The woman sharing her story with me is Karen, an Indigenous woman from the northern region of Manitoba. For the past year, she has been an inmate at the Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge near Maple Creek, Sask., the only healing lodge for women in all of Canada. A high-ranking member of a drug gang in Winnipeg, Karen was arrested and charged with conspiracy to commit trafficking and possession obtained by crime in 2013.

“I was referred here by my parole officer, and I said I would try it out,” says Karen, who has been in and out of prison since she was first arrested on drug-related charges in 2008. “I have no regrets about coming here,” she adds, “it has helped me so much.”

Guided by Indigenous culture and spirituality, Okimaw Ohci provides a unique alternative to a standard federal prison, and its focus on healing impacts every aspect of life there, including its partnership with The Salvation Army.

Open to Heal

Okimaw Ohci is a prison with no bars, located in the Nekaneet Reserve, overlooking a river valley—a cell with a view.

The first thing that struck me when I arrived with Captain Ed Dean, corps officer in Maple Creek, was how little it felt like a prison. No barbed wire. No concrete cell blocks. The facility is a collection of brightly coloured buildings. The women live in apartment-style housing and cook their own food. The guards are known as older sisters and brothers.

Karen is dressed in ordinary clothes with white, beaded moccasins on her feet. A tattoo dedicated to her late husband and six children is one of few hints at the sorrow she has experienced. Though there are guards nearby, we are allowed to talk privately in one of their offices. Indigenous art decorates the room.

As Captain Dean explained as we made the half-hour dirt-road drive from the corps to the facility, the Army's partnership with the healing lodge is unique.

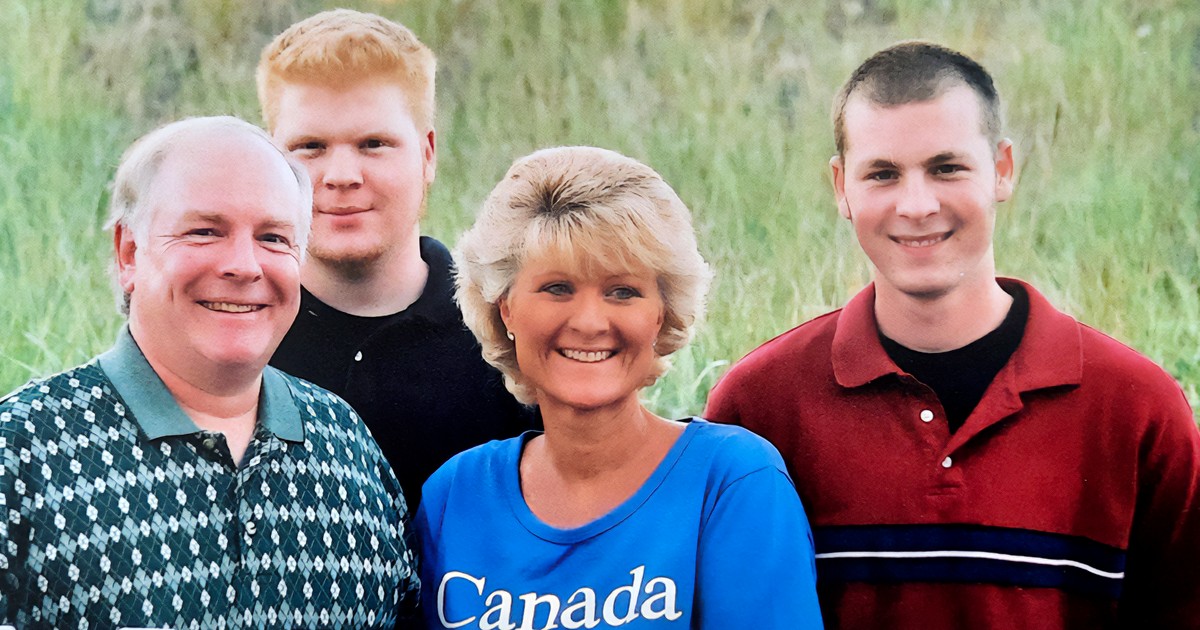

Captain Ed Dean and LeeAnne Skene work together to improve the lives of the women at the healing lodge

