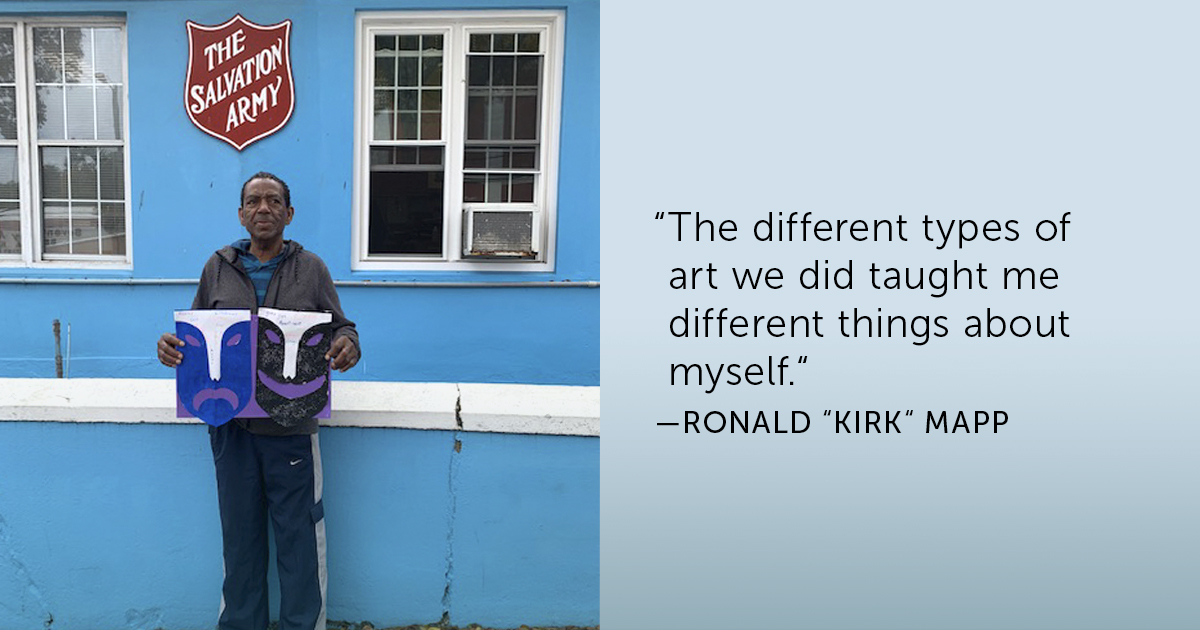

(Above) Ronald “Kirk” Mapp holds “Behind the Mask,” a project he created in the art therapy program at The Salvation Army’sHarbour Light in Hamilton, Bermuda (Photo: Sandy Butterfield)

What’s blocking your light? For Ronald “Kirk” Mapp, a resident at The Salvation Army’s Harbour Light in Hamilton, Bermuda, it was money, relationships and drugs. As part of an art therapy program, led by counsellor Elizabeth Tuzo, he wrote these words on balloons filled with paint. Outside, the group attached their balloons to a canvas and took turns throwing darts at them. When the balloons popped, it created an abstract splatter painting.

“It’s fun, it’s expressive. But at the same time, it’s a creative way to target some of the underlying issues that affect the recovery process—shame and guilt, resentments, unresolved trauma, childhood neglect,” says Tuzo. “We looked at how to identify these issues and how to manage them, so they don’t continue to show up. Then we symbolically released them.”

The balloon painting was just one of many creative projects the group has done over the past year. “The different types of art we did taught me different things about myself,” says Mapp. “A lot of them made me look at where I am and where I want to go.”

Art therapy offers residents a way to reflect on their lives, address past trauma and express their thoughts and emotions, which can help them take steps to move forward.

“To support somebody on the road to recovery,” says Tuzo, “you have to look at the whole picture.”

Changing the Narrative

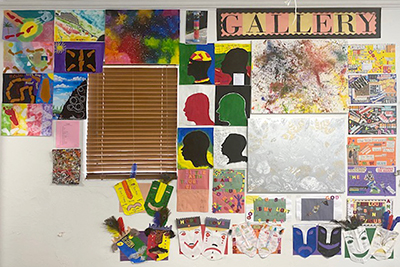

Tuzo began leading the art therapy program in August 2021, starting with a “Words to Live By” collage.

