What a week! It began on Palm Sunday, with a celebratory procession entering Jerusalem with shouts of “Hosanna!” Jesus was ushered into the holy city as a conquering hero, with the crowds proclaiming his imminent accession to the throne of David. It ended on Friday, with his agonized cry, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34), as Jesus gave up his last breath after the brutal sadism of his Crucifixion. In between, the cries of “Hosanna!” became shouts of “Crucify him! Crucify him!”

On the surface, the transformation of the crowd’s mood from ecstatic expectation on Sunday to ravenous bloodthirst a few days later may seem hard to explain. But it makes sense in the larger telling of Jesus’ story in the Gospel of Mark. According to Mark, one of the major challenges that Jesus faced was overturning the expectations that the people—including his own disciples— had for their Messiah. They expected the Messiah to be a new David, a conquering hero who would overthrow the oppressive Roman rule and establish, at last, God’s reign of righteousness, with Jesus, a son of David, on the throne in Jerusalem. The ensuing days would be glorious, a time of unprecedented prosperity and supremacy for the Jewish kingdom, as well as a time of power and influence for Jesus’ closest followers. But that, however, was not the mission of the Messiah, as Jesus was to teach. It is this clash of expectations that prompted the stark transformation from shouts of “Hosanna!” to “Crucify him!”

You Are the Messiah

To understand this, we need to go back to the scene in which Jesus quizzed his disciples about the public’s perception of him (see Mark 8:27-30). Some in the crowd thought Jesus was a prophet, perhaps the great Elijah or a reappearing John the Baptist. They recognized Jesus’ closeness to God, that he was a messenger from God. Quickly, Jesus turned the question to his disciples. “Who do you say that I am?” Peter, speaking on behalf of all the disciples, exclaimed, “You are the Messiah!” Inexplicably, Jesus ordered the disciples to guard this as a secret.

But even more shockingly, Jesus then proceeded to teach the disciples that he must suffer, be rejected by the leadership of the Jewish people, be killed and then rise again. Peter, in his characteristically impetuous manner, objected to this. Jesus’ prediction of his suffering, death and Resurrection did not fit with Peter’s own understanding of what it meant to proclaim Jesus as the Messiah. For Peter and the disciples, Jesus’ messiahship must lead to triumph over the Romans, to Jesus’ enthronement on the throne of King David, and—for them—prominent positions in his kingdom. That was their expectation. The allure of following Jesus, then, was the prospect of sharing in the power and glory of the conquering Messiah. But what Jesus promised instead was suffering, rejection and a cross. It’s little wonder that Peter objected to this.

In the following verses (see Mark 8:34-9:1), Jesus taught his disciples that following him required self-denial, taking up one’s cross and losing one’s life. Peter had stumbled upon the truth about Jesus—that he was the Messiah—but it was only a half-truth. Peter and the other disciples were partially blinded by their own expectations and ambitions. They could not hear what Jesus was teaching them; they could not understand his mission. They had eyes and ears but could neither see nor hear what he said.

The blindness of the disciples continues in the next chapter. Beginning in Mark 9:30, Jesus revealed to the disciples for the second time that he would be betrayed, killed and rise again. But, once again, the disciples did not understand what Jesus was saying about his messianic mission. This is confirmed in the following verses as the disciples argued among themselves about who was the greatest (see Mark 9:33-34). Such a question was possible only because the disciples were mired in their expectation that Jesus’ messiahship would lead to conquest and power. This was such a powerful and attractive prospect that it drowned out the teaching of Jesus and blinded the disciples to the reality of his messianic mission.

In response to the disciples’ obsession with greatness and power, Jesus turned everything on its head. “Anyone who wants to be first must be the very last, and the servant of all” (Mark 9:35). To the disciples—and I suspect to many Christians today—this must have sounded like nonsense.

The Suffering Servant

As Jesus and the disciples continued their journey toward Jerusalem, Jesus made a third and final attempt to prepare his closest followers for the nature of his messiahship and, in turn, for their discipleship. Beginning in Mark 10:33, Jesus once again predicted his suffering, death and Resurrection—this time in greater detail. Immediately after, James and John made a shocking request of Jesus: grant us to sit on your right and left hand in your kingdom. They were still seeking power and glory; they were still imagining that Jesus’ messiahship would be evident in dominion and triumph. What that meant for James and John was the possibility of holding positions of power in Jesus’ kingdom. The other 10 disciples were no more tuned in to what Jesus was saying, since they were angry that James and John had attempted to gain an inside track on them. Jesus, perhaps with some frustration, continued his teaching, asserting that while rulers of the Gentiles may lord it over their subjects, among the followers of Jesus, such assertions of power over one another are out of bounds. Greatness, when following a suffering Messiah, is found not in glory but in service; discipleship is evident in humility rather than an arrogant quest for power. Suffering and service, more than power and glory, are the marks of Jesus’ followers.