Captain Ed Dean and LeeAnne Skene work together to improve the lives of the women at the healing lodge

“When it opened in 1995, they would not permit The Salvation Army or any other church on their ground. Native spirituality was what they were going to teach, and there would be nothing else,” he shares. “We've been working with them for eight years now, and they've come to understand that we're not there to knock what they're teaching—we're not a threat. If anything, we can be a resource for them.”

“The women have to sign a voluntary consent to come to the healing lodge, because they need to be open and willing to heal,” explains LeeAnne Skene, the acting Kikawinaw (“mother”) or executive director. “The Salvation Army walks hand in hand with Correctional Service Canada and the healing lodge on assisting the women in that healing process.”

Building Confidence

Captain Ed Dean and his wife, Captain Charlotte Dean, provide a range of supports to the women at the healing lodge, including community service and work release, a program that gives women who have no work history the opportunity to develop skills, gain work experience and earn money.

As part of community service, women come to the Salvation Army church every Wednesday to assist with the lunch program, helping with preparation, serving and clean-up.

“They're not mandated to do it, but they come in to give back to their community, and that's part of the healing process,” says Captain Ed Dean.

“Oftentimes it's a gradual process for those women to be comfortable enough to openly share with Captain Ed's team,” says Skene. “But once they see that they are accepted as community members, as Salvation Army volunteers, it gives them huge self-confidence. The transformation—it's night and day.”

“The Salvation Army is one of my favourite places to go on community service,” says Angela, who was an inmate at Okimaw Ohci for a year. She was granted parole on the day I visited. “It gives me the feeling of normalness, to be out there in the community and smile and say hi.

“And there's a lot of help there,” she continues. “If you need to talk, tell them your story, you can always tell them the truth. It's homey. As soon as I walk in there it's”—she breathes out—“relax.”

Karen first connected with the Army through community service, volunteering around the corps and at the Army's thrift store in Maple Creek.

“I enjoy working with the clothes—tagging them, putting them out on the floor. I enjoy going through them—like, 'Ooh, look at this!' ” she smiles.

Earning money legally was a first for Karen, who had only known gang life until coming to the healing lodge in her mid-40s.

“I bought my first clothes—legit clothes—with my pay,” she shares. “It feels good to work legit, not looking over my shoulder. Not worrying about cops or a gang member, or that someone high on drugs is going to kill me. So, yeah,” she laughs, “it feels really good to have a legal job.”

“She was so excited when she got her first paycheque,” Captain Dean remembers. “She came to me and said, 'Can I frame it?' ”

A cell block at the Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge

A cell block at the Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge

Spiritual Development

Spiritual life is a key component of the healing process at Okimaw Ohci. The women participate in sharing circles, Indigenous ceremonies and feasts, and learn sacred teachings from their tradition.

“Coming here opened my eyes to my culture,” says Karen. “I am Aboriginal, but I didn't know anything about being Aboriginal. It has helped me find my spirituality, because I was totally gone, lost. All I knew was the gang.”

Karen also attends The Salvation Army once a month, with the help of Captain Dean, who picks her up at the lodge.

“Going to the Army has helped me grow spiritually, big time,” she says. “I found a way, my faith, through them. Being around them, going to the church and singing and praising the Lord—it just came gradually to me.”

For Angela, finding spiritual healing has been a difficult path. Originally from a Cree reserve in central Saskatchewan, she was sent to a residential school at the age of five, along with her four sisters.

“When I was there, I couldn't talk to anybody,” she remembers. “If you were caught talking to a person in Cree, you'd get in trouble. It was lonely—I felt lost and I cried all the time. And I didn't learn anything because I didn't know how to communicate in English.”

Living at the school until she was 13, Angela suffered years of abuse, and was raped and became pregnant at the age of 12.

