The International Headquarters (IHQ) website tells the world that The Salvation Army is “an evangelical part of the universal Christian church.” That has been part of the identity statement since 1994, so it’s not new. But in the past year or so, I’ve wondered whether it’s a label we should be proud to wear.

That’s because “Evangelical” (with a capital E) seems to have taken on a new life and received a lot more attention in the media since the election of U.S. President Donald Trump in 2016. Reliable polls report that more than 80 per cent of white American Evangelicals voted for him. That’s a huge bloc of supporters.

In the United States, “Evangelical” is now treated as a political word. One pastor said, “[Evangelical] is now a tribal, rather than a creedal, description.” He and several other pastors will no longer describe themselves as “Evangelical.” Last year, the campus organization Princeton Evangelical Fellowship—a name it had held since 1937—changed its name to Princeton Christian Fellowship. And we are told that African-American Christians cringe because of the racial overtones of the word “Evangelical.”

It may be different elsewhere in the world. When I chaired the social action commission for the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada (EFC), Brian Stiller, EFC’s president, told me he frequently had to explain to the Toronto Star and other Canadian media that, in Canada, “Evangelical” was not synonymous with the “Christian Right” as it was in the United States. Fast-forward 20 years and Stiller is still explaining to Christianity Today’s readers that “Evangelical” is not a term owned by the United States, and that whatever their internal angst may be, 600 million people elsewhere in the world are happy to own the term as a description of their faith commitments.

Those commitments were identified by David Bebbington in his research of the history of religion in Britain from the 1730s to the 1980s (a period that includes John Wesley, William and Catherine Booth, and John Stott). Bebbington claimed history shows that four features could be used to describe “evangelicals”:

1. A high view of the Bible’s authority;

2. An emphasis on the need for a personal, saving relationship with God;

3. A focus on Jesus’ sacrificial death; and

4. An activist faith that pursues personal sanctification and the improvement of society.

By those criteria, Salvationists should be OK with being called evangelicals. Bebbington’s four features fit.

1. We affirm that if there is a divine rule about faith or life, it will be found only in the Bible; other sources give knowledge but not divine rules.

2. Salvationists place an emphasis on personal faith in Christ. Belief, not a ceremony, makes someone a Christian.

3. From the beginning, The Salvation Army has said that Jesus alone is God-incarnate and that he suffered death in order to free all people from sin.

4. Activism is the Salvationist’s middle name. The heartbeat of the Salvationist is transformed people in a transformed society.

As William Booth put it, “We are a salvation people—this is our speciality—getting saved and keeping saved, and then getting somebody else saved, and then getting saved ourselves more and more until full salvation on earth makes the heaven within, which is finally perfected by the full salvation without, on the other side of the river.”

Despite the fact that The Salvation Army fits Bebbington’s description, I still have a problem embracing the term for myself. Part of that is because I can’t understand how “Evangelicals” could overwhelmingly vote for a man who is proudly not Christlike.

But even if I ignore what’s happening in the United States right now, I rankle at the fact that “evangelical” is often used like a kind of membership card— one that is meant to exclude as much as include. If saying “I’m an evangelical Christian” is a way of looking down my nose—of implying that Catholics and Orthodox and members of the United Church couldn’t be real Christians—I don’t want the adjective. The Apostle Paul said, “Let the one who boasts boast in the Lord” (1 Corinthians 1:31). Any person or denomination that wants to boast about being “evangelical” should take note.

In the end, the question for me—and it’s a big one—is not whether a term can be salvaged, but whether people can discover through us that the gospel really is “good news.” That is, after all, what the Greek word “evangelion” means.

Dr. James Read is the director of The Salvation Army Ethics Centre in Winnipeg.

