Modern medicine offers many good gifts. Doctors routinely perform life-saving operations. Blood can be transfused, organs can be donated for transplantation and vaccines can prevent outbreaks of deadly diseases such as smallpox and measles. It is said that with enough time, money and expertise, medical research will help us conquer multiple sclerosis, dementia and cancer.

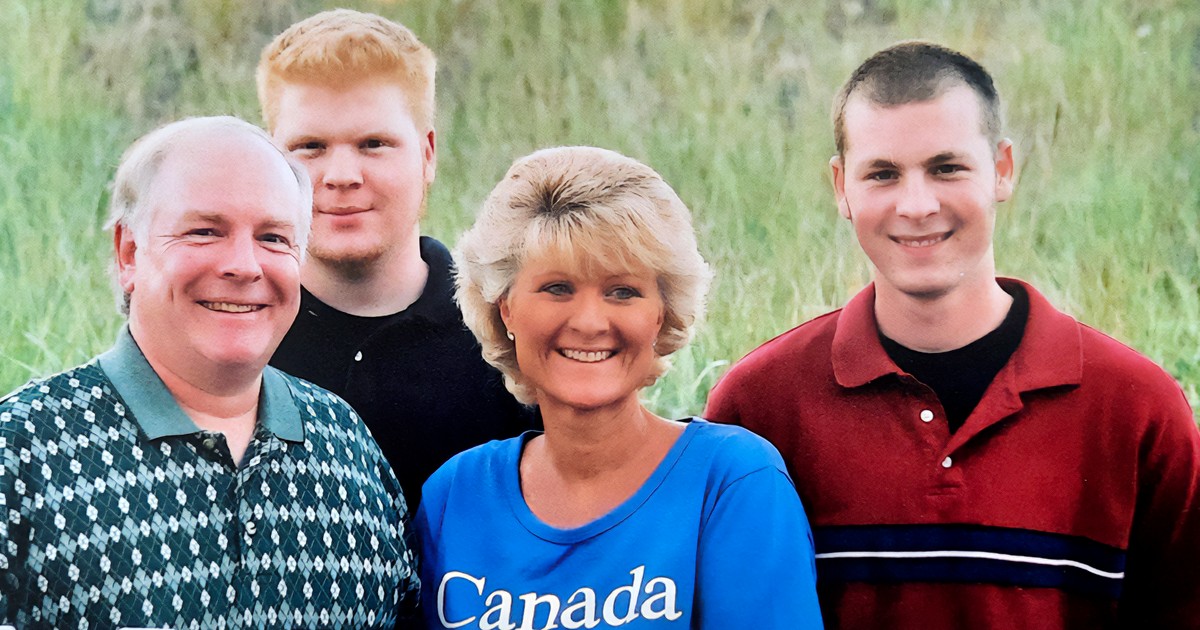

I have benefitted from advances in medical research. A cancer diagnosis put me on a difficult path of treatment—surgery, radiation therapy and a regimen of three chemotherapy drugs—that took well over a year. But it gave me a second chance to continue my vocational work at The Salvation Army Ethics Centre; a second chance to love the ones who are closest to me—my husband, my two children, my parents and my parents-in-law. Medicine has given me a good gift.

This experience made me ponder how people are affected by medicine in ways other than the physical. The extraordinary advances made in medicine have played a large part in nurturing the conviction that we can overcome any setbacks. We have even come to expect miracles.

Praying for a miracle is not wrong. But, in my view, medicine can call us toward the wrong kind of miracle. It is a myth that medicine can cure all ills and eliminate all afflictions. And the more that medicine promises, the less it seems we are able to tolerate the idea of suffering. Who could blame someone with early-onset ALS or Alzheimer's for being deathly afraid of the twisting and cramping of their muscles and their memories? Not me.

Even so, I don't think we need cure. I think we need healing.

One thing I have learned from palliative experts, both in the field and between the pages, is that there is a difference between curing and healing. Health is related to the word “wholeness” or the state of being well. Healing is a renewal of health or wholeness. This doesn't mean medicine has no place in health and healing. But medical treatment is only part of what is required. Healing does not always mean the elimination of suffering. Sometimes healing is about making suffering endurable.

