In December 2023, The Salvation Army released its annual study on poverty and related socio-economic issues in Canada. It found nearly one-third of Canadians are worried about their financial future. One-quarter already find it hard to meet their basic needs. And each day I hear about young, educated, employed adults who cannot afford to live on their own.

For the first time in decades, there is a sense that the next generation will be less well off than previous generations. Those of us accustomed to a middle-class life are waking up to an injustice that already affects so many. The Salvation Army provides clear ethical direction when it comes to systemic poverty. Our Territorial Position Statement on Poverty and Economic Justice states: “The measure of any society is how well it cares for its weakest [poorest] citizens.” As Salvationists and as a Salvation Army, are there changes we ought to consider when it comes to caring well for others in our economy?

DAILY BREAD

Jesus healed, fed and taught. I don’t remember him making anyone wealthy. In fact, he said, “You always have the poor with you” (Mark 14:7 NRSVUE). This was not a statement of complacency. Nor was it directed only at those within earshot. It was an indictment on all human societies: Never has there been a society without poverty.

Jesus’ life looked much different than ours. He did not have a home (see Matthew 8:20). He relied on the hospitality of others and grainfields and fig trees for food. He was comfortable engaging anyone who came to him but spent most of his time with the down and out.

Jesus was born into a people taught to depend on God. Israel’s earliest experiences include being sustained by a daily rain of meals (see Exodus 6 and Numbers 11). Apart from the Sabbath, they were not to store food for the future, trusting God would continue to provide. This dependence carries through to Jesus’ prayer for daily bread and his miracle of feeding thousands with just a few loaves.

Dependence on God is evidenced in his teachings, too. Jesus told the richest that they can abide by the law all they want, but if they do not replace their financial security with the treasure of heaven, they are incapable of following Jesus (see Luke 18:22). The message to his closest followers was the same: “None of you can become my disciple if you do not give up all your possessions” (Luke 14:33 NRSVUE).

The Apostle Paul agrees, observing that money “is so uncertain” while God “richly provides us with everything for our enjoyment” (1 Timothy 6:17).

This is so different from the way we live, isn’t it? You and I are accustomed to saving. We save for houses, cars and rainy days. We save for retirement and the well-being of our children. Saving is one way we participate in our economy. Now, as Christians, we certainly sing and pray about relying only on God. But behind our songs and prayers is a desire for and expectation of financial stability. I think that’s natural. And I find it hard to believe that God wants us to live in a perpetual state of precarity.

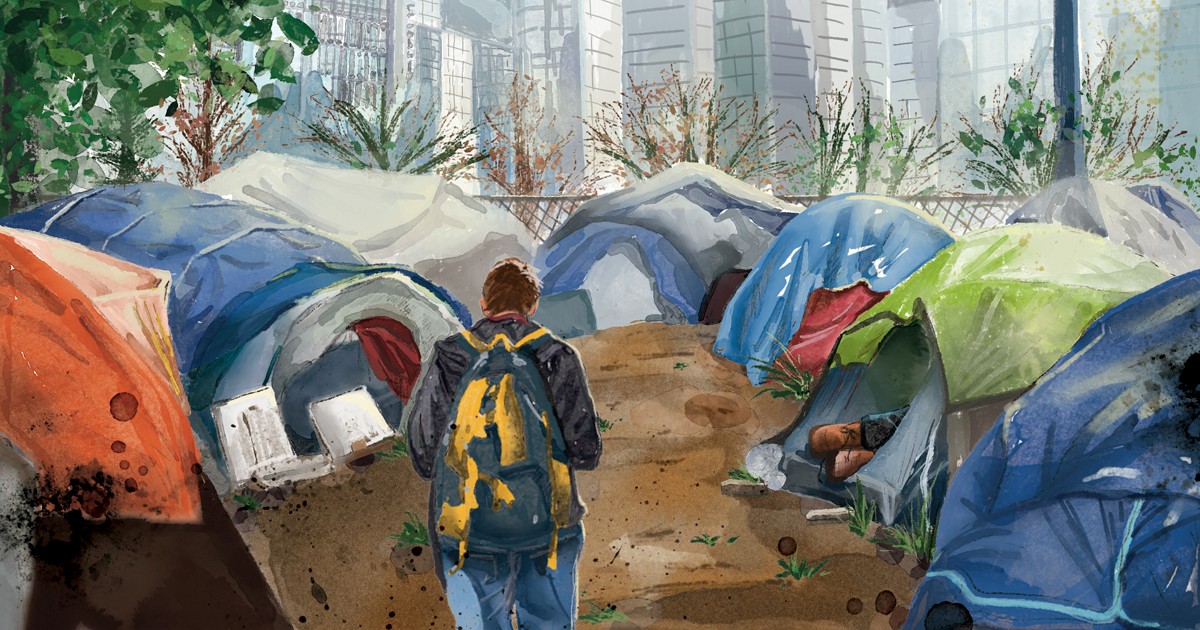

Yet Jesus said the poor, who are always with us, are blessed (see Luke 6:20). The Book of Ecclesiastes puts it this way: worries about wealth keep the rich up at night, and money holds them at arm’s length from lower socio-economic classes. But the vulnerable who exhaust themselves with labour sleep soundly (see Ecclesiastes 5:12). They know the wisdom of being community: when one person falls down, someone else will be there to lift her up (see Ecclesiastes 4:9- 10). It’s a witness I see each day as I pass by the communities we call tent cities.