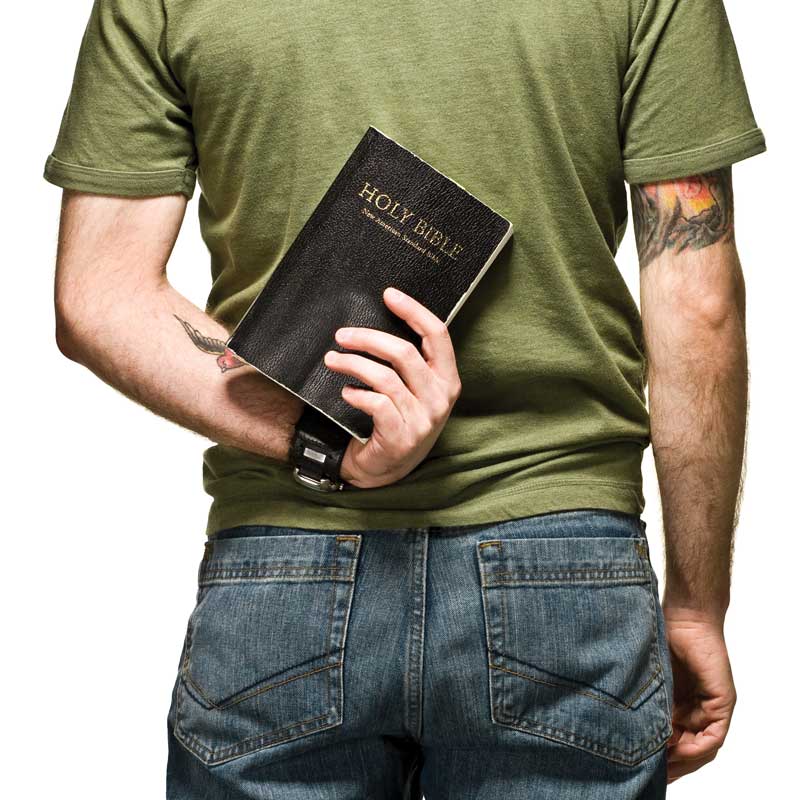

Feature photo: © klosfoto/iStock.com

That’s because “Evangelical” (with a capital E) seems to have taken on a new life and received a lot more attention in the media since the election of U.S. President Donald Trump in 2016. Reliable polls report that more than 80 per cent of white American Evangelicals voted for him. That’s a huge bloc of supporters.

In the United States, “Evangelical” is now treated as a political word. One pastor said, “[Evangelical] is now a tribal, rather than a creedal, description.” He and several other pastors will no longer describe themselves as “Evangelical.” Last year, the campus organization Princeton Evangelical Fellowship—a name it had held since 1937—changed its name to Princeton Christian Fellowship. And we are told that African-American Christians cringe because of the racial overtones of the word “Evangelical.”

It may be different elsewhere in the world. When I chaired the social action commission for the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada (EFC), Brian Stiller, EFC’s president, told me he frequently had to explain to the Toronto Star and other Canadian media that, in Canada, “Evangelical” was not synonymous with the “Christian Right” as it was in the United States. Fast-forward 20 years and Stiller is still explaining to Christianity Today’s readers that “Evangelical” is not a term owned by the United States, and that whatever their internal angst may be, 600 million people elsewhere in the world are happy to own the term as a description of their faith commitments.

Those commitments were identified by David Bebbington in his research of the history of religion in Britain from the 1730s to the 1980s (a period that includes John Wesley, William and Catherine Booth, and John Stott). Bebbington claimed history shows that four features could be used to describe “evangelicals”:

1. A high view of the Bible’s authority;

2. An emphasis on the need for a personal, saving relationship with God;

3. A focus on Jesus’ sacrificial death; and

4. An activist faith that pursues personal sanctification and the improvement of society.

By those criteria, Salvationists should be OK with being called evangelicals. Bebbington’s four features fit.

1. We affirm that if there is a divine rule about faith or life, it will be found only in the Bible; other sources give knowledge but not divine rules.

2. Salvationists place an emphasis on personal faith in Christ. Belief, not a ceremony, makes someone a Christian.

3. From the beginning, The Salvation Army has said that Jesus alone is God-incarnate and that he suffered death in order to free all people from sin.

4. Activism is the Salvationist’s middle name. The heartbeat of the Salvationist is transformed people in a transformed society.

As William Booth put it, “We are a salvation people—this is our speciality—getting saved and keeping saved, and then getting somebody else saved, and then getting saved ourselves more and more until full salvation on earth makes the heaven within, which is finally perfected by the full salvation without, on the other side of the river.”