The Witness of the Early Christians

In order to understand this concept of healing more fully, perhaps we can take a lesson from the early Christians. In his book The Rise of Christianity, sociologist Rodney Stark chronicles how two epidemics—perhaps smallpox or measles—that swept through the Roman Empire caused the church to grow.

The first of the plagues, the Antonine Plague, surfaced in 165 CE. It is estimated to have wiped out approximately one third of the population. The plague of Cyprian, occurring nearly a century later, yielded similar mortality rates. The words of Bishop Cyprian in his tract “On Mortality” describe the horrendous symptoms of this disease:

“That the bowels, relaxed into a constant flux, discharge the bodily strength; that a fire originated in the marrow ferments into wounds of the fauces; that the intestines are shaken with a continual vomiting; that the eyes are on fire with the injected blood; that in some cases the feet or some parts of the limbs are taken off by the contagion of diseased putrefaction; that from the weakness arising by the maiming and loss of the body, either the gait is enfeebled, or the hearing is obstructed, or the sight darkened….”

Stark's description of the fallout of the two plagues is equally distressing. The best Greco-Roman medical science of the day failed in its efforts to prevent contagion or provide a remedy. People stopped visiting one another. When they came across sick friends and neighbours, they went the other way. When family members showed signs of illness, they were tossed out of their households to die in the streets. Communities and cities collapsed. Those who remained alive found their society had been upended.

Except for the Christians.

These early Christians were bound by an ethic of love and self-giving. They understood that the love Jesus showed them was the love they were responsible to show others, even in the worst of times. They stuck together, risking and often losing their lives by caring for the ill among them.

These Christians didn't offer the medical practices of the Roman physicians which, while sophisticated, had proven ineffectual. But it wasn't long before they found that basic, attentive nursing care—practices as simple as providing food, water, a place to rest and human presence—helped a number of Christians recover.

Not all of them were spared from death. Most suffered. But their compassionate care helped solidify the community of faith. Christians were not ignorant of the deadliness of the plagues. Yet in Christ they were one body. They were called to build each other up even in the onslaught of suffering.

Moreover, these Christians were able to fulfil this responsibility because they had spiritual resources at hand. They knew they were part of something bigger: the kingdom of God. Theirs was a treasure that could not be infected. And this, in Stark's opinion, made it easier for them to cope in the midst of contagion. He speculates that unity, compassion and belief in life beyond death were factors that contributed to the higher rate of survival experienced by the Christian population. This was a miracle!

The Growth of the Church

But there's more. The way the Christians cared for others also had an impact on the non-Christian population.

Christians tended to the health of many outside their faith, probably people who were their friends and neighbours. Why? Christians had nothing invested in paganism. The Jesus movement was a marginal, even obscure, group in the Roman Empire. But when afflicted pagans were abandoned by their own friends and family, the Christians remained, happy to nurse and comfort the vestige of an empire. They knew they were responsible to love all others as Christ had loved them. Stark believes such care cut the general mortality rate dramatically. And who is to say, he asks sincerely, whether it was the soup or the prayers that brought about recovery? This was a miracle!

Christian nursing impacted pagans in another way. Pagans heard the message of good news as they were cared for. These Christians believed in a God who loved them, an attractive feature that pagan religions didn't have. And pagans came to know God's love was true as they saw with their own eyes how many Christians had been delivered from the plagues. What is more, these Christians had jeopardized and sacrificed their own lives to care for people outside their faith. The plagues would result in mass conversion to Christianity.

These Christians knew they nursed at great risk and at great cost. But they had the courage to do so because their faith story was not ultimately threatened by the present reality of pain, suffering and death. They were witnesses of a different truth. Jesus had taken on the suffering of others and died alongside them. Although his suffering did not put an immediate end to human suffering, his Resurrection offered the promise of a transformed life: a life with no more pain, no more tears, no more death, no more mourning. Christians had been given an opportunity to help make others whole, healing those who suffered and died. These Christians, the converted pagans might have thought, had the power to transform suffering into a gift of God. This was a miracle!

