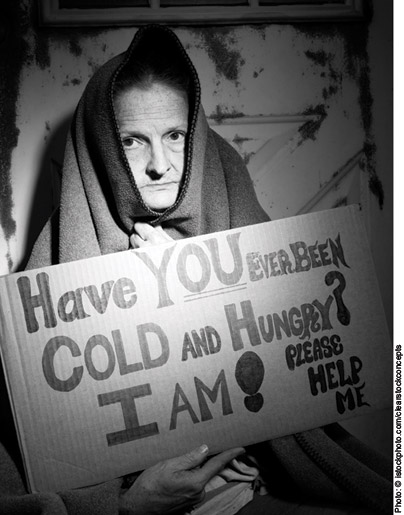

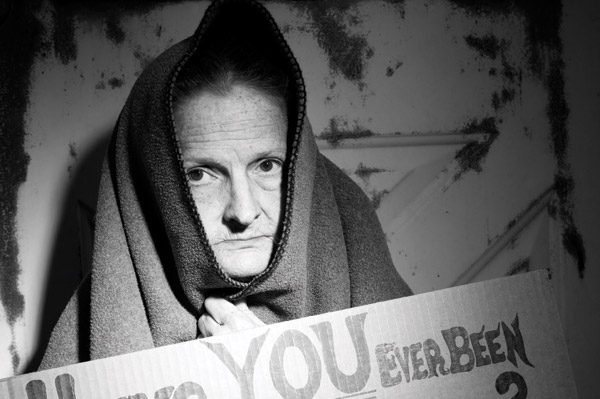

All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good people to do nothing.” While political theorist Edmund Burke (1729-1797) had a point when he made this assertion, one has to question what factors really shape society's “do nothing” mentality. Is it lack of insight into societal struggle, insufficient resources or perhaps a lack of confidence in our own ability to really make a difference?

All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good people to do nothing.” While political theorist Edmund Burke (1729-1797) had a point when he made this assertion, one has to question what factors really shape society's “do nothing” mentality. Is it lack of insight into societal struggle, insufficient resources or perhaps a lack of confidence in our own ability to really make a difference?

We find evidence of this dilemma within our own Salvation Army history. William Booth had experienced a sleepless night following a revelation that men were sleeping out in the cold under the city bridges. The Founder's conscience had been quickened. How could he sleep in a warm bed while others suffered outside? “Did you know about this?” William asked his son, Bramwell, the next morning. “Yes, General,” Bramwell replied. “And you did nothing?” the Founder questioned.

Bramwell had a quick defence. The Salvation Army could not undertake to do everything that ought to be done in the world. As well, one had to be cautious that charity was not expressed indiscriminately. “Oh, I don't care about all that stuff!” the Founder said. “I've heard it before. But go and do something! Do something, Bramwell, do something!”

It is the tension between the phrases “do nothing” and “do something” that calls for our attention as dignity workers in The Salvation Army. To understand our missional challenges, it is critical that we identify what informs our “do nothing” response. Perhaps Bramwell had a point. We can't undertake everything that ought to be done in the world. We must pick and choose what dragons we have the power to slay. The danger is that our response can become selective and conditioned by what project we deem to have the most potential for success. Consequently, that which requires risk-taking and hard labour may be passed over for that which seems easy or manageable.

There is also the perspective that says “we do nothing because we have nothing of value to offer.” Maybe this was the dilemma the disciples encountered in Luke 9:10-17, as they faced 5,000 people in need of food and lodging. Would they do nothing? Would they do something? What was within their power to give?

As Luke unpacks the scene, we see immense challenges. When was the last time any of us ever tried to make hotel reservations for 5,000 people? (Note: Luke's count only included the men. We can only guess how many women and children were also present!) When was the last time we tried to rustle up a few leftovers to feed this kind of a crowd? With no online connections to Google available to find accommodation in remote Bethsaida, the disciples found themselves with quite a situation on their hands. They finally went to Jesus (see Luke 9:12) and said, “Master, we've got a problem and here's what you need to do! You need to send this crowd away now so they can go to the surrounding villages and countryside and find their food and lodging because we are in a remote place.” Note the emphasis: the disciples told Jesus that he needed to do something! Not one of the Twelve was ready to assume a personal burden for this crowd.

What is wrong with this picture? At first glance, we might not think anything is misplaced. After all, Jesus was the greatest teacher and healer of all time. He'd had this crowd's attention for most of the afternoon. It was reasonable to expect Jesus to take care of this situation. Jesus, however, turned the tables and challenged the disciples to take care of the problem themselves. “You do something,” Jesus said. “You give them something to eat” (see Luke 9:13). Suddenly this became a teaching moment for the disciples as they were challenged to see how the needs of the masses were their problems to own and solve.

The disciples' response is classic: “But Jesus, we have only five loaves of bread and two fish.” Otherwise translated, “Jesus, that's about one loaf for every thousand people and we won't even begin talking about the fish. That pretty well takes us off the hook, doesn't it? Do the math, Jesus! What's in this basket is not going to feed this crowd!” Here we see another dilemma. Often our response to human need is inhibited because we place limits on the resources with which we have to work. Jesus had to be smiling and thinking, “OK, you just wait till I show you what can be done with what's in your basket!”

The disciples, however, weren't really grasping the big picture. Luke adds their after-thought when they suggested they could go out and buy food for the crowd (see Luke 9:13). I imagine Luke laughing heartily! Just where did these crazy disciples think they were going to buy food in remote Bethsaida? What corner store at the intersection of nowhere and nowhere was going to have enough provisions to feed over 5,000 people? Where did these disciples reasonably think they could buy this food?

Then add into this story one other significant speed bump. Look back to what Luke tells us in verse 3 of this chapter. Jesus commissioned these disciples to declare their complete solidarity with the poor and to place their total trust in him to provide for their needs. And so Jesus said, “Take nothing for the journey—no staff, no bag, no bread, no money, no extra shirt.” So who would buy food for the masses, given the disciples' pockets were empty?

The reality of the moment, however, was that the disciples actually did have the power to make a difference. Luke told us this at the very beginning of the chapter, that Jesus had given the Twelve the power and authority to drive out demons, to cure diseases, to preach about the Kingdom of God and to heal the sick. They had been resourced for this very moment in Bethsaida, but failed to see what they could contribute.

Packing up the picnic baskets in Bethsaida and taking inventory of all that was left behind, we recognize that “little is much when God is in it.” Our struggle to “do nothing” versus “doing something” will continually be undermined by the evil one who wants us to believe that our gifts and resources are not enough. Christ calls us as dignity workers to take fresh inventory of what we have to offer our community. We may not have immediate solutions to homelessness, gang violence or the malnourishment and neglect of children in our neighbourhood. But through our conversations, our relationships and our interactions, we can draw attention to the injustices surrounding us. It all begins as we start to speak our own story of faith into the circumstances before us.

Evil will continue to flourish if good people do nothing. But if good people do something, imagine how this could change the landscape of our country. While our “doing something” should be calculated and intentional, let us not underestimate the power of the five loaves and two fish that may already be sitting in our baskets.

Major Julie Slous, D.Min., is a corps officer, with her husband Brian, at Winnipeg's Heritage Park Temple. She also serves as adjunct faculty at the College for Officer Training.

Leave a Comment