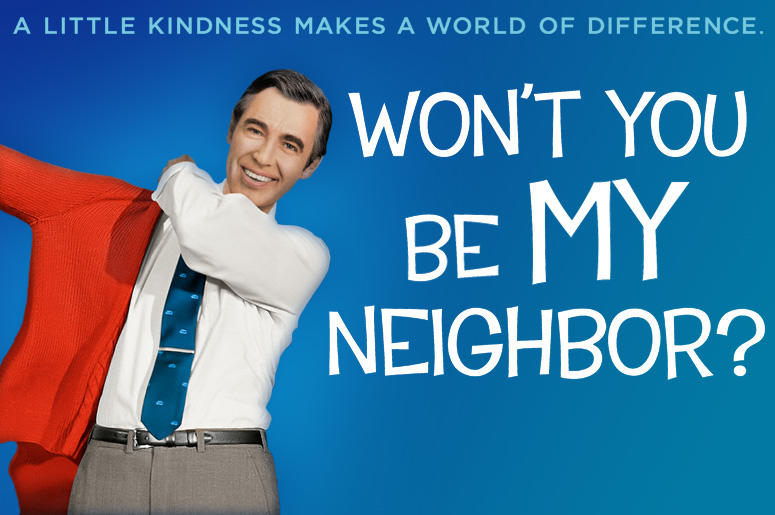

North Americans seem to love sharing myths about Fred Rogers, the friendly neighbour known the world over as Mister Rogers. Consider the one about how he wore cardigans to cover up his tattoos (false). Or the one about how he was an ordained minister. That one is true—he graduated from Pittsburgh Theological Seminary in 1963—and it’s far more foundational to Rogers’ legacy than you might think.

As They Are

Rogers was a man defined by his Christian faith, and the message that he taught every day on his beloved children’s show was shaped by it. “If Protestants had saints,” Jonathan Merritt wrote in The Atlantic, “Mister Rogers might already have been canonized.”

The news that Tom Hanks was portraying Fred Rogers in a biopic was met with frenzied glee, as Hanks is one of the few contemporary celebrities who approaches Rogers’ universally beloved status. But even Hanks, for all his charms, doesn’t occupy the same stratosphere of Rogers’ legacy of moral and spiritual importance.

He was a pastor on television in the golden era of televangelism, but unlike televangelists, Rogers’ focus wasn’t on eternal life, but our own interior lives. Christian evangelists were making a name for themselves preaching about the wickedness of mankind, but Rogers was more interested in his viewers’ inherent value and worth. Evangelists were finding ways the human race didn’t measure up to God’s moral standard. But Rogers said over and over again: “You’ve made this day a special day by just your being you. There is no person in the whole world like you, and I like you just the way you are.”

If this sounds like the sort of shallow talking point espoused by the likes of American televangelist Joel Osteen, consider these words: “Love isn’t a perfect state of caring,” Rogers wrote in The World According to Mister Rogers. “It’s an active noun like ‘struggle.’ To love someone is to strive to accept that person exactly the way he or she is, right here and now.” Rogers wasn’t telling children that they were so perfect that there was no room for them ever to improve as people; just that he loved them as they were, regardless of who they were or what they had done.

Hi, Neighbour!

“I think everybody longs to be loved, and longs to know that he or she is lovable,” Rogers said in the 2003 documentary America’s Favorite Neighbor. “And, consequently, the greatest thing that we can do is to help somebody know that they’re loved and capable of loving.”

Rogers echoed the sentiment of the biblical passage 1 John 4:10, “This is love: not that we loved God, but that He loved us and sent His Son as an atoning sacrifice for our sins.” The focus is not just how important it is that you’re loved, but also how vital it is to be loving.

Rogers’ theological messages could be traced to the biblical notion of “neighbour” and Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan (see Luke 10:25-37), where a Jewish man was mugged and left for dead, his body ignored by the religious elite who passed by. But then a man from the despised country of Samaria stopped and showed kindness. This was Jesus’ roundabout way of answering the question “Who is my neighbour?”

Jesus’ point—that the Samaritan and the Jewish man were neighbours in a spiritual sense, if not a physical one—feels right at home on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, where Rogers greeted you with a daily “Hi, neighbour!” as if the whole world lived in the same close-knit community.

As They Are

It might be tempting to think Mister Rogers’ message came from a simpler time, but his show debuted just a few months after the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the world remained on tenterhooks. Rogers’ message upended a few apple carts in his own time, and it frankly remains countercultural today.

The notion of a worldwide neighbourhood in which everyone belongs has been replaced by a call for isolationism. Rogers was aware of our own propensity to kick people out—an early episode of his show featured King Friday, the ruler of the Neighborhood of Make-Believe, attempting to build a wall around his kingdom to protect it from change. Sound familiar?