God's Healing Work

What does this mean for us today?

In many cases, modern medicine can relieve what is sometimes called “pointless suffering.” I welcome this wholeheartedly. Suffering in itself is not good. Why would we subject ourselves to the effects of the Antonine or Cyprian plagues when vaccines can prevent such diseases?

Still, medicine cannot eliminate suffering. The source of suffering is deeper than human flesh. Healing is more than relief from physical pain and discomfort. It is the transformation of the whole person. This is the witness of the early Christians. Healing requires courage sustained by faith. I have found my faith sustained, in great part, by the people who have cared for me. Caring does not require expertise, only compassion. It often presents itself in mundane ways. Sometimes the mere gift of presence is enough to show someone they are loved by others and by God.

I started out by saying that I have been given the gift of a second chance. Medicine has not cured me. It has given me time. There is more suffering to endure. Still, in being loved by others, I have found solace. My suffering encourages me to suffer better with others as they suffer. This does not mean I am glad to have cancer. But in a world that does not always understand that suffering can be redeemed, I am convinced that the Christian community can be a healing presence. This kind of healing is the miracle for which I pray.

Dr. Aimee Patterson is a Christian ethics consultant at The Salvation Army Ethics Centre in Winnipeg.

I have benefitted from advances in medical research. A cancer diagnosis put me on a difficult path of treatment—surgery, radiation therapy and a regimen of three chemotherapy drugs—that took well over a year. But it gave me a second chance to continue my vocational work at The Salvation Army Ethics Centre; a second chance to love the ones who are closest to me—my husband, my two children, my parents and my parents-in-law. Medicine has given me a good gift.

This experience made me ponder how people are affected by medicine in ways other than the physical. The extraordinary advances made in medicine have played a large part in nurturing the conviction that we can overcome any setbacks. We have even come to expect miracles.

Praying for a miracle is not wrong. But, in my view, medicine can call us toward the wrong kind of miracle. It is a myth that medicine can cure all ills and eliminate all afflictions. And the more that medicine promises, the less it seems we are able to tolerate the idea of suffering. Who could blame someone with early-onset ALS or Alzheimer's for being deathly afraid of the twisting and cramping of their muscles and their memories? Not me.

Even so, I don't think we need cure. I think we need healing.

One thing I have learned from palliative experts, both in the field and between the pages, is that there is a difference between curing and healing. Health is related to the word “wholeness” or the state of being well. Healing is a renewal of health or wholeness. This doesn't mean medicine has no place in health and healing. But medical treatment is only part of what is required. Healing does not always mean the elimination of suffering. Sometimes healing is about making suffering endurable.

Healing is more than relief from physical pain and discomfort. It is the transformation of the whole person

The Witness of the Early Christians

In order to understand this concept of healing more fully, perhaps we can take a lesson from the early Christians. In his book The Rise of Christianity, sociologist Rodney Stark chronicles how two epidemics—perhaps smallpox or measles—that swept through the Roman Empire caused the church to grow.

The first of the plagues, the Antonine Plague, surfaced in 165 CE. It is estimated to have wiped out approximately one third of the population. The plague of Cyprian, occurring nearly a century later, yielded similar mortality rates. The words of Bishop Cyprian in his tract “On Mortality” describe the horrendous symptoms of this disease:

“That the bowels, relaxed into a constant flux, discharge the bodily strength; that a fire originated in the marrow ferments into wounds of the fauces; that the intestines are shaken with a continual vomiting; that the eyes are on fire with the injected blood; that in some cases the feet or some parts of the limbs are taken off by the contagion of diseased putrefaction; that from the weakness arising by the maiming and loss of the body, either the gait is enfeebled, or the hearing is obstructed, or the sight darkened….”

Stark's description of the fallout of the two plagues is equally distressing. The best Greco-Roman medical science of the day failed in its efforts to prevent contagion or provide a remedy. People stopped visiting one another. When they came across sick friends and neighbours, they went the other way. When family members showed signs of illness, they were tossed out of their households to die in the streets. Communities and cities collapsed. Those who remained alive found their society had been upended.

