For the departure of the delegation, The Salvation Army arranged a send-off like no other. A group of Salvationists, including the Canadian Staff Band which was playing in the parade, marched down Yonge Street to Union Station. The Empress was leaving for England from Quebec City at about 4:30 p.m. the following day, Thursday, May 28.

It was a happy time for those members of The Salvation Army who were planning to attend the congress. After all, 1914 had been billed by the Army as “a year to remember.” Excited crowds of people cheered and waved handkerchiefs to encourage the exuberant passengers as they boarded the train heading for Quebec City.

When the Unthinkable Happens

The Empress, owned and operated by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), was a twin-screw steamer that sailed on its maiden voyage from Liverpool, England, to Quebec City on June 29, 1906. Over the course of eight years, the ship brought thousands of immigrants to Canada's shores.

While the ship had an impeccable safety record, more than a few passengers had the fate of the Titanic on their minds as they prepared to embark for England. Barely two years before, the supposedly “unsinkable” Titanic, at that time the largest ocean liner ever built, had gone down after hitting an iceberg in the North Atlantic with the loss of more than 1,500 passengers and crew. People were understandably still quite jittery about transatlantic crossings.

But the captain of the Empress, Henry George Kendall, assured the passengers that there were enough lifeboats on the ocean liner to accommodate 2,000 people—more than adequate for the Empress' 1,477 passengers and crew. Those with fears were relieved, especially when they were told that the Titanic took 2½ hours to sink. Even in the event of the unthinkable, they reasoned, surely this would be more than enough time to get off the ship safely.

The Empress' captain, Henry George Kendall (front, left) and his bridge crew

The Empress' captain, Henry George Kendall (front, left) and his bridge crew

Heavy Blow

On the first evening of embarkation, everyone retired to bed happy and satisfied. The St. Lawrence River was calm and there was a sense of completeness to a full day of travel and activity.

After departing Quebec City, the first stop was Rimouski, Que., for the mail exchange. Then the Empress began her journey to the second stop, Pointe-au-Père, Que., where the river pilot who guided the ship in and out of harbour was dropped off. Now it was full speed ahead.

However, vision soon became badly impaired by thick, unrelenting fog, and heavy smoke from forest fires that were raging in the southern part of the province.

At 1:55 a.m. Friday morning, May 29, 1914, less than 24 hours after the grand farewell, the Empress of Ireland was rammed by the Storstad, a Norwegian collier carrying a shipment of coal to Montreal, tearing a gaping hole in her starboard side.

As the Special Disaster Number of The War Cry stated, the sequence of events was cruelly swift: “a gentle bump and silence, a low heeling of the deck, a rushing up a perpendicularly sloping stairs, a vain attempt to launch lifeboats, a rushing in of foaming, icy water and 1,300 human beings struggling like a school of minnows.”

Sadly, the Empress listed so quickly that most of the passengers and crew were unable to reach safety. The Empress sank in a mere 14 minutes, and 1,012 passengers and crew were killed outright or drowned.

Of the 124 Salvationists who lost their lives on the Empress that fateful morning, 29 of them were members of the Canadian Staff Band. Other notable losses included the territorial commander, Commissioner David Rees, Colonel Maidment, chief secretary for the territory, Adjutant Edward Hanagan, bandmaster of the Canadian Staff Band, and their wives. The editor of The War Cry, Brigadier Henry Walker, perished along with much of the territorial headquarters' staff. It was a heavy blow to the Canadian Salvation Army.

The Canadian Staff Band, taken just before the voyage that claimed all but 10 of these men

The Canadian Staff Band, taken just before the voyage that claimed all but 10 of these men

Sorrowful Tribute

The news came quickly to a shocked nation. And while the tragedy reverberated throughout Canada, it was felt the hardest by the Army.

Before breakfast, territorial headquarters in Toronto was abuzz with officers trying to find out anything they could about the sinking of the Empress of Ireland. Surely there must be some mistake?

At first, Canadians were told that everyone was safe. Cheering greeted the glorious news but before long, as the story continued to unravel in the early dawn, there could be no denying the reality of the sinking.

The horrible truth was posted on the office windows at territorial headquarters. Some refused to believe it. As the people waited for better news, a revised notice was posted. Out of a total of 1,477 passengers and crew, only 465 survived.

Two hundred and thirteen bodies were placed on the dock at Rimouski, then transferred to the cruise ship Lady Grey and taken to Quebec City for identification by relatives. The bodies were carefully lifted off the deck of the

Lady Grey and respectfully placed in the large shed at Pier 27, which was temporarily set up as a mortuary.

The CPR made every attempt to make this process as painless as possible. A few more bodies were found and sent on to Quebec City on the cruise ship Lady Evelyn. Some bodies were sent directly from Rimouski to different parts of Canada, having been identified earlier. Yet 60 bodies remained unidentified. The CPR arranged for them to be buried at Rimouski in graves marked “Unknown.”

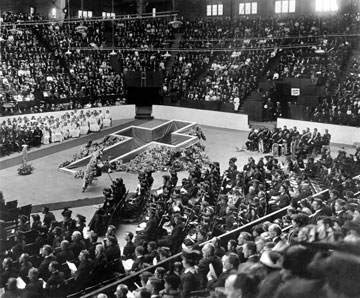

Sixteen Salvationists were buried in Toronto's Mount Pleasant Cemetery. More than 7,000 Salvationists attended a public funeral service at the Mutual Street Arena followed by a processional along Yonge Street, a distance of about five kilometres. The Toronto Mail and Empire reported on the front page in large print that this was the “GREATEST FUNERAL EVER HELD HERE.” It was estimated that more than 150,000 citizens watched the processional. Also in attendance was a composite band of 100 musicians from various corps.

Early in June, The Salvation Army held three more memorial services, one at the Mutual Street Arena and two at Massey Hall. Each service was packed to overflowing, a fitting tribute to all those who drowned on the Empress.

Public funeral in Toronto for the Army victims of the sinking

Public funeral in Toronto for the Army victims of the sinking

Lest We Forget

The world knows all about the Titanic and its unfortunate accident but very few are aware of the sinking of the Empress. Why is this so?

Timing. In scant months, the First World War broke out, consuming the headlines of the world for the next four years. The Empress' frightful misadventure was relegated to the back pages of the newspapers, if at all, and its story eventually faded from public consciousness. Succeeding generations rarely heard of the Empress.

But many in The Salvation Army did. Every year a memorial service has been held in May at the Salvation Army gravesite in Mount Pleasant Cemetery. It honours all those who drowned on the Empress of Ireland but particularly the 124 Salvationists who perished. The tragic sinking of the Empress of Ireland 100 years ago in the early hours of May 29, 1914, will never be forgotten. And it remains the largest peacetime marine disaster in Canadian history.

My grandfather and his father would have been on board (along with the rest of the Peterborough Corps Band) had they not found a slightly cheaper fare on another ship. Their “skin-flint bent” saved them (and me!!). Their corps band filled some of the Congress assignments left vacant by the tragic loss of most of the Canadian Staff Band.