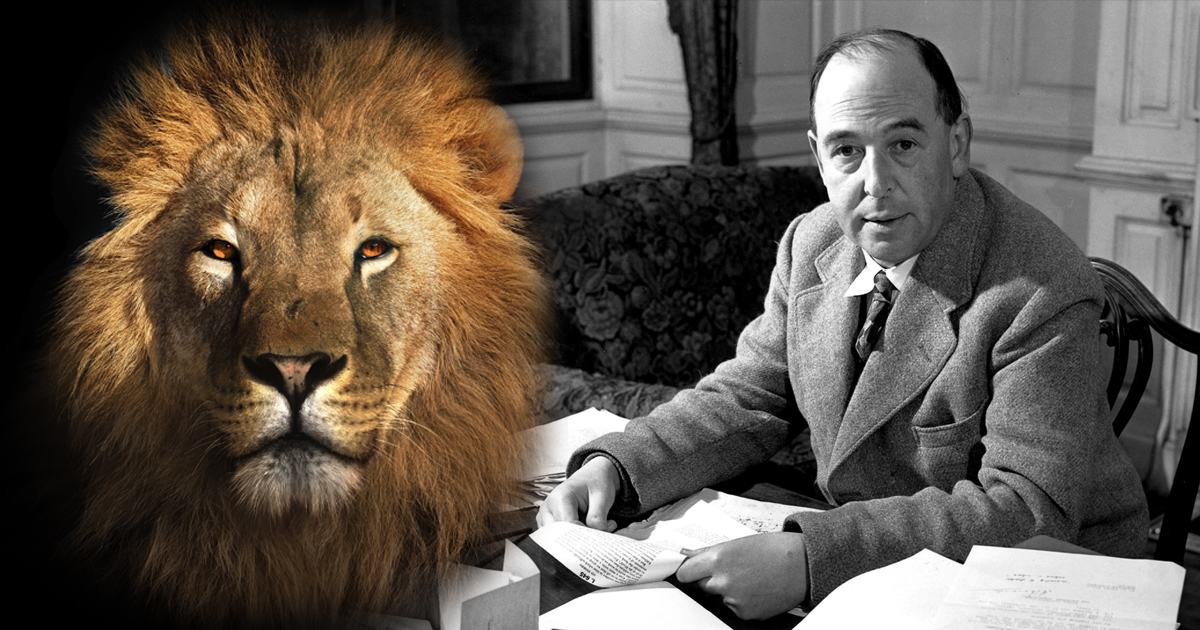

I’ve held a deep fondness for C.S. Lewis’ beloved series, The Chronicles of Narnia, since I was a child. I owe my aunt a big thank-you for gifting me these cherished books, which now occupy a place of honour in my office. Over the years, I’ve read and reread them countless times, each time filling me with a sense of wonder and delight. However, as I honed my critical reading skills and learned about systemic power dynamics, my once-naive love for Narnia evolved into a more complex and nuanced relationship with Lewis’ fantastical tales.

Reading with adult eyes, I saw how heavy-handed the allegorical nature of the stories could be. The characters, especially in the later novels, felt exaggerated to the point of parody. Lewis’ class assumptions and the conspicuous absence of Susan and Lucy from battle scenes also began to gnaw at my conscience, but I still loved the books and reread them at least once ayear.

But the most unsettling aspect of the series revealed itself a few years ago, when I was teaching a class on C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, author of The Lord of the Rings—both members of the Inklings, a literary discussion group at the University of Oxford during the 1930s.

The majority of my students, many of whom were Salvation Army officers, were, like me, introduced to Lewis’ novels during childhood. Some had even passed on the torch to their own children and grandchildren, perpetuating the timeless appeal of Narnia. Yet, there was one student who stood apart. They had enrolled in the class as an elective and had no prior exposure to Narnia or Middle-earth. During our discussion of Lewis’ The Horse and His Boy, this student bravely voiced, “Well, I found this one a little bit racist.”

Predictably, the other students leaped to Lewis’ defence, offering up well-intentioned but well-worn excuses: “He lived in a different era with different attitudes about race and other cultures.” I, too, a lifelong fan, found myself echoing this familiar refrain: “We need to read this in its historical context.”

However, after class, I couldn’t shake the feeling that I needed to delve deeper into the text. I returned to the pages of Narnia, scrutinizing the portrayals of race with fresh eyes. And there, in Lewis’ depiction of the Calormene, the inhabitants of a southern land called Calormen, I saw what that student had seen. Lewis had unwittingly embraced stereotypes of Middle Eastern culture to construct his Calormene characters. Their clothing, customs and culture all served to emphasize their “otherness” in stark contrast to the noble and civilized Narnians.

This was a classic example of Orientalism, as elucidated by cultural theorist Edward Said. By portraying the Calormene as the “other,” Lewis had effectively cast them as the villains of the story. They were labelled as “bad” simply because they were different. In a startling twist, the Calormene slave Shasta, the hero of The Horse and His Boy, was unveiled to be none other than Prince Cor from Archenland—Narnia’s equally cultured neighbour—who had been abducted as a child. Astonishingly, he was not Calormene at all.

The implications were profound: the character we most closely identified with, the one we could relate to, could not possibly hail from an exotic and savage land; he must belong to a place like Narnia. The entire narrative was meticulously designed to guide Shasta away from the “negative” influences of Calormen, steering him toward embracing his true identity as a noble Archenlander. The underlying bias in Lewis’ work became all too evident: the only redeemable Calormene was not truly a Calormene. He couldn’t be. The mere fact that we identified with him was proof that he could not be classified as an “other.”

I found myself grappling with the harsh reality that a beloved literary work, something I cherished deeply, propagated a perspective on race with which I fundamentally disagree. How should we respond when something we adore contains elements that challenge our beliefs? Does being a fan necessitate that we switch off our critical faculties and objectivity? Does the fact that C.S. Lewis was a notable apologist for Christianity mean that we can’t challenge his ideas?

It’s an especially important conversation to have at this moment. As I write this, we have just marked the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, and I struggle to reconcile the church’s actions and crimes. I watch some Christians dismiss these atrocities as “something from the past and another time.”

Our natural inclination is often to staunchly defend our beliefs and the things we hold dear. But in asking questions and considering the possibility that we might be wrong, we open the door to meaningful dialogue when others are curious. Frequently, we fear self-examination because acknowledging something troubling might appear as though we are undermining our entire belief system. However, if we are genuinely in pursuit of truth, we may find opportunities to engage with our beliefs that we would otherwise miss. These opportunities not only keep us humble but can strengthen our convictions rather than dismantle them. To ignore the racism or sexism present in something simply because it doesn’t align with our perspective is nothing short of arrogance.

I still hold a deep affection for the Narnia books and still return to them. Acknowledging the presence of something troubling does not necessitate abandoning the things we love. Instead, it allows us to accept them with humility, recognizing that the author may not have gotten everything right, just as we don’t have all the answers ourselves. In embracing this perspective, we become better equipped to engage in meaningful conversations, challenge our own beliefs and ensure that our cherished works continue to evolve in a world that is ever-changing.

Dr. Michael Boyce is the director of program implementation at the College for Officer Training in Toronto.

This was a great piece to reflect upon. I hate that many find questioning and contemplation a difficult pill to swallow but that’s how we grow and learn. Romans 3:10-12 NKJV As it is written: “There is none righteous, no, not one; There is none who understands; There is none who seeks after God. They have all turned aside; They have together become unprofitable; There is none who does good, no, not one.” If we know this verse to be true, why do we fight so hard to preserve reputations of the deceased and aggrandized?