A Necessary Theology

Perhaps the gentle, accepting theology of Rogers is all well and good for children, but adults do not have the luxury of unconditional love and acceptance. You can feel this sentiment in Family Research Council President Tony Perkins’ recent Politico interview, where he hedged Jesus’ language about turning the other cheek. “You know, you only have two cheeks,” he said. “Christianity is not all about being a welcome mat which people can just stomp their feet on.” Jesus’ teaching is a nice idea, Perkins seems to be saying. But it’s just not realistic.

Rogers thought of the act of loving and accepting someone as your neighbour as holy business, as he said in a 2001 commencement address at Middlebury College: “When we look for what’s best in the person we happen to be with at the moment, we’re doing what God does; so in appreciating our neighbour, we’re participating in something truly sacred.”

It may sound old-fashioned, but Mister Rogers’ theology was radical in 1962 when his show debuted, and it remains radical today. That’s why it resonated. That’s why it’s still necessary.

Reprinted from The Washington Post, January 30, 2018

As They Are

Rogers was a man defined by his Christian faith, and the message that he taught every day on his beloved children’s show was shaped by it. “If Protestants had saints,” Jonathan Merritt wrote in The Atlantic, “Mister Rogers might already have been canonized.”

The news that Tom Hanks was portraying Fred Rogers in a biopic was met with frenzied glee, as Hanks is one of the few contemporary celebrities who approaches Rogers’ universally beloved status. But even Hanks, for all his charms, doesn’t occupy the same stratosphere of Rogers’ legacy of moral and spiritual importance.

He was a pastor on television in the golden era of televangelism, but unlike televangelists, Rogers’ focus wasn’t on eternal life, but our own interior lives. Christian evangelists were making a name for themselves preaching about the wickedness of mankind, but Rogers was more interested in his viewers’ inherent value and worth. Evangelists were finding ways the human race didn’t measure up to God’s moral standard. But Rogers said over and over again: “You’ve made this day a special day by just your being you. There is no person in the whole world like you, and I like you just the way you are.”

If this sounds like the sort of shallow talking point espoused by the likes of American televangelist Joel Osteen, consider these words: “Love isn’t a perfect state of caring,” Rogers wrote in The World According to Mister Rogers. “It’s an active noun like ‘struggle.’ To love someone is to strive to accept that person exactly the way he or she is, right here and now.” Rogers wasn’t telling children that they were so perfect that there was no room for them ever to improve as people; just that he loved them as they were, regardless of who they were or what they had done.

Hi, Neighbour!

“I think everybody longs to be loved, and longs to know that he or she is lovable,” Rogers said in the 2003 documentary America’s Favorite Neighbor. “And, consequently, the greatest thing that we can do is to help somebody know that they’re loved and capable of loving.”

Rogers echoed the sentiment of the biblical passage 1 John 4:10, “This is love: not that we loved God, but that He loved us and sent His Son as an atoning sacrifice for our sins.” The focus is not just how important it is that you’re loved, but also how vital it is to be loving.

Rogers’ theological messages could be traced to the biblical notion of “neighbour” and Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan (see Luke 10:25-37), where a Jewish man was mugged and left for dead, his body ignored by the religious elite who passed by. But then a man from the despised country of Samaria stopped and showed kindness. This was Jesus’ roundabout way of answering the question “Who is my neighbour?”

Jesus’ point—that the Samaritan and the Jewish man were neighbours in a spiritual sense, if not a physical one—feels right at home on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, where Rogers greeted you with a daily “Hi, neighbour!” as if the whole world lived in the same close-knit community.

As They Are

It might be tempting to think Mister Rogers’ message came from a simpler time, but his show debuted just a few months after the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the world remained on tenterhooks. Rogers’ message upended a few apple carts in his own time, and it frankly remains countercultural today.

The notion of a worldwide neighbourhood in which everyone belongs has been replaced by a call for isolationism. Rogers was aware of our own propensity to kick people out—an early episode of his show featured King Friday, the ruler of the Neighborhood of Make-Believe, attempting to build a wall around his kingdom to protect it from change. Sound familiar?

A Necessary Theology

Perhaps the gentle, accepting theology of Rogers is all well and good for children, but adults do not have the luxury of unconditional love and acceptance. You can feel this sentiment in Family Research Council President Tony Perkins’ recent Politico interview, where he hedged Jesus’ language about turning the other cheek. “You know, you only have two cheeks,” he said. “Christianity is not all about being a welcome mat which people can just stomp their feet on.” Jesus’ teaching is a nice idea, Perkins seems to be saying. But it’s just not realistic.

Rogers thought of the act of loving and accepting someone as your neighbour as holy business, as he said in a 2001 commencement address at Middlebury College: “When we look for what’s best in the person we happen to be with at the moment, we’re doing what God does; so in appreciating our neighbour, we’re participating in something truly sacred.”

It may sound old-fashioned, but Mister Rogers’ theology was radical in 1962 when his show debuted, and it remains radical today. That’s why it resonated. That’s why it’s still necessary.

Reprinted from The Washington Post, January 30, 2018

Leave a Comment