Despite the fact that The Salvation Army fits Bebbington’s description, I still have a problem embracing the term for myself. Part of that is because I can’t understand how “Evangelicals” could overwhelmingly vote for a man who is proudly not Christlike.

But even if I ignore what’s happening in the United States right now, I rankle at the fact that “evangelical” is often used like a kind of membership card— one that is meant to exclude as much as include. If saying “I’m an evangelical Christian” is a way of looking down my nose—of implying that Catholics and Orthodox and members of the United Church couldn’t be real Christians—I don’t want the adjective. The Apostle Paul said, “Let the one who boasts boast in the Lord” (1 Corinthians 1:31). Any person or denomination that wants to boast about being “evangelical” should take note.

In the end, the question for me—and it’s a big one—is not whether a term can be salvaged, but whether people can discover through us that the gospel really is “good news.” That is, after all, what the Greek word “evangelion” means.

Dr. James Read is the director of The Salvation Army Ethics Centre in Winnipeg.

Feature photo: © klosfoto/iStock.com

Comment

On Monday, December 21, 2020, Bruce Muirhead said:

On Saturday, August 25, 2018, JM said:

On Friday, August 24, 2018, Nnamdi mbaigbo said:

On Thursday, August 23, 2018, Rob DeGeorge said:

But beyond this, Evangelicals, while they did vote for Trump at the tune of 80%, did not really do anything out of the norm. Pew research (a gold caliber research group) shows that Evangelicals over the last several elections have voted for the Republican candidate within a couple of points of 80%. Trump has less to do with this trend as much as the nature of the two party American political system that offers voters essentially two choices to align with all their values. Thus, Evangelicals have had a long history within the American political system asserting their values through less than perfect surrogates. (http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/09/how-the-faithful-voted-a-preliminary-2016-analysis/) (https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300054132/evangelicals-and-politics-antebellum-america )

However, what is more troubling is the sweeping generalization of “Evangelicals” using the term as an elitist exclusionary term when really referring to a specific segment of those who identify as Evangelical. Such gneralizations are unhelpful for dialogue and smacks of the kind of elitism it claims to decry; something Jesus said about a “beam” and a “speck” comes to mind.

The fact is, Evangelicalism in the US has been intertwined with political views for a long time. This definitely needs to change. If one were to poll the average evangelical concerning Bebbington’s marks of evangelicalism, few would get one, let alone all four. Evangelicalism has become a term for too many ideas that mean too many things to too many people. Is it pejorative? For some. But then again, most religious monikers started out as pejoratives: ekklesia, Protestant, Quaker, Methodist… just for a few. Even the term Evangelical started out as a pejorative within the factioned Anglican communion that eventually led to issues between them and Wesley’s Methodists. (http://readingreligion.org/books/wesley-and-anglicans)

If the question is, can “evangelical” be reclaimed, the answer lies somewhere in the reason for why it was lost in the first place. As Salvationists we must recapture the essence of Evangelicalism by lifting up the revelation of Scripture as people of “one book”- as Wesley stated; i.e. all influences and sources are measured through Scripture; by being people who proclaim the transformative power of the Gospel through both the spoken word and the life of faith; by being people who live and lead through a focus on the historical person and work of Jesus Christ that can transform others and the culture in which we live. When we live this out faithfully, unashamedly and intentionally the name Evangelical will restore its place in culture, but I am sure it will be- in this cultural context- no less pejorative.

On Thursday, August 23, 2018, Concerned said:

But I agree with Larry Thorson that Dr Read should not have strayed into political commentary. More often than not I have heard former American presidents quote Scripture or invoke biblical authority, only to act, behave or otherwise legislate that in ways one could equally argue were hardly Christlike. Dr Read is likely right that the behaviour of the current occupant of the White House is not "Christlike", however that is defined. But I would think he would struggle to find any political office holder whose behaviour would be considered "Christlike" when the objective of any politician is to get elected and ( generally) stay elected.

On Thursday, August 23, 2018, Larry Thorson said:

On Thursday, August 23, 2018, jonathan raymond said:

On Wednesday, August 22, 2018, John Stephenson said:

On Tuesday, August 21, 2018, Colleen Winter said:

On Tuesday, August 21, 2018, Major W.J.Kuijpers said:

Leave a Comment