Imagine being able to cure cancer, prevent disease, improve crops and even eradicate mosquitoes. It might sound like science fiction, but it’s quickly becoming science fact. Researchers are on the verge of a new era in molecular biology, with the power to silence or activate specific genes using something called CRISPR.

CRISPR is an acronym for “Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats,” but the name isn’t as important as knowing how it works. CRISPR is part of a microbial immune system—a stretch of DNA that is able to recognize and destroy invading viruses. Scientists have been able to adapt this system to target and modify the genes of plants and animals, including human beings.

Think of it like the “cut and paste” function on your computer. Like editing a sentence in a document, CRISPR can cut out an undesirable strand of DNA so it can be replaced with a desirable strand. In 2015, a baby with leukemia was treated with genetically edited white blood cells. At the time of this writing, she is alive and in remission.

In the future, CRISPR could also be used to edit reproductive cells, making changes that are passed on to offspring. For example, preventing the development of Huntington’s disease in one embryo would mean preventing it in future generations.

We aren’t there yet. Even the most prized gene editing technology, CRISPRCas9, has a lot of kinks to work out. But many in the scientific community view this not as an impediment, but as a matter of time. One of the scientists who discovered CRISPR-Cas9, Jennifer Doudna, says: “The possibilities are limited only by our collective imagination.”

Imagination is a great thing—you might say it’s in our DNA. But it must be tempered by ethics.

Take my CRISPR metaphor. Most of the time, I think of editing in a positive way. When I edit a document, I am removing typos, restructuring awkward sentences and reversing the order of paragraphs to create an improved second draft. I can also review the second draft, and if I don’t like a change I can undo it. Unfortunately, I’ve also been in the position of editing, then saving and closing the document. The edit has become permanent. This is what gene editing potentially offers—a second draft of humanity.

In 2015, the International Summit on Human Gene Editing released a report that focused on the risks of editing reproductive cells, including changing the human gene pool. In my view, the report overlooks the “unlimited possibilities” that can come with altering the genes of individual people.

But more to the point, the report raised two ethical questions that must be considered. First, we must resolve safety risks. Second, we need a “broad societal consensus” among global stakeholders regarding both the appropriateness of this therapy and the acceptable norms for its use. The list of who counts as a stakeholder is fairly lengthy. In addition to the usual suspects—scientists, research funders and policy-makers—it names ethicists, health-care providers, patients and faith leaders.

Christian denominational or ecumenical bodies may be skeptical about how their comments will be received. But Christians are not called to be silent on serious moral issues, especially when the wind is blowing against us.

So, beyond speaking to matters of safety, what can Christian leaders contribute? Before jumping ahead to possible outcomes, like designer babies or bionic humans, perhaps we should pay attention to more basic, immediate matters. Even a slight step across the threshold from medical therapy to technological enhancement should raise ethical questions.

For instance, what do Christians say about what is good about—or for—human beings? What does being created in God’s image have to do with human creativity and imagination? What does it have to do with human imperfection?

I’m convinced that if Christian leaders begin with general theological questions like these, we will be better prepared to engage in conversations on the practical ethics of gene editing technologies. And I wouldn’t be surprised if some Christian ethical conclusions are shared outside our faith community.

Dr. Aimee Patterson is a Christian ethics consultant at The Salvation Army Ethics Centre in Winnipeg.

Feature photo: © Natali_Mis/iStock.com

Forging Ahead

How partnerships in Canada and Bermuda are strengthening the international Salvation Army.

by Major Heather Matondo FeaturesInternational DevelopmentAdvancing the mission of the international Salvation Army through partnerships in Canada and Bermuda.

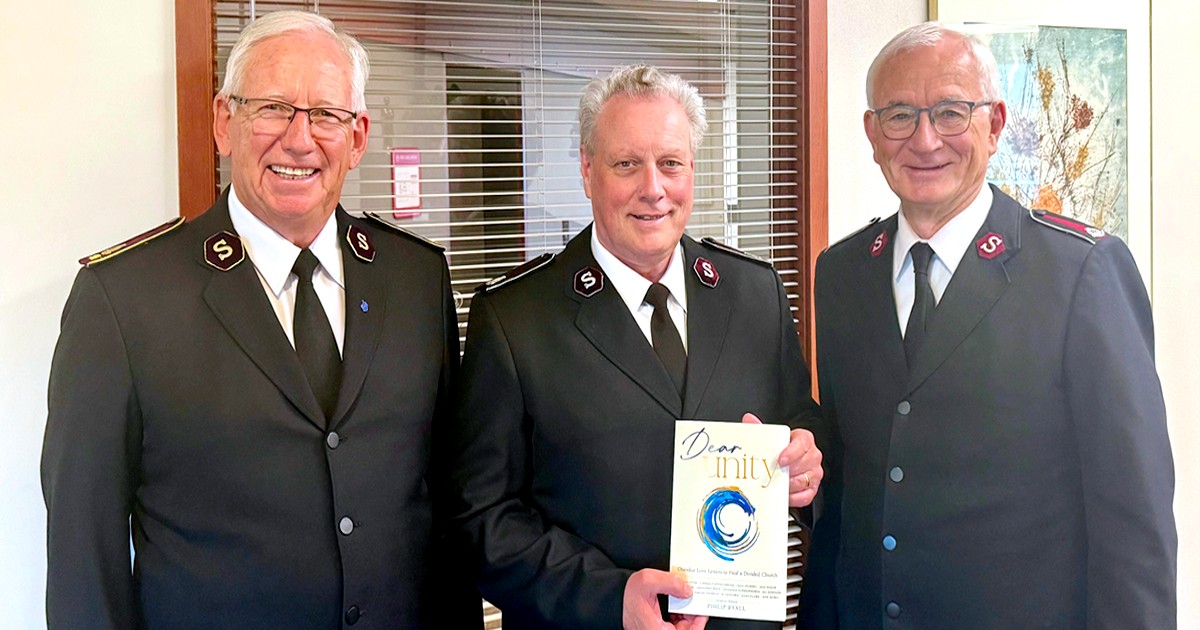

That They May All Be One

A love letter from The Salvation Army to the broader church.

by General Brian Peddle (Rtd) Opinion & Critical Thought"Dear Unity: Overdue Love Letters to Heal a Divided Church" contains 30 chapters, one written by General Peddle, from a variety of denominations and traditions, expressing a desire for unity among churches.

The Salvation Army is active in more than 130 countries worldwide. With such a wide scope of ministry, there are many service opportunities for both officers and lay personnel interested in serving overseas. Below is a list of available positions in other Salvation Army territories, prepared by the IHQ personnel department.

Read More

Leave a Comment