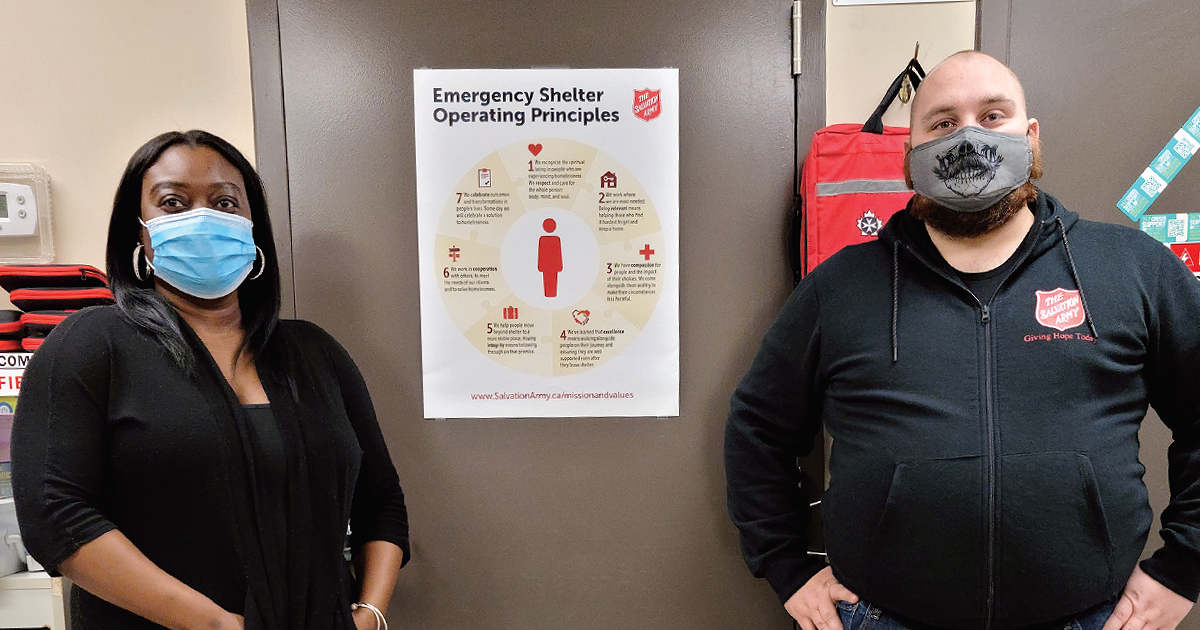

(Above) Tanisha Bryan and Paul Puhringer lead the P.A.C.E. (peers aiding in critical experiences) team for Peel Shelter and Housing Services

In 2016, Canada was in the middle of a growing opioid crisis, with fentanyl—a synthetic pain medication 100 times more powerful than morphine—fuelling an explosion of overdoses and deaths.

In 2016, Canada was in the middle of a growing opioid crisis, with fentanyl—a synthetic pain medication 100 times more powerful than morphine—fuelling an explosion of overdoses and deaths.

“There was a four-month period, from June to September, when we lost a lot of our clients—guys that we knew well,” says Paul Puhringer, a front-line worker at The Salvation Army’s Wilkinson Road Shelter, in Brampton, Ont. “Fentanyl came in, and it just started downing them real fast. We were trained to administer naloxone and we’d be running to help several times a week.”

“It was a scary time,” agrees Tanisha Bryan, an outreach housing support worker at the Army’s Honeychurch Family Life Resource Centre in Brampton. “It was just overdose after overdose after overdose.”

When anyone encounters the threat of serious injury or death, it’s a traumatic experience that can evoke feelings of fear and helplessness, undermine a person’s sense of safety and security, and interfere with their ability to function. Acute stress, if left untreated, can lead to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“We realized we needed to be here for each other as staff,” says Bryan. “So we came together as a team, with employees from the various Salvation Army shelters in Peel Region, to offer support during and after critical incidents.”

The P.A.C.E. (peers aiding in critical experiences) team, launched in June 2019 and led by Puhringer and Bryan, is modelled on a method for helping first responders called critical incident stress management (CISM). Durham Regional Police, which has successfully used this method with their force, provided training in group and individual crisis intervention.

Although the overdose epidemic was the catalyst for forming the P.A.C.E. team, shelter workers are exposed to other distressing experiences.

“The type of critical incident depends on the type of shelter,” says Bryan. “For Paul, it could be an overdose. In my work at an emergency shelter for abused women and children, it could be helping a woman with her injuries, or a situation where a child is removed from a family.

