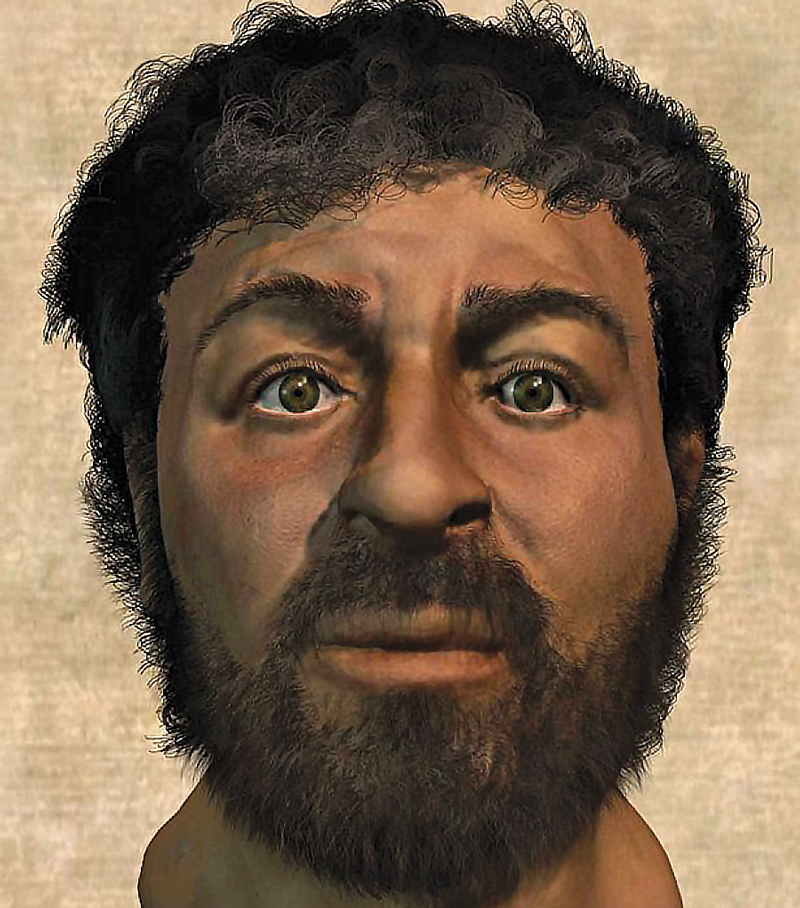

Picture Jesus in your mind. What does he look like? Is he fat, thin or in between? Is he frowning? Smiling? Crying? Does he have long or short hair? Is his beard close-cropped or bushy? Now tell me, does he have light-brown or blond hair, blue eyes and pale skin? That was the image of Jesus I’d seen for most of my life. From Sunday school illustrations, to paintings in church foyers, to actors portraying Jesus in films, Jesus was always a handsome and white—or, at best, slightly tanned—man. This version of Jesus, however, does not match reality.

Isaiah 53:2, believed by many Christians to be a prophecy about the Messiah, states: “He had no beauty or majesty to attract us to him, nothing in his appearance that we should desire him.” This is echoed throughout the New Testament. Although Jesus’ appearance is never spelled out in vivid detail, his ability to blend into crowds would lead us to believe that he looked like a typical man of his day. As a Middle Eastern man who walked in the sun from village to village, he probably had dark brown skin. The Jesus we see in murals and paintings, white-skinned with flowing hair that would put any shampoo commercial to shame, is not the truth.

So why do we show him this way? In most, but not all, places in the world, Christianity spread with colonization. In North America, influenced by Europe, that has meant representing Jesus through a predominantly white cultural and historical lens. By doing so, however, we chip away at the important human side of Christ.

It is a tenet of our faith that Jesus was fully God and fully man. Most of us have the God part figured out—we pray to him all the time—but Jesus as a man is harder to wrap our heads around. When his friend Lazarus died, he cried. When he saw the moneychangers in the temple, he got angry. When he wandered in the desert, he was hungry.

Like us, Jesus saw the world, felt the ground beneath his feet, heard the birds sing, smelled the spices in the market and tasted food. Jesus was born in a particular time and place, within a particular ethnicity. This is the mystery and beauty of the Incarnation. He was the Word made flesh, and the flesh he chose was a Middle Eastern Jewish man. To deny Jesus his humanity is, in effect, to deny Christ himself. Unless we are willing to love Jesus as a brown-skinned Jewish man, can we really say we love him?

This is not a call to haul every blond-haired, blue-eyed portrait of Jesus to the dump. Some people take comfort in these paintings. I have seen images of Black Jesus in Kenya and Asian Jesus in South Korea, and they show us that he belongs to every culture. We must be careful, though, not to worship our own image. That is the textbook definition of idolatry.

I must confess, however, that while I have no problem with Asian or Black Jesus (in fact, I have a Kenyan artist’s portrayal of the Last Supper hanging in my dining room), I find Caucasian Jesus problematic because of the historical baggage associated with colonization. European features were considered beautiful and people of colour were treated as inferior.

Sadly, these messages continue to influence how many people of colour see themselves, in addition to perpetuating racism, which hurts society as a whole. It’s important to combat old colonial notions of what Christ looked like, to open the door further for those who aren’t white-skinned and blue-eyed. Portraying Jesus as Caucasian reinforces colonialism and can make him a symbol of oppression.