“Some of those events—I try not to remember them because they are still raw,” she shares. “I don't like my own skin when I think about them, so it's not a comfortable thing to talk about. But I know the more I do it, the better I'll heal and it won't bother me as much. I'll feel better about myself.”

Captain Ed Dean has provided support at the healing lodge for more than eight years

Captain Ed Dean has provided support at the healing lodge for more than eight years

When she first came to the healing lodge in May 2014, Angela was reeling with remorse over the crime she had committed.

“I stabbed my common-law partner, and I had no recollection of doing it because of the alcohol and pills I had in my system,” she shares. “My relationship with my partner was abusive. He hit me, gave me black eyes, for years. Then I started protecting myself and fighting back.

“My lawyer recommended I come here because I had so much healing to do, with the grief and sorrow I had for my late partner, because I loved him, and I still love him today,” she continues. “I didn't mean to do it intentionally. I was just trying to get him off me, so he wouldn't hurt me.”

Angela was convicted of manslaughter, having no history of violence or a criminal record. “When I first came here, I was full of grief and ashamed of myself. I didn't love or respect myself,” she says. “I cried a thousand tears, and it's still not over. This is the beginning—I'm still learning.”

For Angela, a large part of her healing has come through her experiences with both Indigenous spirituality and the church.

“I do both—the ceremonies and church, and I like that. It keeps it balanced,” she says. “They work together, because they're both the same thing for me.”

Above and Beyond

While the chaplaincy, community service and work release are key components of the Army's involvement with the healing lodge, they are only part of its reach in the community.

While we tour the facility with Tara, an inmate, Captain Dean is stopped by two women who thank him for providing turkeys for a recent feast.

The Army also provides gift cards for the women to send to their children at Christmastime.

“Last year, we sent out 67 gift cards,” Captain Dean notes. “But every woman that sent a gift to her children got to sign the card and address the envelope for them.”

Jewelry made by the inmates is sold at The Salvation Army's thrift store

Jewelry made by the inmates is sold at The Salvation Army's thrift store

Not that the Army's relationship with the healing lodge is one-sided. When we pass the lodge's greenhouse on our tour, Captain Dean notes that the inmates grow vegetables for the Army's food bank. The women also make beaded jewelry and moccasins, which are sold in the Army's thrift store. “The proceeds from those crafts benefit the whole population of the facility,” he says.

Captain Dean leaves Tara and me to go to a parole circle, where he is speaking on behalf of an inmate, at her request, and I have an opportunity to speak with some of the lodge's employees.

“Captain Ed goes above and beyond,” one tells me. “He believes in the program, and if he finds out someone is going to be released, he does whatever he can to set them up for success—for example, making sure they have interview clothing, prepping them and setting up resources in the release destination so they have support.”

“Our mission is to contribute to public safety, to integrate the women back into the community to be law-abiding citizens,” explains Skene. “In order for us to do that successfully, we need to be able to provide a continuum of care from the healing lodge to the community. The Salvation Army provides support not only here, but also in multiple other centres where they're able to give the women that connection so they feel like they already have something there when they're released.”

After Karen is released, she plans to become an addictions counsellor and stay involved with The Salvation Army.

“Before I came to the healing lodge, all I knew about the Army was someone standing on a corner at Christmas,” says Karen. “But when I started getting involved, I started to realize how much they help. And that's what I want to do—I want to give back.”

Aboriginals in Corrections

- Aboriginal adults account for nearly one-quarter (24 percent) of admissions to provincial/territorial correctional services, while representing three percent of the Canadian adult population

- Aboriginal women represent 33.6 percent of all federally sentenced women in Canada

- According to the Office of the Correctional Investigator, “The high rate of incarceration for Aboriginal peoples has been linked to systemic discrimination and attitudes based on racial or cultural prejudice, as well as economic and social disadvantage, substance abuse and intergenerational loss, violence and trauma”

- The capacity of the Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge is 48 women

Leave a Comment