From the moment Jesus was approached by Jairus, the crowd grew in anticipation. Jairus was a leader of the synagogue. He also had a 12-year-old daughter who was dying. The urgency of his request, however, was interrupted by a woman who had been hemorrhaging for 12 years. Jesus healed her body and her place in the community, but his response to Jairus was delayed. The journey resumed, and they reached the home where Jairus' daughter lay. “When [Jesus] came to the house, he did not let anyone enter with him, except Peter, John and James, and the child's father and mother” (Read Luke 8:40-56 NRSV).

From the moment Jesus was approached by Jairus, the crowd grew in anticipation. Jairus was a leader of the synagogue. He also had a 12-year-old daughter who was dying. The urgency of his request, however, was interrupted by a woman who had been hemorrhaging for 12 years. Jesus healed her body and her place in the community, but his response to Jairus was delayed. The journey resumed, and they reached the home where Jairus' daughter lay. “When [Jesus] came to the house, he did not let anyone enter with him, except Peter, John and James, and the child's father and mother” (Read Luke 8:40-56 NRSV).

At the moment of its greatest expectation, the crowd was excluded. We don't know what Jesus said, but his words must have jarred them. They had come to know Jesus as a public figure. They listened to him teach from a boat; they watched him respond with amazement to a Roman centurion. This same crowd had just observed how Jesus drew a woman from anonymity into the public space. So it seemed fitting that they follow Jesus into the house of Jairus. But Jesus refused their admission. This was a moment just for the parents and selected disciples. This most public Saviour protected a family's privacy.

It's instructive to read through Luke's Gospel with an eye to issues of privacy. When Jesus prayed, he sought to be alone (see Luke 4:42; 6:12). When the apostles returned from a time of ministry, “he took them with him and withdrew privately” (9:10). In another moment of teaching with his disciples, “Jesus said to them privately …” (10:23). Yet Jesus also taught and healed publicly. He was crucified in a public space. And his Spirit creates a public Church. Paradoxically, this most public Jesus creates moments and spaces needing privacy.

Early on in life, I learned some of the public dimensions of Christian faith. My father played trombone in the old Hamilton Citadel Band in Ontario. On Sunday nights I ran alongside my dad as the band marched up James Street. I learned that our faith belonged in the streets of the city. Years later, as a Salvation Army officer, I also learned that there were important private dimensions to Christian faith. Conversations that took place in a hospital room or with cadets in my office, had confidential dimensions. There have been times when it was necessary to close the door and keep others out.

Some situations are made public with a little laughter. When my wife and I worked with others to establish the first corps in Fort McMurray, Alta., various leaders were invited to the opening of the building. At one point in the weekend we invited them to our home for a snack. Just before leaving I put on my Salvation Army uniform cap. Our five-year-old son looked at me and innocently asked, “Dad, what's that on your head?” Our good friend, Commissioner John Waldron, simply smiled.

Unfortunately, the erosion of necessary privacy is having disastrous consequences in our time. Cellphones, Facebook, Twitter and the tools of the Internet have effectively wiped out the notion of privacy. Some of this has obviously been helpful in what can be “cultures of secrecy.” But our desire to have 15 minutes of fame can also destroy the integrity of privacy, and human lives with it.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks has expressed his own convictions on this matter: “A world without strong networks of family and community is a world of strangers. It fails to answer to our need for recognition, emotional intimacy, the 'listening other.' In such a world people do strange things. They proclaim their principles on T-shirts. They wear designer labels on the outside. They confess not in the privacy of the confessional but in the publicity of Oprah Winfrey-style television programs…. The distinction between public and private becomes blurred … [and] life takes on the culture of public spectacle” (The Home We Build Together, emphasis mine).

Jesus refused to turn this moment with Jairus and his family into a public spectacle. Making clear the lines between public and private is an act of compassion. It's a clarity much needed in our time.

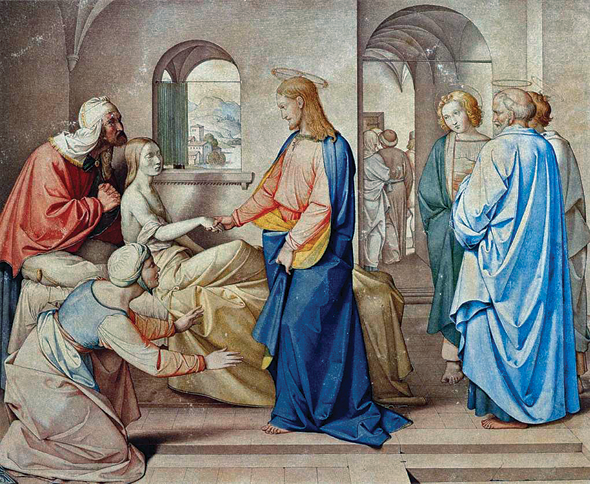

Illustration: Christ Resurrects the Daughter of Jairus, Friedrich Overbeck, 1815

Major Ray Harris is a retired Salvation Army officer. He enjoys watching Corner Gas reruns and running in Winnipeg's Assiniboine Park.

Major Ray Harris is a retired Salvation Army officer. He enjoys watching Corner Gas reruns and running in Winnipeg's Assiniboine Park.

Thanks for taking time to respond, and to keep the conversation going. Interestingly, I took in a university performance of the Diary of Anne Frank last night, and was deeply moved by its portrayal of confined individuals and families trying to create private spaces in a world of conflict.

You have raised a most important matter, and that is what we need to do to help create appropriate private spaces in our time. Let me suggest a few things, and invite your [and others'] response:

1] I think it's important for each of us to create private times and spaces for ourselves. Some might name this "solitude." It seems to me important that I value privacy even as I seek to create it for others. Over the years that has come to mean early morning commitments to myself.

2] In my role as spouse, parent and officer, I have learned [sometimes the hard way] that I need to ask questions: Who needs to know this? When? By what means"? What is at stake if this is kept private? Is there a danger that privacy becomes a cover-up? What is good for the individual concerned, and what is good for the community? You can see that there is no simple button to push, but questions need to be asked.

3] On the other side of the coin, when I have had to ask people to trust my silence on a matter, I know I am asking them to trust my integrity. There have been times in positions of leadership that I cannot say everything I know. It is possible for me to betray that trust, but that is one of the difficult challenges in leadership.

Let me stop there, and invite you to add, subtract etc.

Blessings - Ray