Lt-Col Wendy Swan is command president of women’s ministries and chair of the Moral and Social Issues Council, Hong Kong and Macau Cmd

Lt-Col Wendy Swan is command president of women’s ministries and chair of the Moral and Social Issues Council, Hong Kong and Macau Cmd

How do you define protest?

Protest is a visible, public response to an issue. There are two parts to that. One is making some form of pronouncement—saying, “Something’s not right here. This is not the way God wants the world to be.” The pronouncement calls for a halt to whatever the injustice may be. But when you take out the injustice, what are you going to replace it with? The second component of protest is an announcement—saying, “This is how God wants us to live. This is how it should be.”

How important is it for Salvationists to engage in acts of protest?

I think it’s non-negotiable. We say we are followers of Jesus, and he protested injustice wherever he found it. His love compels us to share that love in pragmatic ways. Do our protests need to look identical? Absolutely not. We live in different contexts, families, neighbourhoods—Jesus never said we had to be cookie-cutter Christians.

As Salvationists, how does our call to holiness drive our call to protest?

God calls us to be holy as he is holy. It’s not optional. When we say yes to Christ, we believe that Jesus comes to live in us by his Spirit, and that means we’re going to live differently. If Christ is in us, as we are in the world, then we become the visible, physical representation of him in the world. Even though we are not of the world, we’re called to be in the world. Jesus died for this world, not the next one.

In the 1990s, The Salvation Army established an International Spiritual Life Commission which, in its final report, issued a number of calls to action. One of them states, “We call Salvationists worldwide to restate and live out the doctrine of holiness in all its dimensions—personal, relational, social and political.” The word “political” comes from the Latin word polis, which means community. If we are a holiness people, that must be evidenced in how we respond to injustice in our community. Protesting, then, is part of our understanding of political holiness.

We often think of The Salvation Army as being “apolitical.” How does that impact our call to protest?

I think there’s been a misunderstanding around what it means to be political and apolitical. Should a Salvationist be involved in politics? Absolutely. Politics is about community. Everything is political. What we are is non-partisan, which means we do not align ourselves with a particular political party. Catherine Booth wrote about this subject in 1883, in a pamphlet called The Salvation Army in Relation to Church and State. She says, “Work with whoever you can in order to resolve the issue, and when you’ve resolved the issue, don’t align yourself with a particular political party; just carry on to the next issue.” In other words, use your networks, be intentional, but focus on the issue.

God hasn’t called the Army to be like everybody else. We were never meant to be respectable.How did Jesus protest the injustices of his time, and what can we learn from him?

In the beginning of his public ministry, we are told in Luke 4 how Jesus understands his mission: he is anointed to proclaim good news to the poor, freedom for prisoners, recovery of sight for the blind and to set the oppressed free. There’s no messing around, no soft-spoken words. There’s a lesson for us there. He was prepared to identify, in public, his mandate. I think he was saying, “When you look at my life, you need to find these things in it.” I wonder if Salvationists today are prepared to do that.

When we look at the life of Christ, we also see that Jesus protested injustice as he found it, in his everyday dealings with people. He saw situations where people were not flourishing—he saw how women and children were treated, how Israel looked at its neighbours—and he addressed them. He observed, he acted. His example challenges me. Do I really see people? And what do I do once I’ve seen them?

Interestingly, many of those who were angered by Jesus’ protests came from his own community—the religious leaders who didn’t want him to mess up the status quo. And sometimes, that’s what happens within the church. Protest makes people uncomfortable because once an injustice has been identified, you either choose to ignore it, or you choose to do something about it, but you can’t pretend you don’t know about it.

In your thesis you talk about how protest is, by its nature, sacrificial. What do you mean by that?

Sacrifice is never done on behalf of myself. Sacrifice is about self-emptying; it’s saying “no” to self so that I might say “yes” to others. Protest means saying “no” to the selfish part of me that says, “That’s your business and this is mine.” Instead, it’s giving of yourself, in a physical way, on behalf of others. We know there’s a cost involved in sacrifice. Are people going to disagree with us? Is it going to be tough? Could there be persecution? Perhaps, but I’m prepared to face that, out of my own gratitude for what Christ has done for me. And so, when we act on behalf of others by protesting, we are doing what Jesus did. He gave his life, he sacrificed all, so that we can be saved.