The Messianic Secret

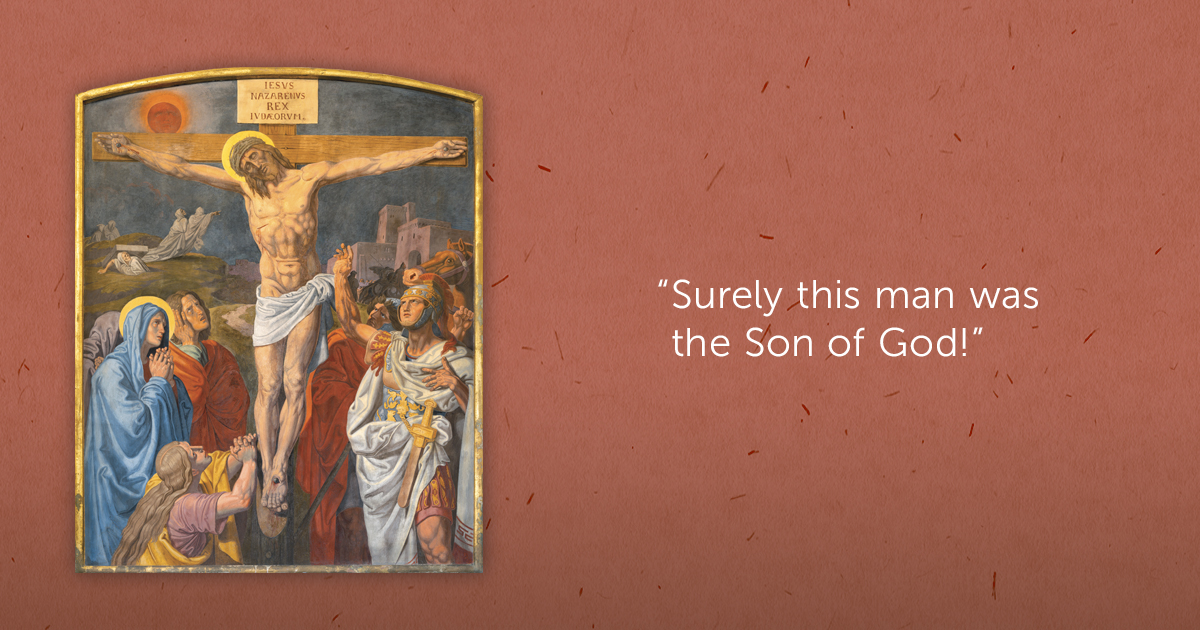

If even Jesus’ closest disciples were so blind to the true nature of his messiahship and its implications for those who would be his followers, is it any wonder that throughout Mark’s Gospel, Jesus commands silence about his messianic mission? It’s a great secret; a messianic secret. Demons who recognize Jesus are commanded to silence (see Mark 1:34; 3:11-12); recipients of healing are told to tell no one what they know about Jesus (see Mark 7:36). And in Mark, Jesus always refers to himself as “Son of Man” and never as “Christ” or “Son of God.” In fact, there is only one human character who is permitted to proclaim the identity of Jesus. It was not one of Jesus’ disciples, who had spent countless hours observing his life and receiving his instruction; it was not one of the people whom Jesus had healed; and it certainly was not one of the demons who recognized Jesus. No, the only character in Mark who is permitted to speak the true identity of Jesus is a hated Roman centurion who, having seen Jesus suffer through his Crucifixion and death, proclaimed, “Surely this man was the Son of God!” (Mark 15:39).

What the disciples had failed to recognize through Jesus’ three Passion predictions, this hated Roman soldier saw most clearly in the shadow of the cross: Jesus’ messiahship overthrows human ambitions for power and glory. It goes against the grain of human self-interest and sinfulness to forge a different path. Discipleship to a crucified Messiah leads to a striking contrast in relationships, in the world and in the community of Jesus’ followers—or at least it should. Lording over one another, in all its forms, is rendered out of order in the shadow of the cross. There is no legitimate hierarchy among the disciples of the crucified Messiah.

The Way of the Cross

Temptations to pursue glory, authority and the perks of power abound even among the followers of Jesus to this day. Sometimes, even among those of us who profess to take the Bible seriously and to be disciples of Jesus, the pursuit of such “greatness” continues unabated. It shows up in claims to authority over others. But Jesus’ messiahship exposes such claims as fraudulent. Even a Roman centurion could see what Jesus’ closest disciples could not. When the cross becomes the lens through which we see the nature of discipleship to Jesus, everything changes. Serving, rather than being served, becomes the way of the disciple.

It’s no surprise that we sometimes succumb to the allure of shouting hosannas in glorious processions instead of taking the way of the cross. Rushing past Calvary to get to the empty tomb is understandable; it feeds our tendency to pursue the adoring crowd. But as Mark teaches us, to do so leads to a distorted discipleship that focuses on the trappings of success and elevates us above others. Jesus, on the other hand, through his suffering and death, taught us that our practice of discipleship—just like the disciples’—may need to be transformed in the shadow of the cross.

Dr. Donald E. Burke is a professor of biblical studies at Booth University College in Winnipeg.

Photo: The fresco of Crucifixion as part of Cross way station in the church of St. John the Nepomuk by Josef Furlich (1844-1846)/Renáta Sedmáková via stock.Adobe.com

This story is from:

Leave a Comment