Why do I volunteer at The Salvation Army Lakeshore Community Church’s food pantry in Toronto? I’ve been helping out there for several months, so it’s a good question.

I could trot out the standard responses—volunteer work gives some structure to my week, keeps me feeling useful, provides me some exercise, that sort of thing—and all of them would be partially true.

But the real reason for donating time in the first place was not a very admirable one. I followed my wife, Karen, into volunteerism because I was concerned for her safety, having been told that she worked alone in the church basement with another woman upstairs screening clients—clients who might be dangerous—and I wanted to keep an eye out for trouble.

So I volunteered my time because of prejudice against people I had never seen, and was able to drape my uncharitable assumptions in a cloak of love and loyalty, turning vice into virtue.

My charity, if it can be called that, was a response to fear and guilt.

Magical Thinking

We fear people experiencing poverty and shun them, the people asking for money on the streets, the untreated mental illness screaming its profanities at no one and everyone, the faceless forms sleeping under dirty blankets on downtown sidewalks.

And there’s guilt, knowing that they are maybe just us being forced to play out a losing hand, instead of the handful of aces we hold, and we do not like to think about that very much. We deceive ourselves into thinking that the lives we live would never be like their lives, and that we could pull ourselves out of those degrading conditions if we did have to face them.

But it is magical thinking. We know it is not really true.

Changed Perception

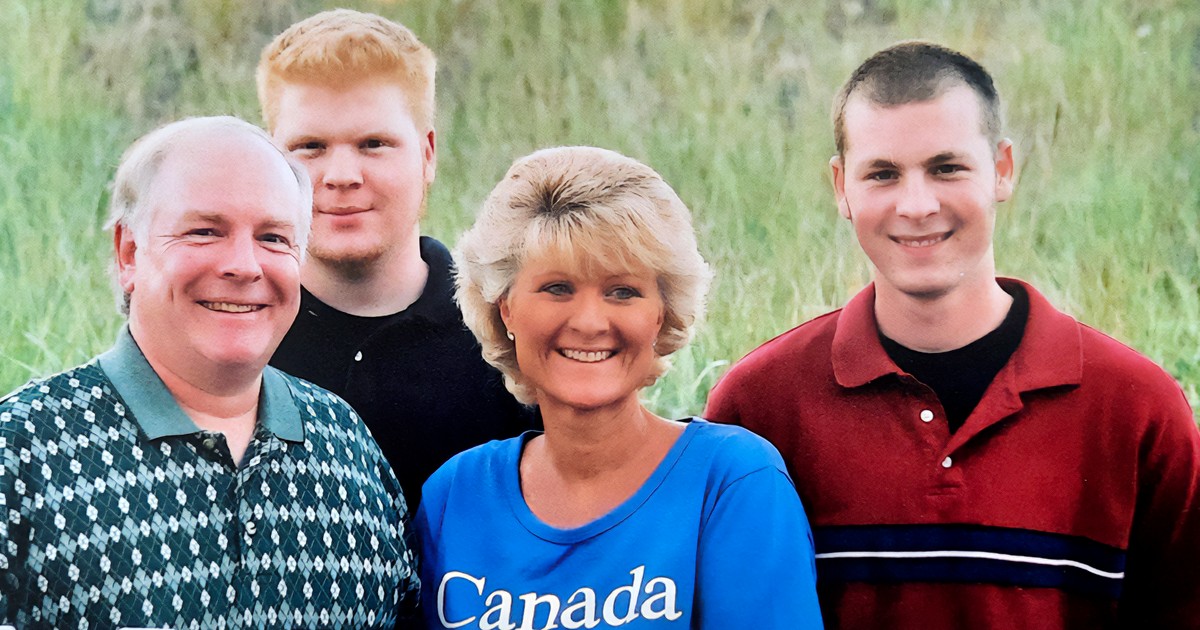

All of us need support. And most of us have supports in some adequate proportion. I have a wife and family. I have a circle of friends. I have my health and a family doctor. I was raised by loving parents. I received a good education, which led me to a good and stable job. I have never been unemployed. I retired in my 50s with a secure pension, mortgage-free.

My supports have helped me avoid and overcome problems. The food pantry helps me to maintain my awareness of this, and to acknowledge that I have some responsibility to try to provide some support to help other people, too.

People experiencing poverty are often an abstraction to most of us who do not associate with them. I seldom spoke to the people I gave money to on the streets, beyond a “You’re welcome” or an absurd “Have a nice day.” I never knew what they felt or what they thought, the circumstances of their misfortune, or anything else about them. In that way, they were not fully human to me.

The food pantry has changed that for me.

They Are Us

At the food pantry, the clients are introduced, and I get to know their names. I watch my wife listen to them talk about their worries: health, unemployment, the rising cost of food and rent, the lack of heat in their apartment or the lack of an apartment at all. People live without a mattress or a pot to heat the soup we supply.

The Salvation Army provides what they can.

We learn of the clients’ likes and dislikes; who has a sweet tooth, who wants to cook nutritious food for themselves and are searching for the ingredients for that cooking, who has a microwave and who does not, who prefers to eat out of cans and who lacks a can opener.

Some clients seem to crave conversation as much as food, and their appointment times can run overtime as a consequence. My wife does not rush them. She understands the importance of her acknowledgment of their obstacles and their distress. They need to tell their stories. They want to connect. They want to explain.

I am proud to watch her work, and humbled at times by the decency of people in need who do not want to take more than their share or to waste what others would use. They are individuals. They are complex. They are happy and angry, sometimes grateful and sad, despairing and hopeful, strong and weak.

These people—as people they have become to me—are likable and dislikable, honest and dishonest, grateful and grasping, in the same proportion of those of us who are not clients.

They are us.

Equitable Exchange

This is, I think, what I meant when I ridiculously told a Salvation Army pastor that the food pantry had “humanized” these people for me. Certainly, they have not become more human just because I got to know something of their personalities and of their circumstances.

If anyone has been humanized by exposure to the food pantry, it’s me. I give of my time, and my character takes what it can in return. I am reminded of our common humanity and of my own good fortune. I work with people whose altruism I admire. I enjoy the thanks of people I have helped to serve.

It has been more than a fair trade, and it is an exchange for which I have become grateful.

This story is from:

Leave a Comment