We have a deep desire to make sense of tragedy and suffering. Parents seek some glimpse of meaning when a son is killed in an automobile accident. Fallen soldiers are repatriated with rituals that convey significance. The world tries to make meaning of an earthquake that devastates the nation of Haiti and its capital city, Port-au-Prince. The instinct to interpret tragedy is strong. However, our attempts to find meaning seldom do justice to the suffering that has taken place. Even Jesus recognized this.

We have a deep desire to make sense of tragedy and suffering. Parents seek some glimpse of meaning when a son is killed in an automobile accident. Fallen soldiers are repatriated with rituals that convey significance. The world tries to make meaning of an earthquake that devastates the nation of Haiti and its capital city, Port-au-Prince. The instinct to interpret tragedy is strong. However, our attempts to find meaning seldom do justice to the suffering that has taken place. Even Jesus recognized this.

On one occasion a report was brought to Jesus about Pilate's slaughter of Galileans in the Jerusalem temple (see Luke 13:1-9 NRSV). Those who communicated the report to Jesus wanted to make sense of this atrocity. Could it be that this tragedy was the result of the sufferers' own sinfulness? Was their suffering an act of God's judgment?

Instead of responding directly, Jesus posed questions to them: “Do you think that because these Galileans suffered in this way they were worse sinners than all other Galileans? … Or those 18 who were killed when the tower of Siloam fell on them—do you think that they were worse offenders than all the others living in Jerusalem?” Then he answered his own questions: “No.” Jesus jarred their assumptions by refusing to draw a straight line between suffering and sinfulness.

Sometimes human suffering is the result of sinfulness; the deceitfulness of some investment firms, for example, has contributed to the suffering of their clients. But Scripture permits no clear connection between those who suffer and their sinfulness. In John's Gospel, for instance, Jesus refused to lay the responsibility for a man's blindness either at his or his parents' doorsteps (John 9:1-12). The Bible does not allow us to connect tragedy directly to our sinfulness.

The Church has often struggled to understand how God is related to suffering. There have been times when the Church has attempted to inoculate God from suffering in such a way as to make him irrelevant, if not inexcusable. But as he contemplated the sufferings of Jews in Nazi Germany, Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote from his prison cell that “only the suffering God can help.” It is the Christian conviction that in the life of Jesus we see more clearly the character of God who walks “the road marked by suffering.”

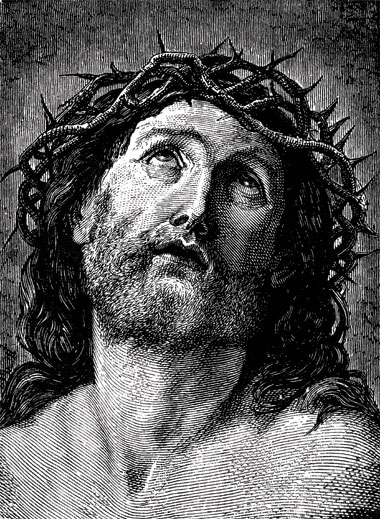

Through the life of Jesus we glimpse a God who touches the leper when healing him (Luke 5:12-16), and who straightens not just a woman's back but an understanding of the Sabbath that also was bent (Luke 13:10-17). Matthew's Gospel summarizes the healing ministry of Jesus by drawing on the text of Isaiah: “He took our infirmities and bore our diseases” (Matthew 8:17 NRSV).

These actions of Jesus find their climax in the cross where, in the Apostle Paul's words, “God was in Christ reconciling the world unto himself” (2 Corinthians 5:19 KJV). Christians understand God to be One who is not detached from suffering, but who fully engages it. Thus we seek not so much to explain suffering as to engage it in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Instead of trying to make meaning out of these tragedies, Jesus instructed his questioners to “repent,” to turn their lives around 180 degrees so that they bear fruit “worthy of repentance” (Luke 3:8 NRSV). This is where we can make meaning, not so much in comprehending tragedy but by engaging its suffering in the name of Christ. By the grace of God we can turn our lives around so that our character and actions begin to reflect those of Christ.

Majors Geoff and Sandra Ryan served as officers in Russia for nine years. At one point Geoff spent time in war-torn Chechnya and came face-to-face with incredible suffering. His response to horrific pain was to conclude: “The question is not to ask 'why?' but rather, 'what now?' There is no point on speculating why [evil] exists and why God allows it. Far better to acknowledge the facts before one and deal with them” (Sowing Dragons: Essays in Neo-Salvationism).

The instinct to interpret suffering is strong. There are times, however, when attempts to make sense of suffering only add to it. What we can do is to respond in the name of Christ to those who suffer. This, too, is an act of interpretation.

Illustration: Ecce Homo, Guido Reni, 1620. “He took our infirmities and bore our diseases”

Major Ray Harris is a retired Salvation Army officer. He enjoys watching Corner Gas reruns and running in Winnipeg's Assiniboine Park.

Major Ray Harris is a retired Salvation Army officer. He enjoys watching Corner Gas reruns and running in Winnipeg's Assiniboine Park.

grace... Kathie