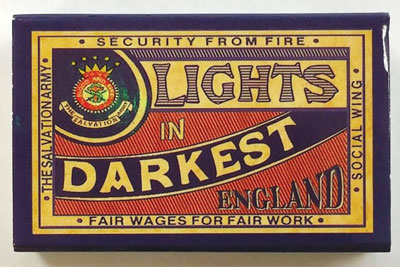

Low wages and dangerous conditions at match factories in England prompted The Salvation Army to open its own match factory in 1891, producing “Lights in Darkest England.” This act of protest forced other factories to change their practices

Low wages and dangerous conditions at match factories in England prompted The Salvation Army to open its own match factory in 1891, producing “Lights in Darkest England.” This act of protest forced other factories to change their practices

Can or should Salvationists ever engage in civil disobedience as part of an act of protest?

I’m not going to say yes or no, but I will say that when you look at the life of Jesus, on occasion, he chose to do so. In Mark 2, when Jesus and his disciples pick grain on the Sabbath, the Pharisees call them out for doing something unlawful. But Jesus is doing it to prove a point. He is saying, this law is hurting people who are already marginalized. By saying that people can’t work on the Sabbath, you’re making it harder, if not impossible, for these people to eat, and you’re marginalizing them even more. And that’s wrong. By breaking the law, Jesus was physically, visibly drawing attention to this issue. How else would people have paid attention if he hadn’t done it that way?

Is the Army too “respectable” or “safe” today? Does that sometimes prevent us from protesting and seeking societal reform?

Absolutely, there’s a danger in being respectable. God hasn’t called the Army to be like everybody else. We were never meant to be respectable. Over the course of its history, the Army has done some fabulous work—people have given sacrificially, all across the globe. The danger comes when we begin to believe our own hype; when we begin to believe that we really are wonderful. I’m not saying that’s happened, but the danger is always there. And last time I checked, the job is not done—we are perhaps more aware of injustices now than ever. So if being respectable means that we no longer seek people on the margins; if being respectable means that we act in such a way so that we don’t upset anybody—we’re in trouble.

Protest makes people uncomfortable because once an injustice has been identified, you either choose to ignore it, or you choose to do something about it, but you can’t pretend you don’t know about it.I was in a conversation one time, in an ecumenical setting, and someone commented that “Christians should never go to a pub.” I said, “Why not?” and they said, “Because it’s that kind of place.” I countered, “Well, wouldn’t that be a good place to be to have conversations with people?” That interaction reminded me that there’s a danger in becoming so sanitized that we pull ourselves out of the world. We don’t want to be “tainted.” But when you read Scripture, Jesus continually sent his disciples out into the community to meet people where they were.

How should Salvationists respond to people, or even governments, who oppose our protests?

Richard Mouw, former president of Fuller Theological Seminary, speaks of “convicted civility.” It means maintaining your conviction while still nurturing a spirit that is kind. I like that because when people push back, our natural response is to get angry and offensive, and I don’t believe that approach accomplishes much. You’ve got to keep the communication channels open and believe in creative possibilities. Two steps forward, with one step back, is still one step forward.

How can we fight back against the pessimism which says “nothing will change, so why bother”?

One practical consideration that can guide us when we protest is the idea of approximate justice. If you hold to an all or nothing approach, it is easy to become discouraged. Approximate justice says that some justice is better than no justice. Making the world a better place is not our mission, it’s God’s mission, and he calls his people to join him. It may be a hard slog but it’s going to work, and in the end, we win.

The act of protesting can transform the world. How can it also transform us?

It gives us a pragmatic, experiential, invigorating understanding of what holiness is. It’s the reality of John 10:10, where Christ says, “I have come that they may have life, and have it to the full.” I know, intellectually, that the Spirit is working in me, but when you place yourself in the gap, in whatever way that you protest, you realize that this is what it means to be a believer. It’s living right and righting wrongs. In Chinese, we have three characters for The Salvation Army, and the literal translation is, “Save the World Army.” That’s what protesting is—it’s participating in saving the world!

Ultimately, we know when we’re supposed to do something. We just do. We get the nudging, and then we have to choose: Are we going to do something or not?

*Photo (top): Australian Salvation Army officer Cpt Craig Farrell is arrested after participating in a Love Makes a Way protest in October 2014. With permission from territorial headquarters, Cpt Farrell joined the group’s peaceful occupation of the offices of Richard Marles, a member of the Australian parliament, to protest the country’s treatment of refugees (Photo credit: Love Makes a Way)

I think each one needs to be free choosing which path to fight for injustice .. there is not just one way! Jesus is the Way!