Luke 15 opens with an observation that tax collectors and sinners often came to listen to Jesus teach, making the Pharisees and teachers of religious law mutter, “This man welcomes sinners and eats with them” (Luke 15:2). In their view, this was not the way a holy man should act.

Jesus responds by telling three parables. The first describes a shepherd who searches relentlessly for one lost sheep, rejoicing when it is brought home safely (see Luke 15:3-7). The second is about a woman who loses a silver coin, and searches until she finds it. Once again, great rejoicing ensues (see Luke 15:8-10). These two parables—and their emphasis on the rejoicing that takes place when someone or something lost is found—set the stage for the third, and longest, story.

In this parable, it is the younger son of a family who is lost, and whose return causes great rejoicing. Jesus tells us very little about the prodigal. We don’t know his age; we don’t know what prompted him to break free from home; we hear nothing about his mother or the family dynamic. All we know is that this younger son wants to take his inheritance and run.

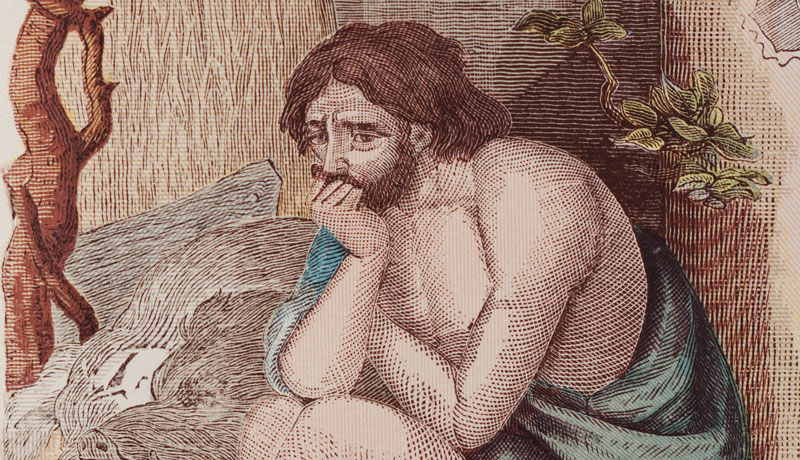

The picture becomes clearer as the story proceeds. Having received his share of the family wealth, the son departs to a faraway, exotic land. There he squanders his resources on riotous living. While he is flush with money, he seems to have many friends. But when the money runs out, his friends disappear and he is left penniless, homeless and hungry. In fact, when famine strikes the land, he is left with no other option than to work feeding pigs—a despicable prospect for a Jew, for whom pigs are unclean. In fact, he’s so hungry he wishes he could eat their food. It couldn’t get much worse. The wandering son has hit rock bottom.

Finally, he comes to his senses, realizing that even his father’s servants are treated better. They have food, respectable employment and a measure of human dignity far beyond what he has feeding these pigs.

Humbled by his experience, the prodigal ponders a return to his father’s house—not as a son, but simply as a servant. He recognizes that he is unworthy of being called his father’s son. He even rehearses the speech he will give his father, hoping he will take pity and give him a bed in the servants’ quarters and let him eat the servants’ food.

So it is that the younger son finally makes the journey home. It must have been humiliating. He who had left with his share of the family’s inheritance was coming back with nothing. The one who had commanded servants would now become a servant. That, surely, would have brought scorn and contempt his way.

Yet the story of the Prodigal Son contains hope, because he accepts responsibility for his state of affairs, acknowledging the part he played in his downfall. There was no denial, no passing the blame to someone else. He simply confessed his foolishness and sin.

This is not easy to do. It’s not even easy to use the word “sin” anymore. We have pathologies, predispositions, addictions and genetic inheritances—but we don’t often hear the language of sin. That may be a good thing at some level. But the flip side of the absence of sin in our vocabulary is that it deprives us of the opportunity to repent and receive forgiveness. Without acknowledging our sin, we are left with our brokenness— bankrupt and eating pig fodder.

The prodigal recognized and acknowledged his sin. I imagine that the prospect of meeting his father, broke and hungry, caused him considerable anxiety. What if the father were to turn him away, to reject his plea to be treated as a servant? What if he were now the one to be cut off, rather than the one who had left his family behind? What if his sin had been so great that his father would have nothing to do with him?

The only way for the prodigal to move forward was to take a chance. To risk rejection. Perhaps the son knew his father and trusted his future to him. While acknowledging that he was no longer worthy to be considered his father’s son, perhaps his father might find a way to treat him as a servant. Was this the only chance the son had for a future that didn’t involve being homeless and hungry?

But it was also possible that the father might say, “I told you so,” or “You made your bed, now lie in it.” Was it possible to go home and receive a welcome? The son’s recognition of his sin was one part of an equation, but how would the other half of the equation—the father’s response—shape the outcome?

The answer to this question will depend on the father’s response to his son’s return. That’s what we’ll explore in the next article.

Dr. Donald E. Burke is a professor of biblical studies at Booth University College in Winnipeg. This is the first in a series of three articles. Read the second article: Extravagant Love. Read the third article: The Calculus of Grace.

Illustration: © ConradFries/iStock.com

Leave a Comment