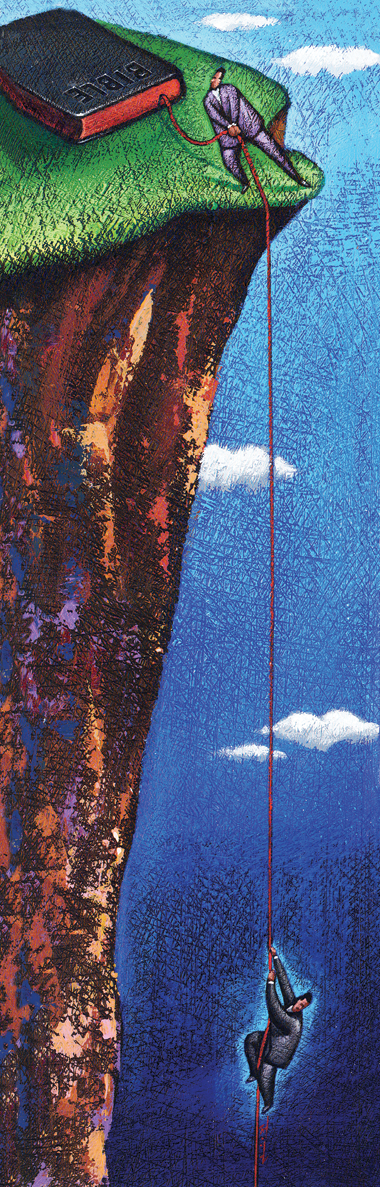

We will only begin to answer these questions when we recognize the importance of proclaiming the fullness of the gospel. Historically speaking, The Salvation Army has been defined by eternal goals. A suffering world still needs voices that are whole-heartedly devoted to this emphasis. The world still needs to know about the bliss of the saved and the agony of the lost. Options for eternal destination have not altered. Spiritually speaking, we are only tracking two possible ending points—Heaven or Hell. Shaped and influenced by the waves of 19th-century American revivalism, early Salvationists knew to remind people what was really at stake: Where would they spend eternity? Where will we?

Assessing the current climate of the Christian Church, Michael Quicke, C.W. Koller Professor of Preaching at Northern Seminary, Lombard, Ill., identifies the need that motivates us as an Army. He says, “In too many places, [Christian faith] has been reduced to an anemic, religious non-event. Faint is its power to proclaim an alternative reality … missing is its subversive way of challenging the status quo…. There is too little courage and too much safe predictability, too little confrontation of evil … and too much soothing of the already convinced.”

If we take any insight from our history as a Christian movement, we will know the strength of our ministry has been marked by a mandate to disturb and unsettle those focused on the temporal. We don't have to be abrasive or repelling in how we share our message. Rather, the key is to recognize our divine appointment to get the world's attention. Rather than hammering people over the head with a “Heaven or Hell?” ultimatum, it may be more effective to invite people inside the experience of faith we have discovered for ourselves. This will only be achieved through the authenticity of our witness, our genuine love and compassion for the lost and a passionate energy fuelled by the leading of God's Spirit in our lives.

Recently I had a conversation with a young mother who was grappling with the decision about who to ask to be godparents—spiritual mentors and caregivers―to her two young daughters. While the first option promised nurture and care for her children, it was not a Christian environment. Her second choice offered a home where her girls would be raised in the ways of faith. “In the end, it's a no-brainer,” she said. “Why wouldn't I pick the option that gives my girls every chance of going to Heaven?” It reminded me again of all we are about. We are not only an Army bringing hope today, we are bringing hope for eternity.

William Booth summed it up best when he said, “My object is to get my audience right with God for time and eternity.” While this task may not be easy, Hell and eternal judgment remain real words in our theological dictionary. So, too, are the redeeming words of God's love and grace. The importance of this balanced message remains one more reason why the world needs the continuing ministry of The Salvation Army.

Major Julie Slous is the corps officer at Heritage Park Temple in Winnipeg. She has a doctorate in ministry from Luther Seminary in Minneapolis, U.S.A.

Leave a Comment