Traditional retellings of the Joseph story in Sunday schools and churches reflect the easygoing naiveté of the Lloyd Webber-Rice musical. We gloss over Joseph’s “goody two-shoes” early days when he ratted out his brothers, taunted them with his grandiose dreams and lorded their father’s blatant favouritism over them, epitomized in the coat of many colours (see Genesis 37). Later in the story, we overlook the excruciating tests to which Joseph subjected his brothers when they appeared before him, not recognizing that their long-lost sibling had risen to power in Egypt. Joseph exacted a delicious revenge for the cruel treatment he had received from them (see Genesis 42-45). Once again we excuse this because it is inconsistent with our image of Joseph as a man blessed by God.

The way in which we skip over Joseph’s embarrassing shortcomings reflects our childlike desire for our leaders and heroes to be faultless. We want them always and only to embody untainted virtues. But a closer examination of Joseph’s story leads us to more realistic (and biblical) reflections on leadership.

Rise to Power

Joseph clearly possessed qualities that allowed him to ascend to positions of authority. The narrator attributes much of his success to the fact that the Lord was with Joseph (see Genesis 39:3). But this did not immunize him against the perils of power; it certainly did not turn Joseph into a saint.

In the house of Potiphar, Joseph became the overseer of all that Potiphar possessed. This position of responsibility brought with it the potential to satisfy baser appetites. To Joseph’s credit, when Potiphar’s wife made repeated sexual advances, he resisted. But he paid a high price for his virtue when his seductress falsely accused him of attempted rape and he was thrown into prison (see Genesis 39).

Fortunately, God’s blessing was still upon him and Joseph rose to power a second time by successfully interpreting Pharaoh’s enigmatic dreams. Joseph made sense of the confusion in the king’s mind by announcing that Egypt would experience seven years of bountiful harvests followed by seven years of famine. He then proposed a strategy to protect Egypt from famine. In response, Pharaoh appointed him to oversee Egypt’s famine emergency plan (see Genesis 41).

All of this confirms that integrity and God’s blessing are keys to ultimate success, even with apparent setbacks. But if we read further, we also find that Joseph’s rise exposed him to the ambiguous nature of power. We see this especially in the implementation of the plan to prepare for the coming famine.

Coercion and Violence

On the one hand, Joseph’s strategy to manage the predicted famine in Egypt was prudent. In the seven years of plenty, Joseph, armed with Pharaoh’s authority, gathered and stored food to compensate for the shortages that would occur during the seven years of famine (see Genesis 41). Joseph used Pharaoh’s power to mitigate the devastating effects of drought. So far, so good.

But if we look beneath the surface of the story, we see several reasons why Joseph’s plan would have required the use of force. First, taking one fifth of the land’s produce to store it for an anticipated seven years of famine (see Genesis 41:34) would be a hard sell for many Egyptians. In the ancient world, this level of taxation was excessive and would have caused significant hardship.

After Joseph had taken everything else, he took the Egyptians’ freedom.Second, not everyone in Egypt would have been convinced of the need to store vast amounts of food for some future, hypothetical famine. The human tendency to live in the present must have created significant pressure to eat now and worry about tomorrow later.

Lastly, the entire strategy to stockpile food was based on the unscientific interpretation of Pharaoh’s dreams by a Hebrew convict. How credible could that be? There would have been many “famine deniers” in the years of plenty when food was abundant.

As a result, Joseph’s strategy, though well-intentioned and necessary, required discipline and sacrifice. Joseph would have had to use Pharaoh’s power to compel farmers to hand over a portion of their crops. Those who failed to comply would have felt the sharp edge of Pharaoh’s sword. While Joseph’s exercise of power was for the greater good and led to Egypt’s survival, coercion and violence were necessary. In other words, there were victims.