Except for the Christians.

These early Christians were bound by an ethic of love and self-giving. They understood that the love Jesus showed them was the love they were responsible to show others, even in the worst of times. They stuck together, risking and often losing their lives by caring for the ill among them.

These Christians didn't offer the medical practices of the Roman physicians which, while sophisticated, had proven ineffectual. But it wasn't long before they found that basic, attentive nursing care—practices as simple as providing food, water, a place to rest and human presence—helped a number of Christians recover.

Not all of them were spared from death. Most suffered. But their compassionate care helped solidify the community of faith. Christians were not ignorant of the deadliness of the plagues. Yet in Christ they were one body. They were called to build each other up even in the onslaught of suffering.

Moreover, these Christians were able to fulfil this responsibility because they had spiritual resources at hand. They knew they were part of something bigger: the kingdom of God. Theirs was a treasure that could not be infected. And this, in Stark's opinion, made it easier for them to cope in the midst of contagion. He speculates that unity, compassion and belief in life beyond death were factors that contributed to the higher rate of survival experienced by the Christian population. This was a miracle!

The Growth of the Church

But there's more. The way the Christians cared for others also had an impact on the non-Christian population.

Christians tended to the health of many outside their faith, probably people who were their friends and neighbours. Why? Christians had nothing invested in paganism. The Jesus movement was a marginal, even obscure, group in the Roman Empire. But when afflicted pagans were abandoned by their own friends and family, the Christians remained, happy to nurse and comfort the vestige of an empire. They knew they were responsible to love all others as Christ had loved them. Stark believes such care cut the general mortality rate dramatically. And who is to say, he asks sincerely, whether it was the soup or the prayers that brought about recovery? This was a miracle!

Christian nursing impacted pagans in another way. Pagans heard the message of good news as they were cared for. These Christians believed in a God who loved them, an attractive feature that pagan religions didn't have. And pagans came to know God's love was true as they saw with their own eyes how many Christians had been delivered from the plagues. What is more, these Christians had jeopardized and sacrificed their own lives to care for people outside their faith. The plagues would result in mass conversion to Christianity.

These Christians knew they nursed at great risk and at great cost. But they had the courage to do so because their faith story was not ultimately threatened by the present reality of pain, suffering and death. They were witnesses of a different truth. Jesus had taken on the suffering of others and died alongside them. Although his suffering did not put an immediate end to human suffering, his Resurrection offered the promise of a transformed life: a life with no more pain, no more tears, no more death, no more mourning. Christians had been given an opportunity to help make others whole, healing those who suffered and died. These Christians, the converted pagans might have thought, had the power to transform suffering into a gift of God. This was a miracle!

God's Healing Work

What does this mean for us today?

In many cases, modern medicine can relieve what is sometimes called “pointless suffering.” I welcome this wholeheartedly. Suffering in itself is not good. Why would we subject ourselves to the effects of the Antonine or Cyprian plagues when vaccines can prevent such diseases?

Still, medicine cannot eliminate suffering. The source of suffering is deeper than human flesh. Healing is more than relief from physical pain and discomfort. It is the transformation of the whole person. This is the witness of the early Christians. Healing requires courage sustained by faith. I have found my faith sustained, in great part, by the people who have cared for me. Caring does not require expertise, only compassion. It often presents itself in mundane ways. Sometimes the mere gift of presence is enough to show someone they are loved by others and by God.

I started out by saying that I have been given the gift of a second chance. Medicine has not cured me. It has given me time. There is more suffering to endure. Still, in being loved by others, I have found solace. My suffering encourages me to suffer better with others as they suffer. This does not mean I am glad to have cancer. But in a world that does not always understand that suffering can be redeemed, I am convinced that the Christian community can be a healing presence. This kind of healing is the miracle for which I pray.

Dr. Aimee Patterson is a Christian ethics consultant at The Salvation Army Ethics Centre in Winnipeg.

Leave a Comment