JUBILEE

Jesus was also born into a people taught to practise jubilee, the cyclical return of property to its original owner (see Leviticus 25). It’s unlikely that jubilee was practised. But it would have prevented one generation from inheriting the debt of the previous generation. Jubilee signified the value of socio-economic equity—something that would have been unique for any nation. So, when Jesus declares in the temple that he has enacted God’s divine jubilee, he reveals the purpose behind the calling to give up wealth and possessions: to bring good news to the poor (see Luke 4:19).

In Acts, the earliest Christian church carried out a life of good news by abolishing private ownership of land, houses and possessions. The funds gained were “distributed to each as any had need” (Acts 4:32-35 NRSVUE). There was not a poor person among them. But as it was for jubilee, this new Christian economy was short-lived, if at all practised. Too many people became corrupt, motivated in part by a desire to evade poverty should anything go wrong.

Jesus would have named their sin a lack of love. In a parable about economic justice, he describes two individuals who owe money to the same person—someone who forgives both debts, large and small, expecting nothing in return (see Luke 7:36-50). This, Jesus observes, is loving one’s neighbour as oneself. Such love expects nothing in return, but it can elicit loving responses from the beloved.

Paul agrees that mutual giving is mutual love (see 2 Corinthians 8:8-24).

Debt is also central to Jesus’ prayer: forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors (see Matthew 6:12). Surely, I’m not the only person who limits the Lord’s Prayer to its spiritual meaning. After all, it’s easier for me to forgive another’s sins than another’s debts. I participate in an economy that functions on debts, loans and interest.

Into my reluctance, Jesus brings two truths. First, spiritual health and socioeconomic health are not estranged from each other. The economy is no object lesson. Consider that in Matthew’s version, Jesus bookends his prayer with a pair of teachings on money—one, a lesson on giving humbly, and the other, a discourse on forgiving debt (see Matthew 6). Likewise, in Luke’s version, Jesus follows up his prayer with a series of woes to be suffered by the rich (see Luke 6). They have already received the extent of their reward.

He goes on to identify love as a generous—we might say wasteful!—gift. Jesus’ wasteful love is later lived out when he invites himself to the home of Zacchaeus, a thieving tax collector who repays four times what he owes to those from whom he has stolen (see Luke 19). If even Zaccheaus can be wasteful in love, can’t we?

The second truth is that Jesus does not pray only on his account. He brings his community into the prayer, making a shared petition to God: give us this day our daily bread. Combine this with forgiving debt and we see a prayer that points to community. If we have more bread than we need for the day, who else are we feeding?

Wasteful love can seem irresponsible—even unjust. The woman who washed Jesus’ feet with expensive perfume could have sold it and fed many mouths (see Mark 14:5). Yet this wasteful woman is praised by Jesus. In a world where the poor are always with us, her faith is strong enough to depend on God, and her love is strong enough to give wastefully to others.

HOW THEN SHALL WE LIVE?

We straddle a fine line living in the economy but not of the economy. When it comes to financial security, what God wants from us as individuals and as community is both clear and complex. We need to explore it.

Wherever that exploration leads us, we cannot deny that God loves us all. Even so, God has turned the tables. Divine justice will reach people who suffer poverty long before it comes close to people like me, who struggle against parting with a middle-class life.

To read the 2023 Canadian Poverty and Socioeconomic Analysis, visit salvationist.ca/2023povertyreport.

DR. AIMEE PATTERSON is a Christian ethics consultant at The Salvation Army Ethics Centre in Winnipeg

Illustration: Rivonny Luchas

This story is from:

Thank you for this Dr. Patterson.

700 years before Jesus, the prophet Isaiah said, "What sorrow for you who buy up house after house and field after field, until everyone is evicted and you live alone in the land." (Isaiah 5:8 NLT) As this behaviour persists 2700 years later, it is safe to say (once again) that Jesus was right. I agree that Jesus was not merely being conciliatory when He said, “You always have the poor with you." When you said "living in the economy but not of the economy," a paraphrase of an Aldous Huxley came mind: our perfect adjustment to the homelessness and poverty--whatever it is about our system that allows for this--all around us is a measure of our hardheartedness.