Collateral Damage

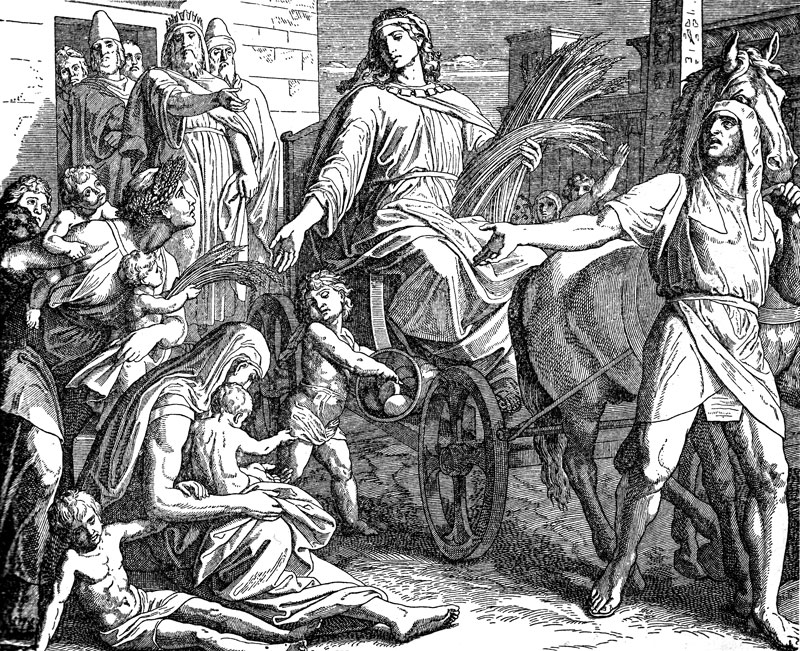

Joseph’s use of power became even more troubling once the famine struck. We read of his devastating economic strategy in Genesis 47:13-26. The food that had been taken from the Egyptian people and stored for seven years was not distributed freely—even to those who had provided it. Instead, as the famine progressed, the Egyptian people were forced to pay for food until they had handed over all of their money. Then, when their money was gone, Joseph took all of their flocks and herds as payment. When the Egyptian people had no more livestock, Joseph seized their land. Finally, after Joseph had taken everything else, he took the Egyptians’ freedom and made them Pharaoh’s slaves.

While Joseph’s strategy had saved Egypt, survival came at an extreme cost. Joseph’s “good” plan also caused great economic and personal harm. The Egyptians were enslaved even as Pharaoh’s fortunes flourished.

Hard Reality

The story of Joseph—and the stories of other great leaders in the Bible such as Moses and David—illuminates the ambiguity of power. It shows us that even when attempting to do something good, we can sometimes unwittingly do harm. Power appeals to our basest instincts, and can cause leaders great and small to succumb to temptation. Too frequently, we are blind to our own motivations. We may think we are acting in the best interest of others, when in fact we are acting out of self-interest. We may think we are being virtuous, and yet be blissfully unaware of the harm we are causing.

The frequency of failed leadership in politics and business fills today’s headlines, demonstrating that earnest appeals to honesty and integrity are not sufficient to guard against the dark side of leadership. Similar failures by Christian leaders show that it is not good enough simply to parrot pious platitudes about servant leadership or “being like Jesus.” Without confronting the deeper problems, these approaches are based more on wishful thinking than hard reality.

A Deathly Dilemma

To truly be effective, we must wrestle with the nature of power in our world. If a man like Joseph, who was guided and protected by God, was subject to these perils of power, what hope is there for us to escape them? How can we even begin to exercise power in legitimate ways? If we are blind to power’s potential to harm, is it possible that we will recklessly inflict pain and suffering precisely as we seek to do the most good? And if we are aware, will we be paralyzed into inaction? What can deliver us from this deathly dilemma? Wishful thinking won’t save us. Pious platitudes won’t save us. Avoiding the responsibility of leadership won’t save us.

Fortunately, our Christian faith offers us the resources not only to understand this “deathly dilemma,” but also to move beyond it. In next month’s Salvationist, we will explore how the gospel brings good news to leaders charged with the responsibility that comes with power.

Read Part 2 of Dr. Burke's article on Joseph: Daring to Lead.

Dr. Donald E. Burke is a professor of biblical studies at Booth University College in Winnipeg.

Feature illustration: © Sky Light Pictures/Lightstock.com

Comment

On Friday, February 2, 2018, Faye Strickland said:

Leave a Comment