“Scripture, positive affirmations, empowering images— something they could look at on a daily basis for encouragement,” she says. “The recovery process is a journey. It’s going to have ups and downs.”

The next big project wasn’t something that could go on their gallery wall, but it made a powerful impact. Tuzo asked the residents to reflect on their legacy and how they want to be remembered, and then to design their own funeral—from the order of service to the pallbearers to writing their obituary.

“It wasn’t an easy process,” says Tuzo. “It brought up things like, ‘I’ve damaged a lot of my relationships—who will be there for me?’ It made them think about making amends and rebuilding those relationships before it’s too late.”

After meeting with residents individually for several weeks, Tuzo combined their efforts and held a formal funeral service, with a minister and a real casket. The residents acted as the choir and shared their obituaries.

“Some tears were shed,” says Tuzo. “I think the casket made it more real. When you think about the lifestyle of someone in addiction, some people in our group probably didn’t think they would live this long. But they’re still here, and they have an opportunity to change the narrative.

“So, it was uncomfortable, but it had a purpose— to think about the time they have left and what they want to do with it.”

A New Start

(Photo: Elizabeth Tuzo)

In January, Tuzo organized another creative outlet—a time capsule.

“We might have the idea of ‘new year, new me,’ but there’s always stuff that doesn’t go away just because we want it to,” says Tuzo. “We have to work through some of that old baggage.”

They began by identifying 10 things they wanted to let go of this year and discussed how long they had been carrying the weight of those burdens. Then Tuzo asked them to complete an obstacle while physically carrying a heavy weight—a bucket full of concrete, a kettle bell, a can of paint.

“I had them run up and down the stairs, do squats or try to pull someone with a rope,” she says. “We talked about what it felt like, how we can become a prisoner to something when we hold onto it.”

After decorating a container, each resident added objects representing what they wanted to let go of, and Tuzo added mementoes that reminded her of each of them. They sealed the container and buried it close to a cedar tree at the eastern end of the island.

“It was a little emotional,” says Mapp. “But at the same time, it was good, because I know that those things are behind me. I was burying my old life. Starting all over again.”

Behind the Mask

Mapp entered treatment at Harbour Light after struggling with addiction for more than 40 years.

“I was caught up in an addiction that was never ending. I woke up thinking drugs, I went to sleep thinking drugs. My whole life revolved around that,” he says. “It took me until I was 59 to decide, ‘You have to change your life.’ ”

The “Who Am I?” project helped him take a deeper look at himself. Tuzo had the men trace a silhouette of their face and answer some probing questions: What has shaped who I am today? Who am I when nobody is looking? When I look in the mirror, do I like who I see?

After Mapp presented his piece, Tuzo gently challenged him.

“It sounded like a resumé,” she says. “ ‘Ronald Kirk Mapp—I lived here, I did this, these are all my jobs.’ So, we dug deep with him to try to go beyond the surface: if we stripped all of those things away, what’s left? I remember him sitting in the chair and saying, ‘I’m not sure.’

“But that’s a great place to be, because now you get to determine, ‘Who do I want to be?’ ”

Another project that dug deep was “Behind the Mask.” Tuzo challenged clients to identify the ways in which they hide, from themselves and others, often through possessions or creating the illusion of status.

“I was projecting an image that wasn’t really me,” says Mapp. “Out in public, you’d think—this guy’s OK. But once I was home by myself, I felt sad, alone, withdrawn, angry. Outside, I was one way. But on the inside, I was hurting.”

Beautiful Path

Along with the art therapy program, the morning devotions at Harbour Light were an important part of Mapp’s journey of recovery.

“I grew up in the church, but when I was out in my addiction, I lost most of that,” he says. “But the chaplain didn’t just read the Bible—he made us understand what we were reading and how it related to our life. It helped me believe again. There is a God, and he is looking over me and guiding me.”

Today, Mapp attends church and volunteers as the audio technician. He has a job and a new bike, gifted by family, to get back and forth to work. “I have a great support system right now,” he says. “I’m keeping myself grounded, keeping myself close with my family. I don’t think any of that would have been possible if I didn’t decide to turn my life around, and it all started with Harbour Light.

“They bring you in touch with yourself and your maker, God. If you can get up every morning, praise and walk with God, you’re walking a beautiful path.”

Comment

On Monday, November 7, 2022, Stephanie Mapp said:

Leave a Comment