“It’s heavy work that we do. It causes a lot of burnout in our peers.”

Over the past year, the COVID-19 pandemic has only added to the weight, with increased safety measures, worries over the possibility of outbreak and wary landlords making it difficult to find housing. Another consequence has been an increase in domestic violence, as families contend with stress over job loss and spend more time together.

“There’s a lot of pressure on people,” says Bryan. “We’re dealing with our own fears, plus the fears of our clients, but we have to be the calm, reassuring ones. We still have a service to provide—we have to make sure we’re the best we can be when we’re at work.”

After a critical incident, the team is called to provide one-on-one, confidential support, following the S.A.F.E.R. model— a form of psychological first aid.

“It’s about creating a safe space,” says Bryan. “We stabilize the situation, acknowledge the crisis, facilitate understanding, encourage effective coping and refer to external resources, such as our employee assistance program. We’re not there to fix someone—we’re there for support.”

Captains Robert and Laura Burrell, chaplains at Peel Shelter and Housing Services, are also part of the P.A.C.E. team and offer spiritual care when requested.

After the initial meeting, the team always follows up to let the individual know they aren’t alone and help is available.

The message is getting out. From June 2019 to June 2020, the P.A.C.E. team made more than 1,000 contacts, most often related to work stress.

“The number of calls shows that our peers think we are trustworthy, that they can depend on us,” says Bryan. “They can come to us and share whatever it is that they’re feeling, and we can help.”

That’s why Puhringer first joined the team.

“Dealing with overdoses and other work stressors affected me, but I didn’t want to go and talk to a stranger,” he says. “It’s more comfortable to open up to a peer, someone you know.”

This story is from:

“It was a scary time,” agrees Tanisha Bryan, an outreach housing support worker at the Army’s Honeychurch Family Life Resource Centre in Brampton. “It was just overdose after overdose after overdose.”

When anyone encounters the threat of serious injury or death, it’s a traumatic experience that can evoke feelings of fear and helplessness, undermine a person’s sense of safety and security, and interfere with their ability to function. Acute stress, if left untreated, can lead to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“We realized we needed to be here for each other as staff,” says Bryan. “So we came together as a team, with employees from the various Salvation Army shelters in Peel Region, to offer support during and after critical incidents.”

The P.A.C.E. (peers aiding in critical experiences) team, launched in June 2019 and led by Puhringer and Bryan, is modelled on a method for helping first responders called critical incident stress management (CISM). Durham Regional Police, which has successfully used this method with their force, provided training in group and individual crisis intervention.

Although the overdose epidemic was the catalyst for forming the P.A.C.E. team, shelter workers are exposed to other distressing experiences.

“The type of critical incident depends on the type of shelter,” says Bryan. “For Paul, it could be an overdose. In my work at an emergency shelter for abused women and children, it could be helping a woman with her injuries, or a situation where a child is removed from a family.

“It’s heavy work that we do. It causes a lot of burnout in our peers.”

Over the past year, the COVID-19 pandemic has only added to the weight, with increased safety measures, worries over the possibility of outbreak and wary landlords making it difficult to find housing. Another consequence has been an increase in domestic violence, as families contend with stress over job loss and spend more time together.

“There’s a lot of pressure on people,” says Bryan. “We’re dealing with our own fears, plus the fears of our clients, but we have to be the calm, reassuring ones. We still have a service to provide—we have to make sure we’re the best we can be when we’re at work.”

After a critical incident, the team is called to provide one-on-one, confidential support, following the S.A.F.E.R. model— a form of psychological first aid.

“It’s about creating a safe space,” says Bryan. “We stabilize the situation, acknowledge the crisis, facilitate understanding, encourage effective coping and refer to external resources, such as our employee assistance program. We’re not there to fix someone—we’re there for support.”

Captains Robert and Laura Burrell, chaplains at Peel Shelter and Housing Services, are also part of the P.A.C.E. team and offer spiritual care when requested.

After the initial meeting, the team always follows up to let the individual know they aren’t alone and help is available.

The message is getting out. From June 2019 to June 2020, the P.A.C.E. team made more than 1,000 contacts, most often related to work stress.

“The number of calls shows that our peers think we are trustworthy, that they can depend on us,” says Bryan. “They can come to us and share whatever it is that they’re feeling, and we can help.”

That’s why Puhringer first joined the team.

“Dealing with overdoses and other work stressors affected me, but I didn’t want to go and talk to a stranger,” he says. “It’s more comfortable to open up to a peer, someone you know.”

Leave a Comment