If the only way you can serve Jesus is by seeing him as white-skinned, I suggest that your faith is not in God, but in the power that comes with cultural Christianity. Portraying Jesus as he actually looked may help break down explicit and implicit walls of racism in the global church, and work toward a true fellowship of all believers. After all, we all serve a Middle Eastern Saviour.

Darryn Oldford is a senior soldier in Toronto.

Isaiah 53:2, believed by many Christians to be a prophecy about the Messiah, states: “He had no beauty or majesty to attract us to him, nothing in his appearance that we should desire him.” This is echoed throughout the New Testament. Although Jesus’ appearance is never spelled out in vivid detail, his ability to blend into crowds would lead us to believe that he looked like a typical man of his day. As a Middle Eastern man who walked in the sun from village to village, he probably had dark brown skin. The Jesus we see in murals and paintings, white-skinned with flowing hair that would put any shampoo commercial to shame, is not the truth.

So why do we show him this way? In most, but not all, places in the world, Christianity spread with colonization. In North America, influenced by Europe, that has meant representing Jesus through a predominantly white cultural and historical lens. By doing so, however, we chip away at the important human side of Christ.

It is a tenet of our faith that Jesus was fully God and fully man. Most of us have the God part figured out—we pray to him all the time—but Jesus as a man is harder to wrap our heads around. When his friend Lazarus died, he cried. When he saw the moneychangers in the temple, he got angry. When he wandered in the desert, he was hungry.

Like us, Jesus saw the world, felt the ground beneath his feet, heard the birds sing, smelled the spices in the market and tasted food. Jesus was born in a particular time and place, within a particular ethnicity. This is the mystery and beauty of the Incarnation. He was the Word made flesh, and the flesh he chose was a Middle Eastern Jewish man. To deny Jesus his humanity is, in effect, to deny Christ himself. Unless we are willing to love Jesus as a brown-skinned Jewish man, can we really say we love him?

This is not a call to haul every blond-haired, blue-eyed portrait of Jesus to the dump. Some people take comfort in these paintings. I have seen images of Black Jesus in Kenya and Asian Jesus in South Korea, and they show us that he belongs to every culture. We must be careful, though, not to worship our own image. That is the textbook definition of idolatry.

I must confess, however, that while I have no problem with Asian or Black Jesus (in fact, I have a Kenyan artist’s portrayal of the Last Supper hanging in my dining room), I find Caucasian Jesus problematic because of the historical baggage associated with colonization. European features were considered beautiful and people of colour were treated as inferior.

Sadly, these messages continue to influence how many people of colour see themselves, in addition to perpetuating racism, which hurts society as a whole. It’s important to combat old colonial notions of what Christ looked like, to open the door further for those who aren’t white-skinned and blue-eyed. Portraying Jesus as Caucasian reinforces colonialism and can make him a symbol of oppression.

If the only way you can serve Jesus is by seeing him as white-skinned, I suggest that your faith is not in God, but in the power that comes with cultural Christianity. Portraying Jesus as he actually looked may help break down explicit and implicit walls of racism in the global church, and work toward a true fellowship of all believers. After all, we all serve a Middle Eastern Saviour.

Darryn Oldford is a senior soldier in Toronto.

Comment

On Saturday, February 8, 2020, Alonzo Twyne said:

On Friday, January 17, 2020, Patrick Lublink said:

I obtained a Postgraduate Certificate in Shroud Studies from an institute in Rome (2019) and have made several presentations on the Shroud in several churches including two local Salvation Army corps. I have now been invited to speak at a number of churches between now and Easter, including an Alliance Church, a Baptist Church, an Anglican Network church, a Roman Catholic church with a special invitation to Anglican churches and a military chapel. I have also been a guest presenter at an International Shroud Symposium held at Redeemer Seminary College (Christian Reformed Church) in August 2019 when I presented two peer-reviewed papers which have been accepted for publication. These two papers will also appear in the next several weeks on the oldest Shroud internet site, www.shroud.com. I have had the pleasure of sharing a meal a year ago (at Tim Horton's) with the person who was the official photographer of the Shroud in 1978 during the most intense scientific inquiry on the Shroud.

Everyone is free to accept whether the Shroud of Turin contains an actual image or not of our Lord taken at the very moment of his resurrection. I believe that if someone is interested, he or she does not need to try to guess what He looked like while He was on earth - the Shroud is a gift from God to us. In my case, I can testify that when I first saw his picture (well over 40 years ago), the Holy Spirit moved in my heart and at that moment I knew I was looking at Him.

Blessings

On Thursday, January 16, 2020, Stuart MacMillan said:

On Saturday, January 4, 2020, Josephine `Nicolosi said:

On Saturday, January 4, 2020, Melvin said:

On Saturday, January 4, 2020, Barbara McIntyre-Butler said:

On Saturday, January 4, 2020, Rob Webster said:

On Saturday, January 4, 2020, Norma trewhella said:

On Saturday, January 4, 2020, Herb Presley said:

On Saturday, January 4, 2020, Dian Wollison said:

Leave a Comment